US postpones Afghanistan troop withdrawal in hopes of sustaining peace process: 5 essential reads

- Written by Catesby Holmes, International Editor | Politics Editor, The Conversation US

The United States will bring home its over 3,000 remaining soldiers in Afghanistan by Sept. 11, 2021[1], delaying its planned withdrawal for five months in an effort to bolster faltering peace talks between the Afghan government and Taliban insurgent group.

The new troop withdrawal date is symbolic, marking the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 terror attacks that within weeks led to the U.S. invasion of Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. But it fails to meet former President Donald Trump administration’s planned May 1 troop withdrawal, which was negotiated with the Taliban as part of a 2020 U.S. peace accord with the group.

U.S. intelligence agencies[2] and many security analysts worried that a U.S. exit from Afghanistan on the earlier date would undermine peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government and potentially lead the Taliban to regain control of the country.

The war in Afghanistan has been long, complicated and deadly, and the road to peace fraught. Here are five stories explaining the history of the Afghan conflict and the faltering peace process.

1. Negotiations to end a ‘forever war’

First, some history on how the U.S. ended up at war with the Taliban.

“It was on Afghan soil that Osama bin Laden hatched the plot to attack the U.S.,” wrote Abdulkader Sinno, an Afghanistan expert at Indiana University, in a 2019 article about the possibility of the U.S. ending its war there[3]. “The Taliban, the de facto rulers of much of Afghanistan in the wake of a bloody civil war, had given bin Laden and his supporters shelter.”

Former U.S. President Donald Trump long signaled his intention to end America’s “forever wars” like the conflict in Afghanistan. In 2018, his secretary of defense – then James Mattis – agreed to negotiate a U.S. withdrawal directly with the Taliban, rather than in three-way talks that included the Afghan government.

The move acknowledged there was “little hope for an outright U.S. victory over the Taliban at this point,” wrote Sinno.

And for the Taliban, that was a win. They had fought “the world’s strongest military power to a stalemate,” Sinno wrote.

A market in the Old City of Kabul, Afghanistan, Sept. 8, 2019.

AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi[4]

A market in the Old City of Kabul, Afghanistan, Sept. 8, 2019.

AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi[4]

2. Troop withdrawal

On Nov. 17, 2019, Trump announced the U.S. would withdraw about half of its 4,500 troops from Afghanistan as part of a cease-fire agreement with the Taliban – a prelude to U.S. peace talks with the Taliban.

The large troop reduction was a blow to Afghanistan’s U.S.-trained national army[5], which had seen 45,000 troops killed from 2015 to 2019 in the conflict with the Taliban, according to scholar Brian Glyn Williams, who worked on the U.S. Army’s Information Operations team in eastern Afghanistan during the war.

The Afghanistan National Army relies on American troops for “essential training, equipment and other support,” wrote Williams.

Williams said Trump’s withdrawal schedule may also signal U.S. weakness to the ethnic Pashtun tribes of southeast Afghanistan.

“These 60 tribes, or clans, have for centuries maintained – and shifted – the country’s balance of military and political power. They are always calculating which of the rival factions or warring parties is in the strongest position and seeking to join that side,” wrote Williams.

3. Peace deal is signed

The U.S. in February 2020 signed its peace deal with the Taliban, following a weeklong truce and 18 months of stop-and-go negotiations.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other U.S. officials meet with senior Taliban leaders in Doha, Qatar, in November 2020.

Patrick Semansky/Pool/AFP via Getty Images[6]

Former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other U.S. officials meet with senior Taliban leaders in Doha, Qatar, in November 2020.

Patrick Semansky/Pool/AFP via Getty Images[6]

The four-part agreement committed the U.S. to withdrawing the rest of its soldiers from Afghanistan by May 1, 2021 – the date that Biden just pushed back.

In exchange, the Taliban agreed to enter talks with the Afghan government, and to bar extremist groups like al-Qaida from using Afghanistan as a base to attack the U.S. and its allies.

“But peace in Afghanistan will take more than an accord,” wrote Elizabeth B. Hessami, a scholar of peace-building at Johns Hopkins University. In an article published shortly after the accord was signed[7], Hessami wrote, “History shows that economic growth and better job opportunities are necessary to rebuild stability after war.”

Hessami noted that insurgent groups typically recruit people who “desperately need an income.”

