Fireflies need dark nights for their summer light shows – here's how you can help

- Written by Avalon C.S. Owens, PhD Candidate in Biology, Tufts University

Before humans invented fire, the only things that lit up the night were the moon, the stars and bioluminescent[1] creatures – including fireflies. These ambassadors of natural wonder are soft-bodied beetles that emit “cold light,” using a biochemical reaction[2] housed in their abdominal lanterns.

Fireflies mating.

Sara Lewis, CC BY-ND[3]

Fireflies mating.

Sara Lewis, CC BY-ND[3]

Fireflies exchange bioluminescent courtship signals as a precursor to mating. In doing so, they construct spectacular light shows that inspire joy and delight in people all around the world[4]. Unfortunately, human activities threaten to extinguish these silent sparks.

In recent decades, fireflies have vanished from many places where they were once found. Like other insects, fireflies are threatened by habitat loss and pesticide use[5]. They are also uniquely vulnerable to the harmful effects of light pollution[6].

As scientists who study fireflies[7] and how they are affected by artificial light[8], we want to make sure that future generations can continue to enjoy one of nature’s greatest wonders.

A life in the dark

Fireflies evolved some 100 million years ago[9] and have blossomed into more than 2,200 species that are found on every continent except Antarctica. Here in North America, nearly 150 different species of flashing firefly light up our summer nights.

Most North American species have a two- to four-week mating season. Each evening, males and females engage in a dash of light flirtation. The males fly around, producing a species-specific pattern of flashes. Females, perched in the undergrowth, discreetly respond when they are interested with flashes of their own.

For the vast majority of evolutionary history, nighttime light sources were predictable and short-lived: The sun set, and the moon waned. But as advances in technology made it cheaper and easier for humans to light up their environment, light pollution has become a constant presence in urban, suburban and rural habitats.

Human-caused light sources – house lights, path lights, streetlights – often shine all night, year-round. Humans can use curtains to block out a neighbor’s annoying LED floodlight, but nocturnal animals aren’t so fortunate. The more we light up the night, the less space we leave for the firefly flash dance.

Synchronous fireflies, native to the U.S. Southeast, coordinate their flashes into bursts that ripple through groups of insects.Blinded by the light

We and other firefly researchers[10] have become increasingly worried about the future of these remarkable insects. More than a decade of scientific research[11] offers ample evidence that light pollution is a threat to firefly reproduction.

The fundamental problem is visibility: Fireflies use their bioluminescence to flirt in the dark. It doesn’t work so well with the lights on.

Scientists have known for some time that direct illumination from a nearby streetlight makes male fireflies flash less[12], but that is only half the story. As with most animals that engage in complex courtship rituals, female fireflies are the choosy ones – and they are watching the show with the rest of us. When a female sees a male she likes, she flashes back. He zips over, and that’s when the magic happens.

Our recent lab study[13] shows that females of a common New England firefly species are even more sensitive to direct illumination than their male counterparts. Under artificial light, males flash about half as often, while females rarely, if ever, flash back.

It may be that female fireflies are quite literally blinded by the light shining down into their eyes. Or even if they do manage to pick out a male flash pattern here and there, they might not think it worth a reply. Previous research shows that female fireflies prefer bright flashes over dim ones[14], and background light can turn an otherwise bright flash into one that is dull and unimpressive.

A female firefly signals.

Radim Schreiber/Firefly Experience, CC BY-ND[15][16]

A female firefly signals.

Radim Schreiber/Firefly Experience, CC BY-ND[15][16]

The brightness of the artificial light source makes a big difference, but its dominant color is also a factor. Fireflies don’t see blue or red light very well because they have evolved to focus in on the particular yellow-green hue that they use to communicate[17]. Amber light, which has a yellow-orange hue, is most disruptive to firefly courtship – even more so than white light – because it approaches the color of firefly bioluminescence.

Help fireflies reclaim the night

Current research supports a few simple firefly-friendly lighting guidelines[18] that can help protect both fireflies and other animals[19] that need the dark.

