From Rodney King to George Floyd, how video evidence can be differently interpreted in courts

- Written by Sandra Ristovska, Assistant Professor in Media Studies, University of Colorado Boulder

News media coverage of Derek Chauvin’s trial for the murder of George Floyd highlighted the role of video as a “star witness[1].” Jurors in this trial saw footage from cellphones, police body cameras, dashboard cameras and surveillance cameras. In his closing arguments, prosecuting attorney Steve Schleicher[2] even told the jurors, “Believe your eyes. What you saw, you saw.”

For the past eight years I have been studying the use of video as evidence both in international human rights courts and tribunals[3] and in state and federal courts[4] in the U.S. As a media scholar[5], I pay close attention to how people interpret video as evidence. One of the things I have found is that the argument “seeing is believing” is not as intuitive as it sounds.

‘Who do you believe?’

On March 3, 1991, a Los Angeles resident named George Holliday saw, from his apartment balcony, four Los Angeles policemen beating a Black man. He recorded the violence on video and eventually sold it to a local TV news station. This bystander footage[6] of the beating of Rodney King quickly made headlines in the U.S. and around the world.

Holliday’s video also became crucial evidence in the trial of the officers on charges of assault and excessive use of force. Lead prosecutor Terry White ended his closing arguments[7] with a final showing of the video, asking the jury: “Now who do you believe, the defendants or your own eyes?”

The jurors responded by acquitting the officers, discarding the seemingly obvious interpretation of Holliday’s video. They instead believed the skillful frame-by-frame analysis of the defense attorneys, who argued that the video was not evidence of police misconduct but of a justified response to King’s allegedly frightening actions.

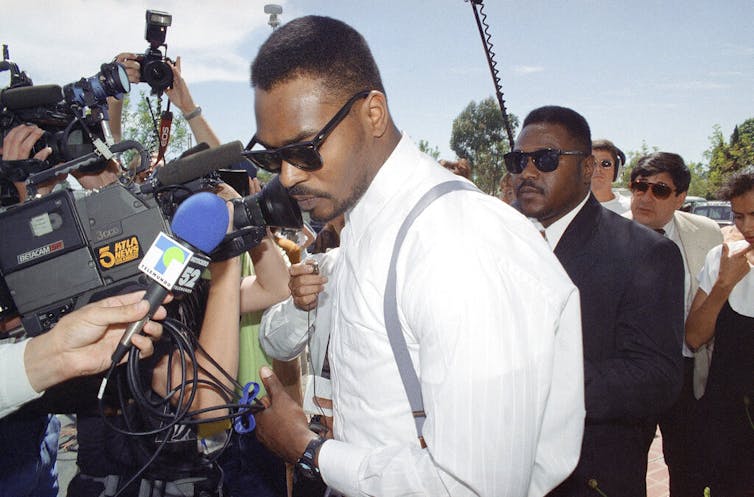

Despite the video evidence, a jury opted not to levy punitive damages on the four Los Angeles police officers who beat Rodney King (above) in March 1991.

AP Photo/Chris Martinez[8]

Despite the video evidence, a jury opted not to levy punitive damages on the four Los Angeles police officers who beat Rodney King (above) in March 1991.

AP Photo/Chris Martinez[8]

One could ask why the jurors did not believe their own eyes. It is thus important to note that seeing involves not only what the eyes see, but the experiences and ideas that the viewer brings to the image. What people see is affected by what they already know and believe, a phenomenon that art critic John Berger[9] in 1972 enduringly termed “ways of seeing”[10].

Cultural and cognitive influences

Race is one factor that shapes seeing.

In 1952, psychiatrist and political philosopher Frantz Fanon[11] famously described[12] an incident in which a white boy felt frightened just by looking at a Black man. That some might find the mere appearance of Black people threatening speaks to a long history[13] of racism that has framed people of color as less than human. In other words, seeing is influenced by power and other differences that shape the conditions of how we as humans experience the world.

Cognitive factors also have an impact on seeing. Not everyone who sees a video interprets it in the same way. Selective attention[14] is one cognitive process that accounts for different ways of seeing. For example, a psychology experiment[15] found white participants more likely to notice a Black man appearing in the middle of a video than a white man.

Camera angles affect perception as well. Another study[16] found when the camera is focused on the suspect, viewers tend to find a videotaped confession more voluntary, and thus less coercive, than when the camera is focused on the officer.

Even the associations that a video brings to mind can influence seeing. In Scott v. Harris[17], a prominent 2007 Supreme Court case involving a police car chase that left a Black driver paralyzed, video evidence was an important part of the trial and the decision. Writing for the majority[18], which sided with the police, Justice Antonin Scalia said the case was “clear from the videotape,” and that “what we see on the video more closely resembles a Hollywood-style car chase of the most frightening sort, placing police officers and innocent bystanders alike at great risk of serious injury.”

During the oral arguments, Justice Scalia even compared the dashcam footage with the famous fast and violent police car chase in the movie “The French Connection[19].”

In a lone dissenting opinion[20], Justice John Paul Stevens sided with lower court judges who disagreed with this interpretation. “This is hardly the stuff of Hollywood,” Justice Stevens wrote. The video “surely does not provide a principled basis for depriving the respondent of his right to have a jury evaluate the question whether the police officers’ decision to use deadly force to bring the chase to an end was reasonable.”

[3 media outlets, 1 religion newsletter. Get stories from The Conversation, AP and RNS.[21]]

This case serves as another reminder that seeing is not intuitive. Courts may use video evidence differently, even within the life span of the same case.

Safeguards for rigorous visual interpretation

Video is neither a transparent nor an opaque form of evidence but an opportunity to ask important questions, just as with any other type of evidence.

Some of these questions cannot be answered by any one video on its own. Not all court cases feature multiple videos that authenticate one another, but Derek Chauvin’s trial relied on numerous videos[22] from different cameras and locations, each providing a distinct perspective on the crime scene. These videos corroborated one another, helping reconstruct what led to George Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020.

The trial also featured 37 witnesses for the prosecution. Among them was Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo[23], who testified that Chauvin’s actions violated relevant department policies. For the jury, the multiple videos and witness testimonies proved the murder charges beyond a reasonable doubt.

Bystander, bodycam and dashcam videos of policing can be powerful forms of evidence that help jurors bear witness to an event from the complicated scenes of its occurrence. Yet judges, attorneys and jurors may see and treat video in varied ways that can lead to inconsistent renderings of justice. U.S. courts thus need safeguards to ensure that video evidence is rigorously assessed during trial.

References

- ^ star witness (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ Steve Schleicher (www.youtube.com)

- ^ international human rights courts and tribunals (mitpress.mit.edu)

- ^ state and federal courts (doi.org)

- ^ media scholar (www.colorado.edu)

- ^ This bystander footage (www.history.com)

- ^ ended his closing arguments (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Chris Martinez (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ John Berger (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ “ways of seeing” (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ Frantz Fanon (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ famously described (groveatlantic.com)

- ^ a long history (www.routledge.com)

- ^ Selective attention (www.theinvisiblegorilla.com)

- ^ a psychology experiment (doi.org)

- ^ Another study (doi.org)

- ^ Scott v. Harris (supreme.justia.com)

- ^ Writing for the majority (supreme.justia.com)

- ^ The French Connection (www.imdb.com)

- ^ lone dissenting opinion (supreme.justia.com)

- ^ Get stories from The Conversation, AP and RNS. (theconversation.com)

- ^ numerous videos (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ Medaria Arradondo (www.youtube.com)

Authors: Sandra Ristovska, Assistant Professor in Media Studies, University of Colorado Boulder