A mix-and-match approach to COVID-19 vaccines could provide logistical and immunological benefits

- Written by Maureen Ferran, Associate Professor of Biology, Rochester Institute of Technology

While it’s now pretty easy to get a COVID-19 shot in most places in the U.S., the vaccine rollout in other parts of the world has been slow or inconsistent due to shortages, uneven access[1] and concerns about safety[2].

Researchers hope that a mix-and-match approach to COVID-19 vaccines will help alleviate these issues and create more flexibility in the immunization regimens available to people.

Around the world, different pharmaceutical companies have taken different approaches to developing vaccines. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna created mRNA vaccines[3]. Oxford-AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson went with what are called viral vectors[4]. The Novavax COVID-19 vaccine is protein-based[5].

So mixing vaccines could mean more than just switching manufacturers – like from Pfizer for dose one to Moderna for dose two. You might be tapping into a different way to stimulate your immune response[6] if you opt for a first dose of AstraZeneca and a second dose of Moderna.

The most obvious benefits of treating various brands and kinds of COVID-19 vaccine as interchangeable are logistical[7] – people can get whatever shot is available without worry. By speeding up the global vaccination rollout, mixing and matching vaccines could help end this pandemic[8]. Researchers also hope combining different vaccines will trigger a more robust, longer-lasting immune response[9] compared to receiving both doses of a single vaccine. This approach may better protect people[10] from emerging variants.

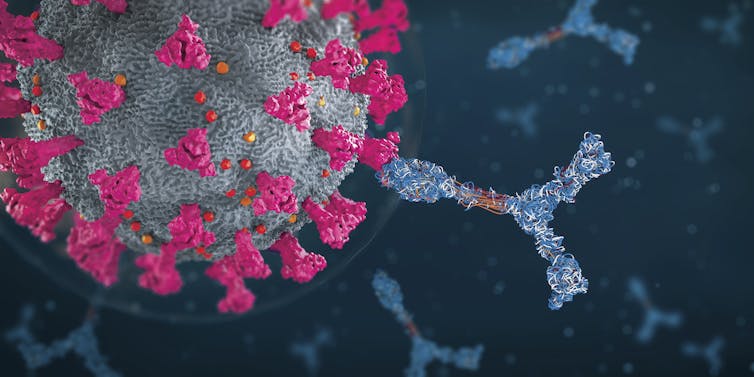

After vaccination, your body makes antibodies (blue in this illustration) that will hunt for coronavirus proteins (pink).

Christoph Burgstedt/Science Photo Library via Getty Images[11]

After vaccination, your body makes antibodies (blue in this illustration) that will hunt for coronavirus proteins (pink).

Christoph Burgstedt/Science Photo Library via Getty Images[11]

Biological effects of a mix-and-match approach

Scientists suspect there are a few ways that receiving two different COVID-19 vaccines may result in a stronger immune response[12].

Each company used slightly different regions of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein[13] in their formulations. It’s the virus’s spike protein that your immune system responds to, so exposure to different portions of the spike protein should mean your body will make an array of corresponding antibodies that can fend off future infection. The range of antibodies should then provide better protection and increase the likelihood that you’ll be protected from variants with changes in the spike protein.

And different vaccine technologies activate unique aspects of the immune system thanks to how they present their portion of the spike protein.

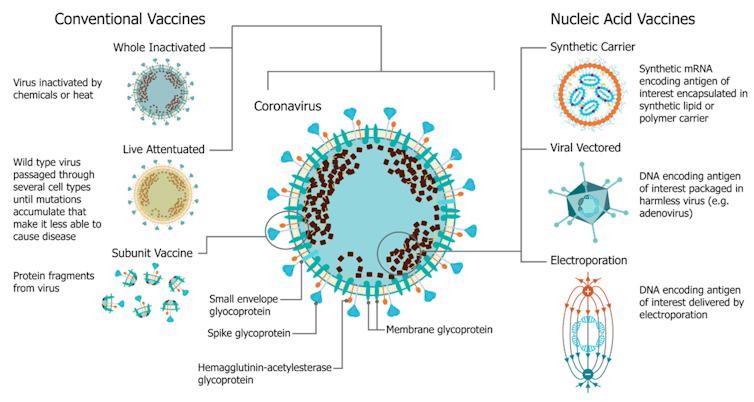

Researchers can build vaccines based on a number of what they call platforms – different technological ways to safely introduce your immune system to the targeted virus.

