Jewish Americans changed their names, but not at Ellis Island

- Written by Kirsten Fermaglich, Associate Professor, Michigan State University

A well-worn joke in American Jewish culture[1] goes like this. A Jewish immigrant landed at Ellis Island in New York. The procedures were confusing, and he was overwhelmed by the commotion. When one of the officials asked him “What is your name?” he replied, “Shayn fergessen,” which in Yiddish means “I’ve already forgotten.” The official then recorded his name as Sean Ferguson.

Today, members of many white ethnic groups – including Jews, Italians and Poles – believe[2] that insensitive or ignorant Ellis Island officials changed their families’ names when they arrived in the U.S. to make them sound more American.

But there is actually much more evidence demonstrating that Jews and members of other white ethnic groups changed names on their own. In the research for my forthcoming book[3], I looked at legal name change petitions in New York City throughout the 20th century showing that thousands of Jewish immigrants and their children indeed changed their own names.

As American Jews celebrate Jewish American Heritage Month[4] this May, it is worth revisiting where and why the portrait of coercive Ellis Island name changing emerged.

No evidence in popular literature

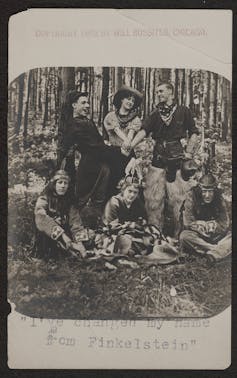

Yonkle the Cowboy Jew.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.[5]

Yonkle the Cowboy Jew.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.[5]

Historians Marian Smith[6] and Vincent Cannato[7] argue convincingly that insensitive Ellis Island officials did not forcibly change immigrants’ names[8]. In fact, immigration procedures did not[9] typically include the question “What is your name?” Bureaucrats simply checked immigrants’ names to make sure they matched the names already listed on ships’ passenger lists.

Evidence from popular literature further supports their argument. Between 1892 and 1920, when thousands of immigrants passed through the immigration station on Ellis Island each day, there were no descriptions of Ellis Island name changing in popular magazines or books. And even after immigration slowed significantly in the 1920s, popular books and magazines for the next four decades did not typically describe Ellis Island officials changing immigrant names.

During this period, popular literature explored a variety of relevant topics such as the origins and usage of names[10], the social psychology of name changing[11], Jewish humor[12] and Jewish immigration[13], but none addressed name changing at Ellis Island.

Indeed, one 1969 Jewish humor book[14] even told a joke with the Sean Ferguson punchline. But the joke was about a Yiddish actor who went to California to become a movie star. All through the train ride, he worked on memorizing a stage name, only to forget it when he came face to face with an imposing Hollywood producer.

Cultural changes of the 60s and 70s

It was not until the 1970s that the image of Ellis Island name changing took hold of the American imagination. One popular 1979 book[15] about Ellis Island and the immigrant experience, for example, described officials who were “casual and uncaring on the matter of names.”

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 film “The Godfather, Part II” featured an insensitive immigration officer giving young Vito Corleone his name.

What I’d like to argue is that the culture of the late 1960s and 1970s shaped these portraits of Ellis Island name changing. After the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act[16] eliminated the discriminatory immigration quotas that had restricted immigration from southern and eastern Europe, American popular culture began to tell new stories that valorized the success of immigrants[17] from those very regions.

Ellis Island itself – where Lyndon Johnson signed the 1965 act – transformed in the public mind from a set of abandoned buildings to a prominent symbol[18] of European immigrants’ struggles and triumphs.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act at Ellis Island.

LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto[19]

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act at Ellis Island.

LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto[19]

The late 1960s and 1970s also witnessed significant challenges to the authority of the United States government: The Pentagon Papers[20] showed that the government had misled the American people, as the U.S. committed more and more troops to Vietnam. Persistent racial inequality exploded in riots[21] in cities throughout the country. And the Watergate scandal exposed criminality and obstruction of justice[22] at the highest levels of government.

Portraits of involuntary name changing at Ellis Island fit both with the island’s new prominence as a symbol of immigration, and with growing distrust of government authority.

Name changing a betrayal of family values?

Ellis Island name changing also fit another emerging theme in American culture in the 1970s: a quest for authenticity. Historian Matthew Frye Jacobson[23] has documented the quest of many white ethnic groups during this era, including Jews, to seek “authentic” culture to bolster their ethnic identities.

With films like “The Godfather” and “Hester Street,”[24] which portrayed the challenges immigration posed for one young Jewish family in New York, American culture turned to the Old World – the European countries from which white immigrants had immigrated – as a source for family values and communal integrity. And within this context, changing names seemed like a betrayal of family, community and identity.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, novels, films and plays that portrayed Jewish life, such as Wendy Wasserstein’s[25] play “Isn’t It Romantic?”[26] and Barry Levinson’s[27] movie, “Avalon,” represented name changers as phonies or sellouts.

Although Jews were not the only ones to experience this longing for authenticity, my research[28] suggests they changed their names in disproportionate numbers compared with other groups in response to American anti-Semitism.

In a culture that had begun to embrace the Old World as a source of authentic values, the fact that their parents and grandparents voluntarily changed their own names from their original Jewish ones may have been painful for many American Jews to accept. Blaming insensitive government officials at Ellis Island for erasing Jewish names was a much easier task.

But this emphasis upon Ellis Island only obscured the complicated reasons why Jews actually changed their own names.

The Sean Ferguson joke is thus more than a simple joke. It illustrates the ways that Jewish people have struggled, and continue to struggle, with their identity in America. It shows how hard it is to grapple with the past, but also how important that grappling is.

References

- ^ well-worn joke in American Jewish culture (books.google.com)

- ^ believe (forward.com)

- ^ research for my forthcoming book (nyupress.org)

- ^ Jewish American Heritage Month (www.jewishheritagemonth.gov)

- ^ Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. (www.loc.gov)

- ^ Marian Smith (www.iajgs.org)

- ^ Vincent Cannato (www.umb.edu)

- ^ did not forcibly change immigrants’ names (www.harpercollins.com)

- ^ did not (www.ilw.com)

- ^ origins and usage of names (books.google.com)

- ^ social psychology of name changing (books.google.com)

- ^ Jewish humor (books.google.com)

- ^ Jewish immigration (books.google.com)

- ^ one 1969 Jewish humor book (books.google.com)

- ^ popular 1979 book (books.google.com)

- ^ 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act (www.history.com)

- ^ valorized the success of immigrants (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ prominent symbol (www.harpercollins.com)

- ^ LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto (www.lbjlibrary.org)

- ^ Pentagon Papers (www.archives.gov)

- ^ riots (news.google.com)

- ^ exposed criminality and obstruction of justice (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Matthew Frye Jacobson (afamstudies.yale.edu)

- ^ “Hester Street,” (variety.com)

- ^ Wendy Wasserstein’s (www.biography.com)

- ^ “Isn’t It Romantic?” (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Barry Levinson’s (www.imdb.com)

- ^ my research (www.jstor.org)

Authors: Kirsten Fermaglich, Associate Professor, Michigan State University

Read more http://theconversation.com/jewish-americans-changed-their-names-but-not-at-ellis-island-96152