Georgia voter suppression efforts may not change election results much

- Written by Bernard Tamas, Associate Professor of Political Science, Valdosta State University

There has been understandable outrage[1] and widespread criticism[2] of the new voting laws in Georgia[3] – and of similar efforts in other states[4]. These laws would likely make voting more difficult[5], including by reducing options for voting and making it harder to use an absentee ballot. My research[6] indicates, however, that such measures may not change election results much, if at all.

Most U.S. voting districts at both the congressional and state legislative levels are safely controlled by one party or the other. Laws that slightly reduce the number of potential voters are unlikely to shift power in Congress and state legislatures significantly.

In addition, my analysis has found that Republican-led partisan gerrymandering efforts actually work against voter suppression measures[7], by packing Democratic voters into relatively few districts that the party wins easily. That means Democrats have fewer competitive seats to potentially lose, even when some of their supporters are kept from the polls.

History of voter suppression

Voting access laws have changed considerably since the end of the Jim Crow era in the mid-20th century. The American public then was far more willing to accept overt voter suppression requirements, like poll taxes and literacy tests, which were widely used in Southern states to keep African Americans from voting[8].

But the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s undermined public support for those laws[9]. As a result, current state governments that want to reduce voter access to the polls have to find less obvious methods to do so.

When they devise methods to limit voting now, state governments have to claim that such measures will protect voting integrity[10] or save taxpayer money[11]. This ends up limiting the aggressiveness of voter suppression measures that states can enact, which in turn reduces their potential effectiveness.

Georgia’s new laws don’t really affect who is eligible to vote, but they do make voting more difficult for poorer populations[12] and those living in urban areas. Making access harder may not, however, be enough to stop people from voting. There is significant political science research showing that changes to voting options and absentee ballot use don’t meaningfully affect voter turnout[13].

For instance, permitting most citizens to vote by absentee ballot does not give either party an electoral advantage[14]. Such findings suggest that restricting voting by mail won’t help one party over the other, either.

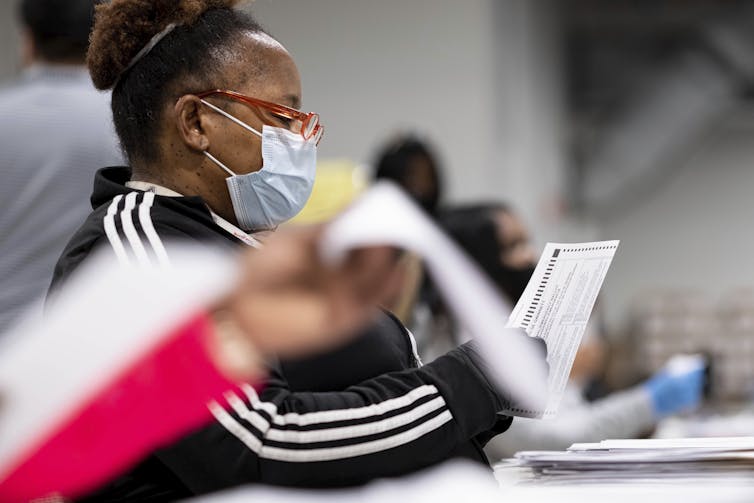

Election workers in Georgia handled large amounts of mail-in ballots during the 2020 presidential election and the January 2021 U.S. Senate runoff races.

AP Photo/Ben Gray[15]

Election workers in Georgia handled large amounts of mail-in ballots during the 2020 presidential election and the January 2021 U.S. Senate runoff races.

AP Photo/Ben Gray[15]

Election margins in Georgia

In situations where many districts are closely divided, a small amount of voter suppression can change the balance of power. But if most districts are clearly dominated by one party or the other, then flipping its control would require much more effort to reduce voter turnout.

At this point in American history, most election outcomes are predictable. Partially as a result of gerrymandering, most districts are reliably won by a large percentage of the vote. In 2020, for example, Georgia Democrats won close elections in just one out of 56 state Senate races and seven out of 180 state House races[16].

