Before Kamala Harris, many Black women aimed for the White House

- Written by Sharon Austin, Professor of Political Science, University of Florida

The vice president-elect of the United States is the American daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants[1].

With Joe Biden’s projected presidential win over Donald Trump[2], Sen. Kamala Harris breaks three centuries-old barriers to become the nation’s first female vice president, first Black vice president and first Black female vice president. Harris is also of Indian descent[3], making the 2020 election a meaningful first for two communities of color.

Harris wasn’t the first Black female vice presidential aspirant in American history. Charlotta Bass, an African American journalist and political activist from California, ran for vice president in 1948 with the Progressive Party[4].

Before she was Biden’s running mate, Harris was his opponent in the Democratic presidential primary. She is one of many Black American women to have aimed for the highest office in the land[5] despite great odds.

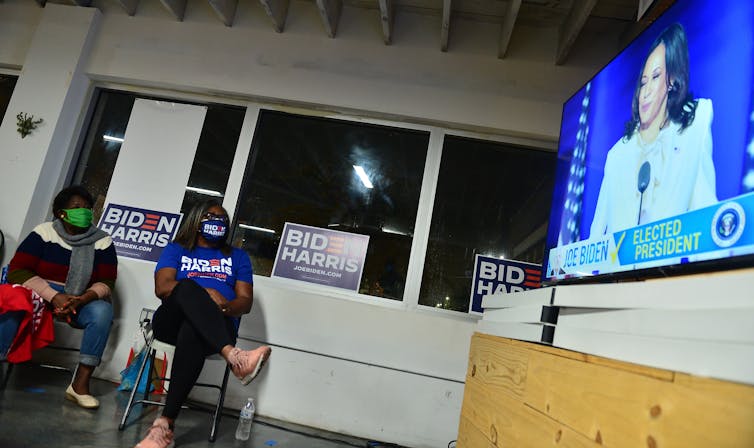

Watching Kamala Harris’s first speech as the 49th U.S Vice President-elect, Nov. 7, 2020 in Miami, Florida.

Johnny Louis/Getty Images[6]

Watching Kamala Harris’s first speech as the 49th U.S Vice President-elect, Nov. 7, 2020 in Miami, Florida.

Johnny Louis/Getty Images[6]

Hands that once picked cotton

African Americans have faced many hurdles to achieving political power in the United States, among them slavery, Jim Crow and disenfranchisement.

Black women, in particular, have hit barrier upon barrier. Women didn’t gain the right to vote in the U.S. until 1920[7], and even then Black people – women among them – still couldn’t vote in most of the South. In the 1960s, Black women helped organize the civil rights movement[8] but were kept out of leadership positions.

I address issues like these in the government and minority politics classes I teach as a political science professor[9]. But I also tell my students that Black women have a history of political ambition and achievement. As the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. said in 1984 about the progress Black voters made last century[10], “Hands that once picked cotton will now pick a president.”

Biden, himself a former vice president, understands the significance of the role.

Mark Makela/Getty Images[11]

Biden, himself a former vice president, understands the significance of the role.

Mark Makela/Getty Images[11]

Today, Black female mayors[12] lead several of the biggest U.S. cities, including Atlanta, Chicago and San Francisco. Black women are police chiefs[13], gubernatorial candidates[14], and, in growing numbers, congresswomen[15].

Now, Black women, who once had no chance of even voting for president – much less being president – see one of their own a step away from the Oval Office.

‘Unsuitable’ for the job?

Kamala Harris is a Democrat who served as California’s attorney general and later one of its senators. But, historically, most Black female presidential candidates have run as independents.

In 1968, 38-year-old Charlene Mitchell of Ohio became the first Black woman to run for president, as a communist. Like many other African Americans born in the 1930s, Mitchell joined the Communist Party because of its emphasis on racial and gender equality[16]. Black female communists fought Jim Crow, lynchings and unfair labor practices for men and women of all races[17].

Charlene Mitchell, America’s first Black female presidential candidate.

Wikimedia Commons[18]

Charlene Mitchell, America’s first Black female presidential candidate.

Wikimedia Commons[18]

Mitchell’s presidential campaign, which focused on civil rights and poverty[19], was probably doomed from the start. In 1968, many states didn’t allow communists on the ballot[20]. Media outlets from the Boston Globe to the Chicago Tribune[21] also discussed Mitchell’s “unsuitability” as a candidate because she was both Black and female[22]. Mitchell received just 1,075 votes[23].

Other independent Black female presidential candidates include community organizer Margaret Wright, who ran on the People’s Party ticket in 1976[24] and Isabell Masters, a teacher who created her own third party, called Looking Back[25] and ran in 1984, 1992 and 2004.

In 1988, psychologist Lenora Fulani became the first woman and the first African American to appear on the ballot in all 50 states. Running as an independent, she received more votes for president in a U.S. election than any other female candidate before her[26]. Teacher Monica Moorehead of the Workers World ticket[27], ran for president in 1996, 2000 and 2016.

In 2008, the year Barack Obama was elected president, Cynthia McKinney, a former U.S. representative from Georgia, was a nominee of the Green Party[28]. And in 2012, Peta Lindsay ran to unseat President Obama from the left, on the Party for Socialism and Liberation ticket[29].

Only one Black woman has ever pursued the Republican nomination: Angel Joy Charvis, a religious conservative from Florida, who wanted to use her 1999 candidacy to “to recruit a new breed of Republican[30].”

Unbought and unbossed

Those Black female presidential candidates were little known. But as the first Black female member of Congress, Shirley Chisholm had years of experience in public office and a national reputation when she became the first Black American and the first woman to seek the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972. Chisholm’s campaign slogan was “Unbought and Unbossed[31].”

Shirley Chisholm announces her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Don Hogan Charles/New York Times Co. via Getty Images[32]

Shirley Chisholm announces her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Don Hogan Charles/New York Times Co. via Getty Images[32]

Chisholm, who mostly paid for her campaign on her credit card[33], focused on civil rights and poverty[34].

She became the target of vehement sexism. One New York Times article from June 1972[35] described her appearance as, “[Not] beautiful. Her face is bony and angular, her nose wide and flat, her eyes small almost to beadiness, her neck and limbs scrawny. Her protruding teeth probably account in part for her noticeable lisp.”

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter[36].]

Chisholm received little support from either Black or female voters and won not a single primary[37].

The Black women who followed in Chisholm’s footsteps from Congress to the Democratic presidential primary, including Illinois Sen. Carol Moseley Braun[38] and Harris herself, have seen little more success. Harris was among the first 2020 Democratic primary candidates to drop out, in December 2019[39].

Challenges for Black women

Why did these candidacies and those of other Black women[40] who aimed for high office fail?

In most cases, my research finds, America’s Black female presidential candidates haven’t made the ballot. Those who did had trouble raising funds.

A mural by artist Danielle Mastrion in Shirley Chisholm State Park, which opened in 2019 in Brooklyn, New York.

Catesby Holmes, CC BY[41]

A mural by artist Danielle Mastrion in Shirley Chisholm State Park, which opened in 2019 in Brooklyn, New York.

Catesby Holmes, CC BY[41]

Because their candidacies weren’t taken seriously[42] by the media, they had trouble getting their messages heard. Historically Black female presidential candidates have received no real support from any segment of American voters[43], including African Americans and women. Generally, people – even those who might have been heartened by the idea that someone who looked like them could aspire to the White House – thought they couldn’t win[44].

As a two-term vice president who had a major role in governing under President Obama, Joe Biden knows what the office entails. In Harris, he selected a woman who not only helped him win the election but is also ready to govern.

November 2020 is a watershed year for African Americans, Asian Americans and women who’ve so long been excluded from so many aspects of politics.

This story is an updated and expanded version of an article[45] originally published on Aug. 11, 2020. A misspelling of Dr. Lenora Fulani’s name in an early tweeted version of this story has now been corrected.

References

- ^ American daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ Joe Biden’s projected presidential win over Donald Trump (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ also of Indian descent (theconversation.com)

- ^ ran for vice president in 1948 with the Progressive Party (www.aaihs.org)

- ^ aimed for the highest office in the land (www.thoughtco.com)

- ^ Johnny Louis/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Women didn’t gain the right to vote in the U.S. until 1920 (www.nps.gov)

- ^ organize the civil rights movement (theconversation.com)

- ^ political science professor (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Black voters made last century (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Mark Makela/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Black female mayors (theconversation.com)

- ^ police chiefs (www.latimes.com)

- ^ gubernatorial candidates (www.nbcwashington.com)

- ^ congresswomen (www.cawp.rutgers.edu)

- ^ its emphasis on racial and gender equality (www.thecrimson.com)

- ^ men and women of all races (www.peoplesworld.org)

- ^ Wikimedia Commons (upload.wikimedia.org)

- ^ civil rights and poverty (www.aaihs.org)

- ^ allow communists on the ballot (diva.sfsu.edu)

- ^ Boston Globe to the Chicago Tribune (www.aaihs.org)

- ^ because she was both Black and female (www.aaihs.org)

- ^ just 1,075 votes (www.jofreeman.com)

- ^ ran on the People’s Party ticket in 1976 (nursingclio.org)

- ^ called Looking Back (www.telegraph.co.uk)

- ^ more votes for president in a U.S. election than any other female candidate before her (awpc.cattcenter.iastate.edu)

- ^ Workers World ticket (www.ourcampaigns.com)

- ^ nominee of the Green Party (www.gp.org)

- ^ Party for Socialism and Liberation ticket (www.pslweb.org)

- ^ to recruit a new breed of Republican (www.orlandosentinel.com)

- ^ Unbought and Unbossed (theundefeated.com)

- ^ Don Hogan Charles/New York Times Co. via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ credit card (theundefeated.com)

- ^ civil rights and poverty (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ New York Times article from June 1972 (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Sign up for our weekly newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ not a single primary (web.archive.org)

- ^ Illinois Sen. Carol Moseley Braun (www.haverford.edu)

- ^ first 2020 Democratic primary candidates to drop out, in December 2019 (www.cnn.com)

- ^ other Black women (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ weren’t taken seriously (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ no real support from any segment of American voters (theconversation.com)

- ^ thought they couldn’t win (www.smithsonianmag.com)

- ^ article (theconversation.com)

Authors: Sharon Austin, Professor of Political Science, University of Florida

Read more https://theconversation.com/before-kamala-harris-many-black-women-aimed-for-the-white-house-149729