How engineering can contribute to a reimagining of the US public health system

- Written by Woodrow W. Winchester III, Graduate Program Director, Professional Engineering Programs, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Of the many things that COVID-19 has made abundantly clear to us, surely one of them is a newfound realization that public health has become increasingly complex. Understanding the challenges to public health – that is, the task of guarding the well-being of the U.S. population – is essential now more than ever.

As an engineer, design futurist[1] and graduate program director[2], I have seen how COVID-19 has transformed how public health preparedness is viewed and understood. Some say the pandemic has delivered an urgency for a reimagining of public health[3].

From problems in producing PPE that demonstrate the vulnerabilities in critical supply chains[4] to solutions in vaccine distribution challenges that leverage innovative public-private partnerships[5], new perspectives[6] and approaches[7] to public health are necessary.

A way to accomplish this: using health care engineering[8], or more specifically, the application of systems engineering in health care. Systems engineering[9] is defined as an interdisciplinary approach and means to enable the realization of successful systems. These could include such complex systems as aircraft and spacecraft systems. Already, this concept is flourishing[10]. Research centers throughout the U.S., including those at the Mayo Clinic[11] and Northeastern University’s Healthcare Systems Engineering[12], suggest challenges such as patient safety[13] could be made better by applying systems engineering principles and techniques through more holistic and human-centered approaches to systems design.

These efforts have proven helpful to health care delivery in response to COVID-19[14]. But more is required, particularly in the use of systems engineering in informing public health responses and interventions[15]. A field of public health systems engineering is needed.

Its intent: to develop and apply systemic and integrated approaches to understanding and solving public health problems. Formalizing a field of public health systems engineering – focused on health care at the population level – offers the needed research and educational pathways to advance this work.

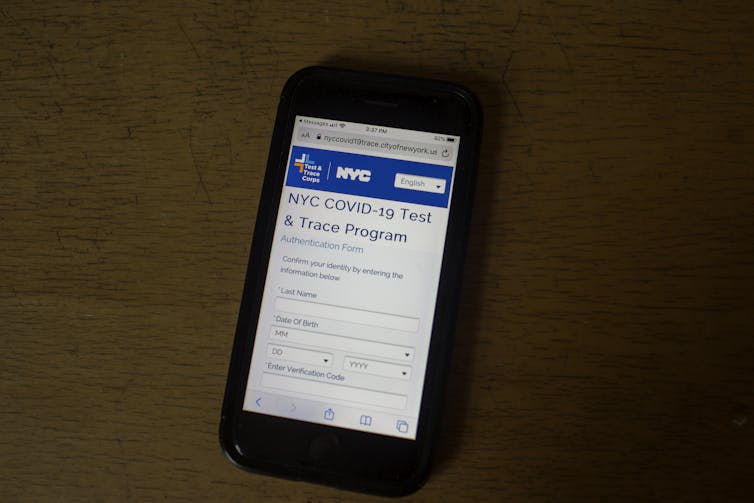

Effective contact tracing is critical to reducing the impact of the pandemic.

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images[16]

Effective contact tracing is critical to reducing the impact of the pandemic.

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images[16]

The systems engineering imperative

Examples of this include designing and developing[17] personal protective equipment, repairing the vulnerabilities in the food supply chain[18], and grappling with vaccine logistics[19]. COVID-19 has made clear the growing interconnected, interdisciplinary and multifaceted nature of public health’s future. In partnering with public health, systems engineering can mature mindsets (systems thinking[20]) and practices that can aid in meeting this future.

Illustrating this notion are efforts by Pinar Keskinocak[21], the co-founder and director of the Center for Health and Humanitarian Systems[22] at Georgia Institute of Technology, and her colleagues. In a recent interview[23], Keskinocak said: “Whenever there is a complex problem, it needs serious analysis or technology and that’s where an engineer comes in. This is exactly the situation now, very complex, dynamic and uncertain. It’s difficult to understand what’s going on or make decisions just by sitting around a table and discussing. We need expertise in engineering.”

And it’s not just technical or technological concerns. Human systems integration[24] or human factors considerations are equally central in systems engineering approaches. For example, building trust[25] with Black Americans is vital to the success of contact tracing. Public health systems engineering could advance efforts[26] to develop more equitable practices[27] that could improve Black participation. An example is works that further the development of requirements elicitation techniques such as storytelling[28] that provide a more comprehensive understanding of users and their context of use. These more inclusive practices would consider historical context[29] and support more community-led public health design engagements[30].

COVID-19 has demonstrated the difficulties in the mass production and distribution of a vaccine.

Paul Hennessy/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images[31]

COVID-19 has demonstrated the difficulties in the mass production and distribution of a vaccine.

Paul Hennessy/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images[31]

A ‘test we cannot fail’

COVID-19 has often been called a stress test for public health. COVID-19 will not be our last or worst pandemic; our emerging understanding of the public health implications of climate change[32] further spotlights this growing need. “What is true for COVID is true for climate change,” says a recent Scientific American opinion piece[33]. “We’re not prepared. Part of the gap is a knowledge gap: We haven’t done the needed research, and we lack critical information.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[34].]

As the future of public health[35] is likely to become increasingly digital, the technical understanding[36] and holistic approach offered by systems engineering will begin to fill this critical public health knowledge gap. Fortunately, efforts[37] are emerging in meeting these needs. Emory University’s Health DesignED[38], the Design Institute for Health[39] at the Dell Medical School, Vanderbilt’s Medical Innovators Development Program[40] and recent initiatives such as those at Johns Hopkins[41] are examples. The time is ripe for evolving the field of public health systems engineering. It is something the U.S. public health system desperately needs.

References

- ^ design futurist (jfsdigital.org)

- ^ graduate program director (professionalprograms.umbc.edu)

- ^ a reimagining of public health (ajph.aphapublications.org)

- ^ vulnerabilities in critical supply chains (fortune.com)

- ^ innovative public-private partnerships (www.floridadisaster.org)

- ^ perspectives (www.fastcompany.com)

- ^ approaches (phillyfightingcovid.com)

- ^ health care engineering (hbr.org)

- ^ Systems engineering (sebokwiki.org)

- ^ is flourishing (www.hindawi.com)

- ^ Mayo Clinic (www.mayo.edu)

- ^ Northeastern University’s Healthcare Systems Engineering (www.hsye.org)

- ^ patient safety (www.healthaffairs.org)

- ^ COVID-19 (doi.org)

- ^ public health responses and interventions (www.sebokwiki.org)

- ^ Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ designing and developing (www.fastcompany.com)

- ^ food supply chain (www.wbur.org)

- ^ vaccine logistics (thehill.com)

- ^ systems thinking (www.thinknpc.org)

- ^ Pinar Keskinocak (www2.isye.gatech.edu)

- ^ Center for Health and Humanitarian Systems (chhs.gatech.edu)

- ^ interview (www.asme.org)

- ^ Human systems integration (www.sebokwiki.org)

- ^ building trust (www.apa.org)

- ^ efforts (www.newswise.com)

- ^ equitable practices (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ storytelling (ekaprdweb01.eurekalert.org)

- ^ consider historical context (medium.com)

- ^ community-led public health design engagements (dl.acm.org)

- ^ Paul Hennessy/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ public health implications of climate change (climate.org)

- ^ Scientific American opinion piece (www.scientificamerican.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ future of public health (www.nature.com)

- ^ the technical understanding (www.vice.com)

- ^ efforts (www.sebokwiki.org)

- ^ Health DesignED (www.emoryhealthdesigned.com)

- ^ Design Institute for Health (dellmed.utexas.edu)

- ^ Medical Innovators Development Program (medschool.vanderbilt.edu)

- ^ Johns Hopkins (engineering.jhu.edu)

Authors: Woodrow W. Winchester III, Graduate Program Director, Professional Engineering Programs, University of Maryland, Baltimore County