Blakney AK, Ip S, Geall AJ. An Update on Self-Amplifying mRNA Vaccine Development. Vaccines. 2021; 9(2):97., CC BY[14][15]

Researchers can build vaccines based on a number of what they call platforms – different technological ways to safely introduce your immune system to the targeted virus.

Blakney AK, Ip S, Geall AJ. An Update on Self-Amplifying mRNA Vaccine Development. Vaccines. 2021; 9(2):97., CC BY[14][15]

The Pfizer[16] and Moderna[17] vaccines are composed of a small snippet of mRNA, genetic material that contains the recipe to make a region of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Wrapped up in a fat coat, the mRNA slips into a vaccinated person’s cells where it directs production of the viral protein. The person’s immune system then recognizes the foreign spike protein and produces antibodies against it.

Several other COVID-19 vaccines rely on a viral vector[18]. In these cases, researchers modified an adenovirus that usually causes the common cold[19] to deliver the DNA instructions for producing a portion of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The modified virus is safe because it can’t replicate in people. Along with J&J[20] and AstraZeneca’s[21], examples of COVID-19 viral vector vaccines in use globally include Russia’s Sputnik V[22]and the CanSino Biologics vaccine[23].

Your immune system can develop an immune response to the viral vector vaccine itself[24], which could reduce the vaccine’s effectiveness against the coronavirus. Experts hope that combining vaccine platforms, for example using an mRNA-based vaccine or one that includes a different viral vector for the second dose[25], could reduce that risk[26].

Investigating combos’ safety and effectiveness

Around the world, studies are underway in animals[27] and people[28] to investigate[29] the safety, types of immune response generated and how long immunity lasts when one person receives two different COVID-19 vaccines.

Results from a Spanish trial[30] of more than 600 people indicated that vaccination with both the viral-vector AstraZeneca and mRNA-based Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines triggers a robust immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Preliminary results from a German study[31] that has not yet been peer-reviewed found that getting the AstraZeneca vaccine first followed by the Pfizer vaccine resulted in production of more protective antibodies and provided better protection against variants of concern compared to two AstraZeneca doses.

The Com-COV study[32] in the U.K. is also investigating the safety and effectiveness of giving patients a combination of the AstraZeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech shots. Preliminary findings[33] indicate that people who got one shot of each type were more likely to report mild to moderate side effects than those who received two doses of the same vaccine. Final results of this study, including the effectiveness of this approach, are expected in June 2021. The expanded Com-CoV2 study[34] is testing other combinations of COVID-19 vaccines, namely from Moderna’s mRNA platform and Novavax’s protein platform.

Mixing might be important as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

Thomas Kienzle/AFP via Getty Images[35]

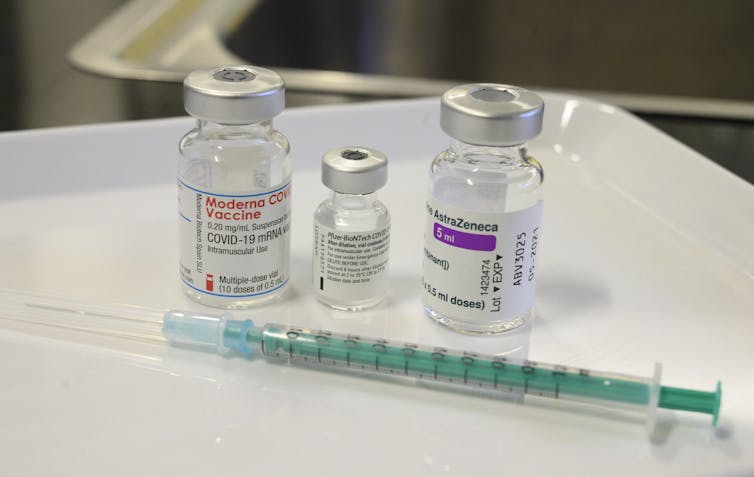

Mixing might be important as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

