New technologies claiming to copy human milk reuse old marketing tactics to sell baby formula and undermine breastfeeding

- Written by Cecília Tomori, Associate Professor and Director of Global Public Health and Community Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing

New products that claim to replicate mother’s milk[1] have entered the lucrative market for infant formula.

To an anthropologist and public health scholar[2] who studies breastfeeding, these claims appear to be built on old patterns of misleading scientific statements – and reveal the power of marketing to exploit gaps created by inadequate societal support for breastfeeding.

The costs of undermining breastfeeding are enormous. Globally, over 823,000 child deaths[3] could be prevented annually with appropriate breastfeeding. Additionally, 20,000 maternal deaths[4] could be averted each year worldwide from breast cancer. Poor communities of color around the world disproportionately shoulder this harm.

The rise of commercial formula

Throughout most of history and across cultures[5], communities understood that breastfeeding ensured the best chance for infants to survive and thrive. Breastfeeding continued, on average, from two to four years[6], with caregivers introducing new foods while continuing to breastfeed.

Attempts to fully replace human milk, usually with animal milk and gruels[7], were relatively rare. Such attempts were most common when mothers were ill or dead, and caregivers couldn’t locate a lactating woman. Compared with breastfeeding, replacement feeding reduced babies’ chances of survival[8].

Efforts to mimic breast milk escalated with the rise of scientific thinking and industrial capitalism[9] in Europe and the U.S. in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Mass migration to urban centers eroded community support – and poor labor conditions made breastfeeding challenging.

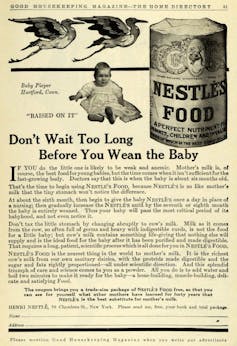

Nestlé advertisement, 1911.

Nestlé[10]

Nestlé advertisement, 1911.

Nestlé[10]

From the first commercial milk formula patented in 1865 by Justus von Liebig[11], formula-makers drew on science to gain the trust of medical providers and argue their products were as good as[12] – or even superior to – human milk. A study prepared for and published by Nestlé in 1878 asserted that mother’s milk was deficient in key nutrients[13] and infants aged 6 to 8 weeks already required supplementation – with Nestlé’s food.

Physicians often claimed to support breastfeeding while undermining it in practice with poor advice and an increasing focus on formula feeding. Pioneering American pediatrician Emmett Holt advocated his own method of making formula[14]. In his bestselling book, first published in 1894[15], Holt claimed infants could be harmed by mother’s milk that was corrupted by emotion. Holt also advised mothers to schedule brief breastfeeding sessions and limit physical contact. Such advice impeded the physiology of breastfeeding[16], which relies on frequent, responsive feedings and close contact – and contributed to growing reliance on supplementation with formula.

Physicians ultimately incorporated formula into their routine medical practices[17] and institutionalized them in hospital childbirth protocols[18].

Global spread

In the first half of the 20th century, colonial administrations spread these new “scientific” infant care norms and products around the globe. They saw bottle-feeding as a solution to infant mortality, disease and malnutrition[19] – and ultimately as an answer to labor shortages in the colonies.

In the 1950s, Nestlé used marketing techniques perfected in Europe to dramatically expand its market in Africa[20], Asia and other parts of the world[21]. The growing number of infant deaths associated with the use of these products drew international attention and ultimately led to the Nestlé boycott in 1977[22].

Nestlé’s practices were not unique among formula-makers. Growing concerns about the role of inappropriate marketing practices[23] in declining breastfeeding rates and infant illness and death led to the development of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes[24], which was adopted by the World Health Assembly 40 years ago, in 1981. The U.S. was the only nation that voted against it[25], driven by formula lobbying efforts.

Milking profits

In the 1950s through the 1970s, multiple social movements fueled increased interest in breastfeeding in the U.S.[26]. Medical experts supported these movements with a growing body of scientific research demonstrating the importance of breastfeeding for infant, child and maternal health[27]. But despite significant gains in breastfeeding[28] in some settings, like the U.S., the formula industry continues to expand[29].

Between 2005 and 2019, global formula sales increased 121%[30], led by middle-income countries. The global industry is currently valued at US$50.6 billion[31] and projected to double by 2026[32].

Infant formula is big business.

d3sign/Moment via Getty Images[33]

Infant formula is big business.

d3sign/Moment via Getty Images[33]

Formula-makers devote billions of dollars each year to marketing[34] that co-opts scientific and medical authority and undermines breastfeeding globally[35]. These marketing practices have continued to defy the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes[36].

