Rooting out racism in children's books

- Written by Lindsay Pérez Huber, Associate Professor, College of Education , California State University, Long Beach

Ten years ago, I sat down with my then 8-year-old daughter to read a book before bedtime. The book was sort of a modern-day “boy who cried wolf” story, only it was about a little girl named Lucy who had a bad habit of telling lies.

In the story, Lucy borrowed her friend Paul’s bike and crashed it. Lucy lied to Paul, telling him “a bandit” jumped in her path and caused the crash. I saw the image and stopped reading. I was stunned. The image on the page was the racist stereotype[1] of the “Mexican bandit” wearing a serape, sombrero and sandals.

By training, I am a critical race theorist in education[2] who understands that racism is ingrained into the fabric of our society in general, and in educational institutions in particular. One area of my research[3] is about how people of color experience racial microaggressions[4], which are often subtle but significant attacks – verbal or nonverbal. They can take on many forms, such as remarks about one’s identity, and occur because of institutionalized racism[5].

Although I am an academic who studies racism, in that moment, as a parent, I felt unsure about how to help my daughter understand what we were seeing in that book. Around the same time, I read an opinion piece by children’s book author Christopher Meyers in The New York Times titled “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature[6].” It outlined the problem of racial representation in children’s literature.

The problem of scarcity

These personal encounters prompted me to investigate the portrayals of people of color in children’s books. I learned that the Cooperative Children’s Book Center[7] (CCBC), a research library based at the University of Wisconsin, has been collecting data on the number of children’s books published in the U.S. authored by and about people of color.

The data is disturbing.

In 2015 – when I began this research – there were 85 books published in the U.S. that included Latinx characters from the 3,200 children’s books the center received that year. That’s about 2.5% of the total, whereas Latinx kids represent about 1 in 4 school children[8] in the U.S.

Since then, there has been an upward trend for all ethnic or racial groups. However, books written by and about people of color remain a very small proportion of books published each year. The most recent CCBC data reports books with Latinx characters were about 6%[9] of the more than 4,000 children’s books the center received in 2019.

The lack of representation of communities of color in children’s books is another longstanding problem – one that has persisted since at least the 1920s when renowned sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois first expressed his concerns about anti-Black racism in children’s books[10]. Books can serve as important tools for children to develop their own sense of self and identity. When children of color do not see themselves in the books they read, this sends the message that they and their communities are not important.

In a study published in 2020, my colleagues and I used critical race theory to develop a rubric[11] to critically analyze racial representations in children’s books. Drawing from this research, here are five questions to consider when choosing books about people of color:

Children’s books on display during a Black Lives Matter protest.

Cole Burston/Toronto Star via Getty Images[12]

Children’s books on display during a Black Lives Matter protest.

Cole Burston/Toronto Star via Getty Images[12]

1. What roles do the characters of color play?

It is important to see people of color represented in a wide array of characters to avoid falling into racist tropes and stereotypes. When characters of color are present, it is important to recognize the position they play in the story line. Children should have the opportunity to see characters of color as main characters, central to the stories they read.

For example, in Pam Muñoz Ryan’s “Esperanza Rising[13],” the story follows Esperanza, a young Latina girl whose affluent Mexican family loses everything in a series of tragic events that force her and her mother to migrate North to California, where they become farmworkers.

For younger readers, Matthew A. Cherry’s “Hair Love”[14] tells the story of a young African American girl named Zuri, who wants to celebrate a special day with a special hairstyle, which she gets with the help of her father.

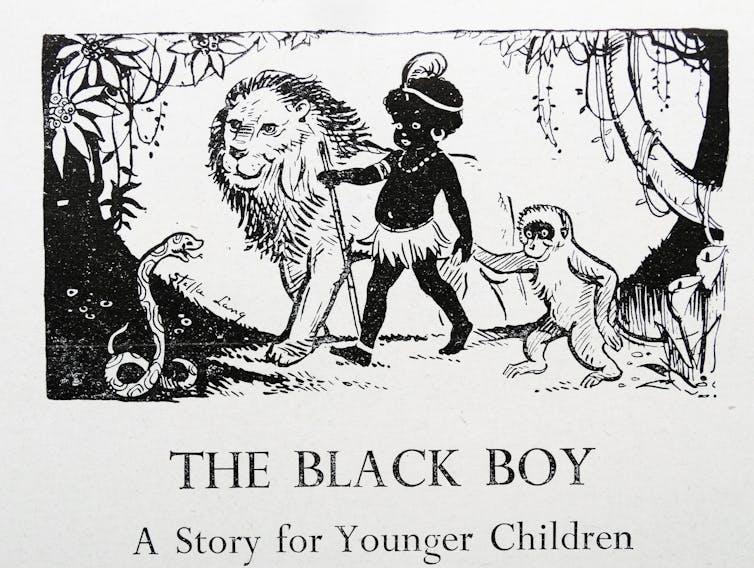

‘The Story of Little Black Sambo,’ a chidren’s book published in 1899, featured racial stereotypes of Black children.

Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images[15]

‘The Story of Little Black Sambo,’ a chidren’s book published in 1899, featured racial stereotypes of Black children.

Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images[15]

2. Does the book contain racial stereotypes?

Research has found that dominant perspectives of communities of color[16] are often guided by views that they are culturally deficient. These deficit views often blame people of color for the social inequities they face, such as low educational attainment or poverty.

In my view, it is important to identify whether stories about people of color perpetuate or challenge these views.

One example of deficit views would be the book with a character that perpetuates the racist stereotype of the Mexican bandit, which I mentioned earlier. Images like those have historically targeted[17] Latinas and Latinos in the U.S.

3. Are characters represented in culturally authentic ways?

Culturally authentic stories are accurate portrayals of a particular culture. For example, the book “I’m New Here[18]” by Anne Sibley O'Brien is a story about three young students from Somalia, Guatemala and Korea who immigrate to the U.S. and come to school for the first time, but does not recognize how these students can have different immigration experiences from one another.

Language used by and between characters is an important signal for cultural authenticity. Education scholar Carmen Martínez Roldán has found that mock Spanish[19] is used frequently in the best-selling children’s book series “Skippyjon Jones” by Judy Schachner. Mock Spanish, according to Roldán, is the borrowing of selective aspects of Spanish that serve to mock those who speak it, such as phrases like “no problem-o” and “no way Jose.”

4. Do the books include the bigger picture?

Effective storytelling about people of color should provide a broader historical, social, political and other context. This gives children the ability to understand how everyday experiences exist within the larger society.

For early readers, these contexts are usually subtle clues that can help children better understand a broader issue. For example, in “We Are Water Protectors,[20]” author Carole Lindstrom warns of the effects of environmental pollution through Indigenous perspectives of water as a precious resource to be protected.

Context becomes more explicit for older readers in chapter books and books aimed at middle or high school students, like George Takei’s graphic novel “They Called Us Enemy[21],” which is about his personal experience growing up in a Japanese internment camp[22] during World War II.

5. Who has power and agency in the story?

There are many vantage points from which a story can be told. When a book tells a story through the eyes of a character of color, there is a power assigned to the character in the telling of their own story. This strategy gives the character agency to construct the narrative, and to resolve the ending. Juana Martinez-Neal’s “Alma and How She Got Her Name[23]” is a moving story of a little girl who learns the power of her name is connected to the history of her family.

One problematic strategy I have seen in books with characters of color is the use of nameless characters. Using general references like “the girl” or “the boy” shifts power and agency away from the character and creates a social distance[24] between the story and the reader, rather than make a humanistic connection.

For example, Jairo Buitrago’s[25] “Two White Rabbits[26]” tells an important story of a young girl’s migration north from Mexico with her father. However, there is a missed opportunity for readers to connect with the main character, who is not given a name, and thus to her migration story.

One of the most important things parents can do is to engage with their child readers about what they are reading and seeing in books. Helping children to make sense of what they see, challenge ideas and recognize problematic storytelling are critical tools they can use to read the world around them.

References

- ^ racist stereotype (doi.org)

- ^ critical race theorist in education (doi.org)

- ^ my research (scholar.google.com)

- ^ racial microaggressions (www.tcpress.com)

- ^ because of institutionalized racism (www.tcpress.com)

- ^ The Apartheid of Children’s Literature (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Cooperative Children’s Book Center (ccbc.education.wisc.edu)

- ^ Latinx kids represent about 1 in 4 school children (theconversation.com)

- ^ Latinx characters were about 6% (ccbc.education.wisc.edu)

- ^ concerns about anti-Black racism in children’s books (www.loc.gov)

- ^ develop a rubric (doi.org)

- ^ Cole Burston/Toronto Star via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Esperanza Rising (www.scholastic.com)

- ^ Hair Love” (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ dominant perspectives of communities of color (www.routledge.com)

- ^ historically targeted (utpress.utexas.edu)

- ^ I’m New Here (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ mock Spanish (search.proquest.com)

- ^ We Are Water Protectors, (us.macmillan.com)

- ^ They Called Us Enemy (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ Japanese internment camp (www.archives.gov)

- ^ Alma and How She Got Her Name (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ creates a social distance (doi.org)

- ^ Jairo Buitrago’s (groundwoodbooks.com)

- ^ Two White Rabbits (groundwoodbooks.com)

Authors: Lindsay Pérez Huber, Associate Professor, College of Education , California State University, Long Beach

Read more https://theconversation.com/rooting-out-racism-in-childrens-books-149432