Wired magazine reported back in 2007 that the Taliban paid its soldiers far better than the Afghan government paid its military.

“Creating well-paid alternatives to extremist groups, then, is a critical piece in solving Afghanistan’s national security puzzle,” wrote Hessami.

4. Can the Taliban be trusted?

In September 2020, six months after the U.S.-Taliban accord, the Taliban entered into talks with the Afghan government in Doha, Qatar. The two sides are supposed to establish a comprehensive cease-fire and negotiate a potential power-sharing agreement.

But Sher Jan Ahmadzai, director of the Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska Omaha, questions whether the Taliban are negotiating in good faith[8]. In the months after the U.S.-Taliban accord, violence levels in Afghanistan actually increased.

“Some Taliban fighters have insisted they will continue their jihad ‘until an Islamic system is established,’” he wrote, “leading to concerns that the organization is not actually committed to peace.”

“Many question whether the Taliban can be held accountable for what they’ve promised,” wrote Ahmadzai.

For example, international and domestic observers of the Afghan peace process have also been unable to confirm that the Taliban have actually severed their relationship with al-Qaida.

Afghans also “fear losing the meaningful achievements that came out of international engagement in Afghanistan, such as women’s empowerment, increased freedom of speech and a more vibrant press,” according to Ahmadzai.

5. What’s at stake

Biden delayed troop withdrawal in an attempt to secure a deal between the Taliban and the Afghan government that protects such rights. If peace talks collapse, Afghan women may have the most to lose.

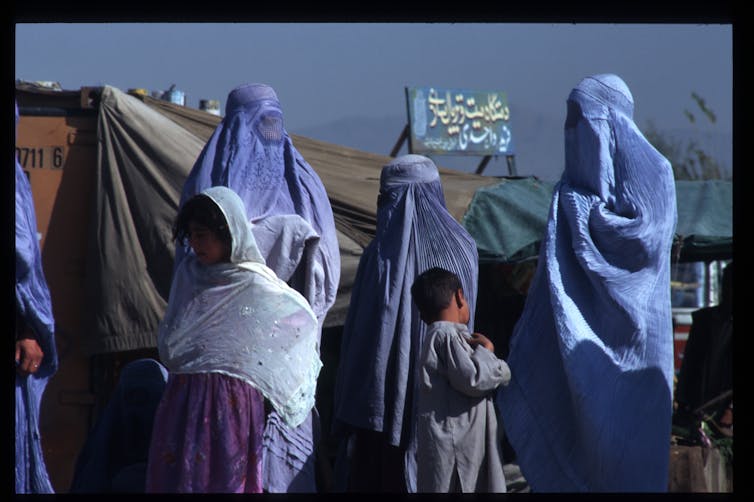

Women were required to be fully veiled in public when the Taliban ruled Afghanistan. Kabul, 1996.

Roger Lemoyne/Liaison[9]

Women were required to be fully veiled in public when the Taliban ruled Afghanistan. Kabul, 1996.

Roger Lemoyne/Liaison[9]

“The Taliban’s rule of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 was the darkest time for Afghan women,” wrote the women’s rights scholars Mona Tajali and Homa Hoodfar in a March 5, 2021, article[10].

“Assuming an austere interpretation of Islamic Sharia and Pashtun tribal practices, the group limited women’s access to education, employment and health services. Women were required to be fully veiled and have male escorts.”

Women have been largely excluded from the Doha negotiations. One of just four female negotiators on the Afghan government’s 21-member team, Fawzia Koofi, survived an assassination attempt, apparently by the Taliban.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today[11].]

References

- ^ bring home its over 3,000 remaining soldiers in Afghanistan by Sept. 11, 2021 (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ U.S. intelligence agencies (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ in a 2019 article about the possibility of the U.S. ending its war there (theconversation.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi (www.apimages.com)

- ^ blow to Afghanistan’s U.S.-trained national army (theconversation.com)

- ^ Patrick Semansky/Pool/AFP via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ article published shortly after the accord was signed (theconversation.com)

- ^ questions whether the Taliban are negotiating in good faith (theconversation.com)

- ^ Roger Lemoyne/Liaison (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ March 5, 2021, article (theconversation.com)

- ^ Sign up today (theconversation.com)

Authors: Catesby Holmes, International Editor | Politics Editor, The Conversation US