As in the 19th century, formula marketing[37] still presents breastfeeding as an inherently problematic[38], unreliable process to which formula provides the solution.

Yet most breastfeeding challenges, like the perception of insufficient milk and the difficulties faced by lactating workers, are the product of structural and social conditions[39] that can be addressed by investing in policies[40] that provide quality perinatal care, skilled breastfeeding support, parental leave and workplace accommodations for lactating parents.

More than a food

Formula companies focus on human milk as the only important element of breastfeeding – and claim near equivalence between their product and human milk. Yet human milk is a living, life-sustaining substance with a long evolutionary history and cultural meaning[41].

Human milk is specific to our species[42]. It is dynamic and adaptive[43] – ever-changing in response to local environments. Human milk contains bioactive compounds[44] and has a unique microbiome that varies by setting and over time[45]. New technology, including the culturing of human cells[46], cannot replicate any of this.

Through complex interactions among mothers, infants and their communities, breastfeeding provides infants with optimal nutrition and protection from infectious disease[47]. Across cultures, lactation and human milk create relationships that bind families[48] and communities together.

Families need accurate information free of commercial influence to make informed decisions about breastfeeding. I believe when lactation is not possible or desired, families could benefit[49] from donor human milk[50]. Government investment in policies[51] that protect, promote and support breastfeeding remains key to creating an environment in which breastfeeding can thrive.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter[52].]

References

- ^ claim to replicate mother’s milk (www.foodnavigator-usa.com)

- ^ anthropologist and public health scholar (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Globally, over 823,000 child deaths (doi.org)

- ^ 20,000 maternal deaths (doi.org)

- ^ Throughout most of history and across cultures (www.routledge.com)

- ^ from two to four years (www.doi.org)

- ^ usually with animal milk and gruels (www.springer.com)

- ^ Compared with breastfeeding, replacement feeding reduced babies’ chances of survival (www.springer.com)

- ^ escalated with the rise of scientific thinking and industrial capitalism (uwpress.wisc.edu)

- ^ Nestlé (www.aims.org.uk)

- ^ patented in 1865 by Justus von Liebig (yalebooks.yale.edu)

- ^ argue their products were as good as (uwpress.wisc.edu)

- ^ asserted that mother’s milk was deficient in key nutrients (yalebooks.yale.edu)

- ^ his own method of making formula (uwpress.wisc.edu)

- ^ In his bestselling book, first published in 1894 (archive.org)

- ^ impeded the physiology of breastfeeding (dro.dur.ac.uk)

- ^ incorporated formula into their routine medical practices (uwpress.wisc.edu)

- ^ hospital childbirth protocols (history.wisc.edu)

- ^ solution to infant mortality, disease and malnutrition (doi.org)

- ^ dramatically expand its market in Africa (doi.org)

- ^ Asia and other parts of the world (doi.org)

- ^ Nestlé boycott in 1977 (doi.org)

- ^ role of inappropriate marketing practices (doi.org)

- ^ International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (www.who.int)

- ^ only nation that voted against it (doi.org)

- ^ increased interest in breastfeeding in the U.S. (doi.org)

- ^ scientific research demonstrating the importance of breastfeeding for infant, child and maternal health (doi.org)

- ^ significant gains in breastfeeding (doi.org)

- ^ continues to expand (doi.org)

- ^ formula sales increased 121% (doi.org)

- ^ currently valued at US$50.6 billion (doi.org)

- ^ projected to double by 2026 (www.globenewswire.com)

- ^ d3sign/Moment via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ billions of dollars each year to marketing (doi.org)

- ^ undermines breastfeeding globally (www.who.int)

- ^ continued to defy the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (www.who.int)

- ^ formula marketing (www.savethechildren.org.uk)

- ^ presents breastfeeding as an inherently problematic (doi.org)

- ^ structural and social conditions (doi.org)

- ^ investing in policies (doi.org)

- ^ long evolutionary history and cultural meaning (www.routledge.com)

- ^ specific to our species (jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu)

- ^ dynamic and adaptive (doi.org)

- ^ bioactive compounds (doi.org)

- ^ a unique microbiome that varies by setting and over time (doi.org)

- ^ the culturing of human cells (www.foodnavigator-usa.com)

- ^ optimal nutrition and protection from infectious disease (doi.org)

- ^ relationships that bind families (www.routledge.com)

- ^ families could benefit (doi.org)

- ^ donor human milk (doi.org)

- ^ Government investment in policies (doi.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Cecília Tomori, Associate Professor and Director of Global Public Health and Community Health, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing