Far-right groups move to messaging apps as tech companies crack down on extremist social media

- Written by Kevin Grisham, Professor of Global Studies, California State University San Bernardino

Right-wing extremists called for open revolt against the U.S. government for months on social media[1] following the election in November. Behind the scenes on private messaging services, many of them recruited new followers, organized and planned actions, including the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

Encrypted messaging platforms like Telegram, which was launched in 2013, have become places for violent extremists to meet up and organize. Telegram serves a dual purpose. It created a space where conversations can occur openly in the service’s public channels. Those who wanted more privacy can message one another through private chats.

In these private chats, violent extremists can share tactics, organize themselves and radicalize, something I’ve observed in my research of hate and extremism[2]. New Telegram users are exposed to violent extremist beliefs on the public side of Telegram and then group members carry out the logistics of recruiting and organizing in the private chats.

Online extremism’s long history

Violent extremists’ use of the internet is not new. In the 1990s, electronic bulletin boards and simple websites allowed white supremacists, neo-Nazis, anti-government groups and a variety of other violent extremists to sell their ideologies and recruit[3].

In the 2000s, mainstream social media platforms like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter became the new way for extremists to recruit and spread their beliefs. For many years, these groups cultivated their online presences and gained followers on these mainstream platforms.

Alternative social media outlets, including Gab, 4chan and 8kun (formerly 8chan), developed shortly thereafter. These provided forums where violent extremists could post hate speech and calls for violence without fear of being blocked.

Studies have shown that after 2010 social media generally contributed to an increase in radicalization[4] of individuals by violent extremist movements in the U.S.

During this time, extremist groups have shifted their organizing to messaging platforms, particularly Telegram[5]. In the case of far-right violent extremists, Telegram served as a major meeting spot and venue for coordinating their efforts. For example, users were able to share links in the private chats[6] where individuals could buy guns and other weapons.

Unintended consequences

As these extremist movements proliferated online, some social media outlets attempted to stop it. Facebook, YouTube and Twitter began to block these types of users in recent years in an arguably limited manner[7]. Mainstream conservative audiences on Facebook and Twitter left for new platforms like Parler that were seen as more friendly to conservative views.

Conservative political leaders and pundits like U.S. Rep. Devin Nunes and Fox News talk show host Sean Hannity helped this migration by promoting the new conservative platforms. This created a bridge[8] between those coming from the nonviolent side of the far right and far-right violent extremists, which in turn created an environment that set the stage for the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The migration to private channels on messaging platforms also made it more difficult for law enforcement agencies[9] to track far-right groups’ activities.

The attack on the Capitol

Throughout the early spring and summer of 2020, disinformation about the upcoming U.S. elections[10] was plentiful. As Twitter, Facebook and YouTube placed greater restrictions on user content, far-right violent extremist and conspiracy movements, in particular the QAnon movement, began to migrate to Parler, Gab and increasingly to Telegram.

In the aftermath of the 2020 U.S. elections and the defeat of Donald Trump, these spaces gained greater importance as places for radicalization. People who have never seen content by the Proud Boys, QAnon, militias and anti-government groups were exposed to it in the public channels of Telegram. People with conservative or pro-Trump views embraced some of this new content[11] because it offered an alternative reality they preferred.

Calls for protests and violent opposition[12] against the counting of the Electoral College votes by the U.S. Congress on Jan. 6 could be found throughout the platforms, particularly on Telegram. In my tracking of content on Telegram, MeWe and other encrypted platforms on Jan. 5 and the day of the attack, I saw calls for violent opposition and civil war. Some Republicans became targets of ridicule and claims they were traitors as they called for the counting to proceed unhindered. Vice President Mike Pence was labeled a traitor, and calls for his arrest and execution could be seen on Twitter accounts and throughout Telegram.

