Obstacles to voting: 6 essential reads on the challenges of election 2020

- Written by Catesby Holmes, International Editor and Politics Editor, The Conversation US

Plots to kidnap governors. White militias patrolling city streets. Partisan enmity that boils over into bar brawls. Disappearing ballot boxes. A hobbled mail system. Russian trolls. Oh, and a pandemic.

The U.S. has held elections in worse times than now – during the Civil War[1], for example – but this year brings daunting challenges to voting.

Here, academic experts describe five major threats to election 2020 – and one has tips to make sure your vote is counted anyway.

1. Pandemic-induced chaos

For an example of just how bad things could get this year, look at Georgia’s presidential primary election in June.

Because absentee ballots went undelivered and the election website crashed, some voters weren’t sure if they needed to vote in person, while others didn’t know where to vote. And with 10% of Georgia’s polling places closed due to COVID-19 restrictions and staffing shortages, lines grew exceptionally long, according to Adrienne Jones, who studies voter suppression at Morehouse College[2].

“Hundreds of voters, many in majority Black areas, waited up to seven hours to cast their ballots,” writes Jones. “Some even faced down police seeking to send them home without having voted.”

Some Georgia voting machines also broke on primary day.

Jones calls Georgia’s primary a “nightmare mix of inefficiency and discrimination” coupled with pandemic-related restrictions.

2. Protracted waits

Long lines in Texas’s March primary election forced officials in some places to extend voting hours to accommodate the crowd. But that helps only voters who can stick around for hours.

“Long wait times discourage people from voting,” writes Jonathan Coopersmith of Texas A&M University.

Milwaukee residents before voting in the state’s April 7 elections.

AP Photo/Morry Gash[3]

Milwaukee residents before voting in the state’s April 7 elections.

AP Photo/Morry Gash[3]

In the 2012 election, prolonged wait times prevented an estimated 500,000 to 700,000 out of 123 million American voters from casting their ballot. Most of them were “poorer people with less flexibility at work[4],” writes Coopersmith.

While a 2014 U.S. government report says that no citizen should wait more than 30 minutes to vote, there is no federal law governing wait times.

Expanding early voting and giving people paid time off to vote during the work day could reduce delays, writes Coopersmith, “so that someday no voter will have to wait more than 30 minutes to have their voice heard.”

3. Poll worker shortages

One big reason for long lines is staffing shortages. Voting in the U.S. is overseen by an army of civilians who check voters in, verify their identity, determine their eligibility, trouble-shoot technical problems and answer questions.

Poll work is a tough job that pays modestly. And that’s one reason these “gatekeepers of democracy” are generally older people, says Thessalia Merivaki, an expert on poll workers[5] at Mississippi State University.

“Most are retirees, who arguably have more free time on their hands,” she writes. “They also have a strong sense of civic duty.”

But many veteran poll workers are reluctant to serve in a pandemic because of their age, so local officials have been recruiting younger volunteers to staff roughly 230,000 polling sites in November. At least 350,000 people had volunteered as of early September, Merivaki finds. For perspective, 917,694 poll workers worked the 2016 presidential election.

These new recruits are younger and more diverse than regular poll workers, who are typically older white women, says Merivaki. That’s a positive change, since “minority voters report more positive experiences when they interact with poll workers who look like them.”

Voting tends to go more smoothly when poll workers reflect their community.

Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images[6]

Voting tends to go more smoothly when poll workers reflect their community.

Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images[6]

But the new recruits will also be inexperienced, which may lead to some problems on Election Day. Election officials provide training to new recruits, but Merivaki says “training is no match for years on the job.”

4. Voter intimidation

Alleging that election fraud was likely in November, Donald Trump has urged his supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully.”

To Rutgers University Newark history professor Mark Krasovic, the president seemed to be encouraging voter intimidation[7], a “practice long used in the U.S. by political parties to suppress one side’s vote and affect an election’s outcome.”

The GOP has historically made particular use of this electoral strategy, Krasner says.

In New Jersey’s 1981 governor’s race, some 200 armed, uniformed men patrolled polling sites, demanding voter ID cards from Black voters and chasing Latino voters away. The interference was so egregious that a court forbade Republicans nationwide from engaging in voter intimidation.

But that court order expired in 2018.

“The 2020 election will be the first in nearly 40 years conducted without the protections afforded by that decree,” writes Krasovic.

5. Russian hacking

For cybercrimes expert Douglas W. Jones, “we should be worried” about Russian cyberinterference in the 2020 U.S. election[8].

“Four years ago, Russia managed to penetrate systems in several states, but there’s no evidence that they ‘pulled the trigger’” to actually manipulate vote counts, he writes.

This year Russia may not hold back.

“My impression is that they’re getting better at disinformation campaigns,” writes Jones, adding: “I think it’s safe to assume that they’re also getting better at digging into the actual machinery of elections.”

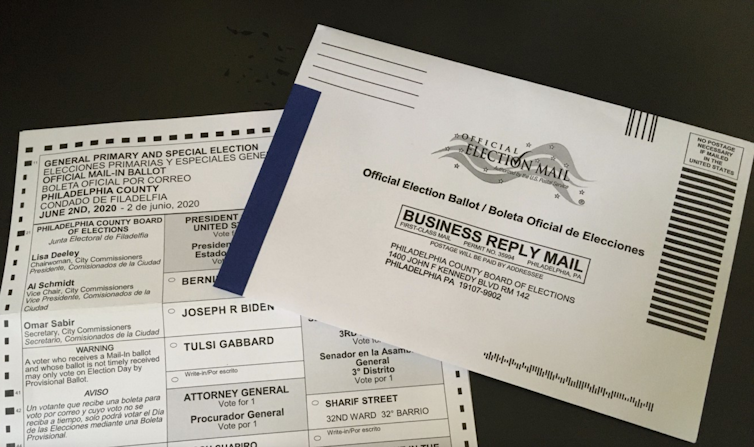

Mail-in voting is not more susceptible to fraud than voting in person.

WCN 24/7/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND[9][10]

Mail-in voting is not more susceptible to fraud than voting in person.

WCN 24/7/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND[9][10]

6. Get your vote counted anyway

That’s a lot of obstacles, but voters should not be deterred, says Amy Dacey of American University.

“Do not be intimidated or afraid,” she writes. “It is your right to vote. Exercise that right proudly and make your voice heard.”

Dacey offers tips to make sure that happens[11].

One is to make a voting plan, whether you’re casting your ballot by mail or in person. And track your ballot by mail, if possible. Set reminders to vote, too, just as you would for any other important event, writes Dacey.

Finally, tell your friends and family to vote, urges Dacey, because “every vote that is cast is a vital contribution to the nation’s future.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[12].]

References

- ^ during the Civil War (theconversation.com)

- ^ Adrienne Jones, who studies voter suppression at Morehouse College (theconversation.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Morry Gash (www.apimages.com)

- ^ poorer people with less flexibility at work (theconversation.com)

- ^ expert on poll workers (theconversation.com)

- ^ Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ the president seemed to be encouraging voter intimidation (theconversation.com)

- ^ “we should be worried” about Russian cyberinterference in the 2020 U.S. election (theconversation.com)

- ^ WCN 24/7/Flickr (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ tips to make sure that happens (theconversation.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Catesby Holmes, International Editor and Politics Editor, The Conversation US