Thomas Kienzle/AFP via Getty Images[35]

Combos could be a good anti-variant strategy

Emerging coronavirus variants are one of the most intriguing reasons[36] to consider mixing vaccines. Administering vaccines that target different variants would provide broad collective immunity and limit emergence of new possibly more dangerous strains.

It’s possible that people who are currently fully vaccinated will need a third shot to address genetic differences in new variants. Changing platforms for this booster shot – for instance, if your first round was viral-vector based, switching to mRNA or one that is protein-based – could help bolster your immune response.

Flu vaccines routinely protect against multiple strains of the influenza virus[37] – but these are usually manufactured by the same company. In the future, this approach could lead to vaccines that contain multiple regions of SARS-CoV-2 to protect against several variants, or regions of both the coronavirus and influenza proteins, protecting against both viruses in a single shot.

What’s allowed so far

For now, though, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. allows the mixing of the mRNA-based Pfizer and Moderna shots only in “exceptional situations[38],” such as limited vaccine supply or if a patient doesn’t know which vaccine they originally received.

Canada’s public health agency recently approved the mixing of different COVID-19 vaccines[39] if limited supply prevents someone from getting their second dose of the same vaccine, or if someone is apprehensive about a second dose of AstraZeneca[40] due to publicized side effects.

EU countries are so far awaiting further study results[41] before allowing mixing vaccine doses.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter[42].]

References

- ^ shortages, uneven access (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ concerns about safety (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ mRNA vaccines (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ viral vectors (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ protein-based (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ different way to stimulate your immune response (www.nature.com)

- ^ logistical (health-desk.org)

- ^ mixing and matching vaccines could help end this pandemic (www.cbc.ca)

- ^ more robust, longer-lasting immune response (www.npr.org)

- ^ better protect people (www.advisory.com)

- ^ Christoph Burgstedt/Science Photo Library via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ may result in a stronger immune response (www.nature.com)

- ^ different regions of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (viralvector.design.blog)

- ^ Blakney AK, Ip S, Geall AJ. An Update on Self-Amplifying mRNA Vaccine Development. Vaccines. 2021; 9(2):97. (www.mdpi.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Pfizer (www.pfizer.com)

- ^ Moderna (www.modernatx.com)

- ^ viral vector (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ modified an adenovirus that usually causes the common cold (theconversation.com)

- ^ J&J (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ AstraZeneca’s (theconversation.com)

- ^ Russia’s Sputnik V (sputnikvaccine.com)

- ^ CanSino Biologics vaccine (www.thelancet.com)

- ^ immune response to the viral vector vaccine itself (www.reuters.com)

- ^ for the second dose (sputnikvaccine.com)

- ^ could reduce that risk (www.gavi.org)

- ^ in animals (www.advisory.com)

- ^ and people (www.reuters.com)

- ^ to investigate (udaipurtimes.com)

- ^ Results from a Spanish trial (www.nature.com)

- ^ German study (www.news-medical.net)

- ^ The Com-COV study (comcovstudy.org.uk)

- ^ Preliminary findings (doi.org)

- ^ expanded Com-CoV2 study (comcovstudy.org.uk)

- ^ Thomas Kienzle/AFP via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ most intriguing reasons (www.nih.gov)

- ^ multiple strains of the influenza virus (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ exceptional situations (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ mixing of different COVID-19 vaccines (www.npr.org)

- ^ if someone is apprehensive about a second dose of AstraZeneca (www.ctvnews.ca)

- ^ awaiting further study results (www.reuters.com)

- ^ You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Maureen Ferran, Associate Professor of Biology, Rochester Institute of Technology