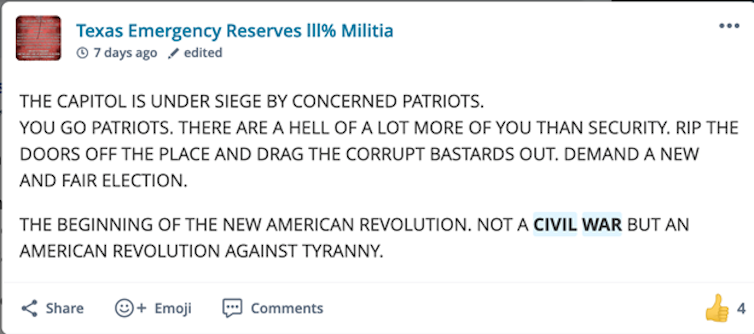

For months, Telegram private chats allowed people to organize and coordinate their actions in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6[13]. As the violence unfolded at the U.S. Capitol and rioters got into offices and various rooms in the building, participants used a wide range of social media platforms in the far-right online ecosystem to both report the events and to call more people to arms.

A post about the attack on the U.S. Capitol on the alternative social media platform MeWe, posted Jan. 6, 2021.

Screen capture by Kevin Grisham, CC BY-NC-ND[14]

A post about the attack on the U.S. Capitol on the alternative social media platform MeWe, posted Jan. 6, 2021.

Screen capture by Kevin Grisham, CC BY-NC-ND[14]

The aftermath of Jan. 6

In the aftermath of the attack on the Capitol, Facebook began barring individuals – including Trump – from their platforms. In the case of Parler, Amazon canceled the hosting services[15] for its site, and it went dark. As a result, a significant number of Parler users migrated to Telegram. Parler is attempting to return to service[16] with help from a Russian internet company.

As announcements went out that Parler was going dark, various individuals and groups on Telegram created parallel channels on Telegram. It became a lifeboat[17] for those users who needed a new home. Megan Squire, a professor of computer science at Elon University, estimated one channel associated with the Proud Boys grew 54% from Jan. 6 to Jan. 12[18].

As the migration continues[19], I’ve observed a nexus between members of the MAGA movement and violent far-right extremists is growing. This led to more calls for violence and protests[20] at state capitols and at the Inauguration Day activities in Washington, D.C., though no violence occurred. People who expressed a willingness to perform these actions found support in this rapidly transforming far-right ecosystem that has Telegram at its center.

For years, social media allowed far-right violent extremists to recruit and organize on a multitude of platforms. This online bridge between violent and nonviolent individuals helped lay the groundwork for the events Jan. 6.

Now, with scores of arrests for the Capitol attack, Trump out of power and Joe Biden in office, far-right groups are using platforms like Telegram and Gab to take stock[21] of their setbacks. If they do regroup and plan further violent actions, they are likely to do so on the same platforms.

References

- ^ for months on social media (theconversation.com)

- ^ research of hate and extremism (www.csusb.edu)

- ^ sell their ideologies and recruit (doi.org)

- ^ contributed to an increase in radicalization (www.start.umd.edu)

- ^ particularly Telegram (www.counterextremism.com)

- ^ share links in the private chats (icct.nl)

- ^ arguably limited manner (www.brookings.edu)

- ^ created a bridge (theconversation.com)

- ^ more difficult for law enforcement agencies (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ disinformation about the upcoming U.S. elections (www.politico.com)

- ^ embraced some of this new content (www.pbs.org)

- ^ Calls for protests and violent opposition (www.vox.com)

- ^ organize and coordinate their actions in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6 (www.vox.com)

- ^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Amazon canceled the hosting services (theconversation.com)

- ^ attempting to return to service (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ became a lifeboat (www.motherjones.com)

- ^ estimated one channel associated with the Proud Boys grew 54% from Jan. 6 to Jan. 12 (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ the migration continues (www.axios.com)

- ^ more calls for violence and protests (theintercept.com)

- ^ take stock (www.nytimes.com)

Authors: Kevin Grisham, Professor of Global Studies, California State University San Bernardino