This is where my research has identified the opposing impacts of gerrymandering and voter suppression[17]. In Georgia, both congressional and state legislative elections are impacted by gerrymandering[18].

In 2020, nearly two-thirds of the Democratic seats in the Georgia General Assembly and U.S. House of Representatives were won in races where Republicans didn’t even field a candidate. Just 1% of the Democratic wins were by close margins of less than 2 percentage points.

By the 2022 midterm elections, state governments will redraw all legislative district lines. These new districts will almost certainly be equally or more gerrymandered[19] than they are today. Redistricting is therefore not likely to significantly reduce existing vote margins.

Unlike legislative elections, statewide races in Georgia have become far closer in recent years. In the 2018 gubernatorial election[20], for instance, Republican Brian Kemp beat Democrat Stacey Abrams by just over 1% of the vote. During the 2021 U.S. Senate runoffs[21], Democrat Jon Ossoff beat Republican David Perdue by just over 1% of the vote and Democrat Raphael Warnock beat Republican Kelly Loeffler by 2%.

However, limiting absentee voting and increasing wait times at the polls may not be enough to shave off even a few percentage points of Democratic voters across all of Georgia.

Georgia U.S. Senators Raphael Warnock, left, and Jon Ossoff, both Democrats, were elected in runoff elections in January 2021.

AP Photo/Alex Brandon[22]

Georgia U.S. Senators Raphael Warnock, left, and Jon Ossoff, both Democrats, were elected in runoff elections in January 2021.

AP Photo/Alex Brandon[22]

What’s at stake

The real problem Georgia Republicans are facing is not that more Georgia Democrats are voting. Rather, the state’s long-term demographic shift[23] means more Georgians will vote Democratic.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter[24].]

As large groups of people move into the state from elsewhere, many of them are far more liberal than the current Georgia population[25]. And just like in other states, younger people in Georgia tend to be more liberal and prone to vote Democratic[26] than their parents’ and grandparents’ generation[27].

Gerrymandering districts may slow the electoral effects of these demographic changes. But creating long lines and increasing voter identification requirements will not reduce voting by enough to make a real difference. If anything, the new, restrictive laws appear to be more about rallying the Republican base[28] than changing electoral outcomes.

That said, it would be unwise to ignore even these low levels of voter suppression. If people are comfortable with these rules, that could pave the way for higher levels of suppression, which could have larger effects, up to and including unassailable single-party political control that serves to undermine U.S. democracy.

References

- ^ outrage (www.voanews.com)

- ^ criticism (time.com)

- ^ voting laws in Georgia (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ similar efforts in other states (fivethirtyeight.com)

- ^ voting more difficult (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ My research (scholar.google.com)

- ^ partisan gerrymandering efforts actually work against voter suppression measures (medium.com)

- ^ African Americans from voting (ballotpedia.org)

- ^ undermined public support for those laws (www.civilrightsteaching.org)

- ^ protect voting integrity (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ save taxpayer money (www.governing.com)

- ^ make voting more difficult for poorer populations (www.ajc.com)

- ^ don’t meaningfully affect voter turnout (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ does not give either party an electoral advantage (siepr.stanford.edu)

- ^ AP Photo/Ben Gray (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ one out of 56 state Senate races and seven out of 180 state House races (results.enr.clarityelections.com)

- ^ opposing impacts of gerrymandering and voter suppression (medium.com)

- ^ impacted by gerrymandering (www.gpb.org)

- ^ almost certainly be equally or more gerrymandered (theconversation.com)

- ^ 2018 gubernatorial election (results.enr.clarityelections.com)

- ^ 2021 U.S. Senate runoffs (results.enr.clarityelections.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Alex Brandon (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ long-term demographic shift (www.cnn.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ more liberal than the current Georgia population (theconversation.com)

- ^ prone to vote Democratic (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ parents’ and grandparents’ generation (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ rallying the Republican base (www.newsweek.com)

Authors: Bernard Tamas, Associate Professor of Political Science, Valdosta State University