First, remove unnecessary light. Lights left on in the middle of the night – especially in natural habitats like backyards, parks and reserves – too often go unused by anyone. Install motion detectors, timers and shielding to ensure that light goes only where people need it, when they need it. These devices can pay for themselves[20] over the long term.

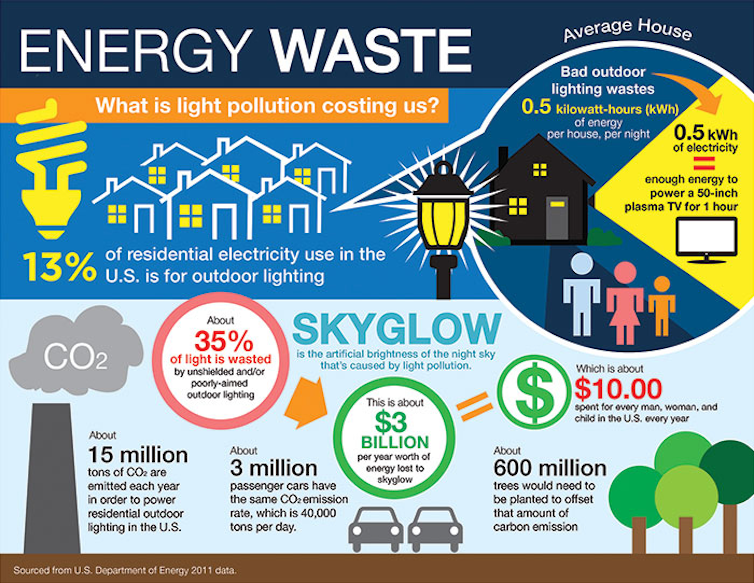

In addition to harming nocturnal wildlife, light pollution wastes energy and money.

International Dark Sky Association, CC BY-ND[21][22]

In addition to harming nocturnal wildlife, light pollution wastes energy and money.

International Dark Sky Association, CC BY-ND[21][22]

Second, keep necessary light as dim as possible. Modern LEDs tend to be much brighter than they need to be[23] for public safety. To easily dim an LED, cover it with a few sheets of paper or layers of painter’s tape. For older lighting types, which can overheat when covered, use heat-resistant cellophane or acrylic gel filters instead.

Finally, remember this: The redder the better! When buying new outdoor lights, opt for monochrome red LEDs. Some lighting manufacturers have begun to tout amber LEDs as “insect-friendly,” but they are not thinking about fireflies. And while it’s true[24] that amber light doesn’t attract as many flying insects as white light, red light attracts even fewer[25].

As with any harmful environmental pollutant, limiting how much artificial light we create will always be more effective than trying to lessen its impact. Fortunately, light pollution is instantly and completely reversible, which means that we can change things for the better for fireflies with the flip of a switch.

Fireflies give us so much, and don’t demand a lot in return – just a bit of dark night to call their own.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays[26].]

References

- ^ bioluminescent (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

- ^ a biochemical reaction (theconversation.com)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ all around the world (doi.org)

- ^ threatened by habitat loss and pesticide use (doi.org)

- ^ light pollution (www.darksky.org)

- ^ fireflies (scholar.google.com)

- ^ affected by artificial light (scholar.google.com)

- ^ 100 million years ago (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ other firefly researchers (fireflyersinternational.net)

- ^ scientific research (doi.org)

- ^ makes male fireflies flash less (dx.doi.org)

- ^ recent lab study (doi.org)

- ^ female fireflies prefer bright flashes over dim ones (doi.org)

- ^ Radim Schreiber/Firefly Experience (fireflyexperience.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ particular yellow-green hue that they use to communicate (science.sciencemag.org)

- ^ firefly-friendly lighting guidelines (xerces.org)

- ^ other animals (www.treehugger.com)

- ^ pay for themselves (www.darksky.org)

- ^ International Dark Sky Association (www.darksky.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ much brighter than they need to be (www.darksky.org)

- ^ it’s true (www.thespruce.com)

- ^ even fewer (doi.org)

- ^ Weekly on Wednesdays (theconversation.com)

Authors: Avalon C.S. Owens, PhD Candidate in Biology, Tufts University