From recording videos in a closet to Zoom meditating, 2020's political campaigns adjust to the pandemic

- Written by Barbara A. Trish, Professor of Political Science, Grinnell College

President Donald Trump may have eschewed masks and distancing in this pandemic year of campaigning, resulting in both his diagnosis of COVID-19 and the spread of the disease in the White House.

But others have figured out how to campaign with reduced risk. This cycle, there’s plenty of expertise, technology and ingenuity to go around.

I study campaign politics, and the book I’m co-authoring for Routledge – “Inside the Caucus Bubble” – includes a close look at campaign practices from the recent presidential nomination contest.

This is 2020, not 1828, when candidates had few paths to the voter beyond in-person contact and little support beyond[1] what the party organization offered.

The cast of characters in U.S. electoral politics extends well beyond voters and campaigns and includes vendors, consultants, data brokers, analytics professionals, media consultants and creative teams who all play a part in carrying out a campaign.

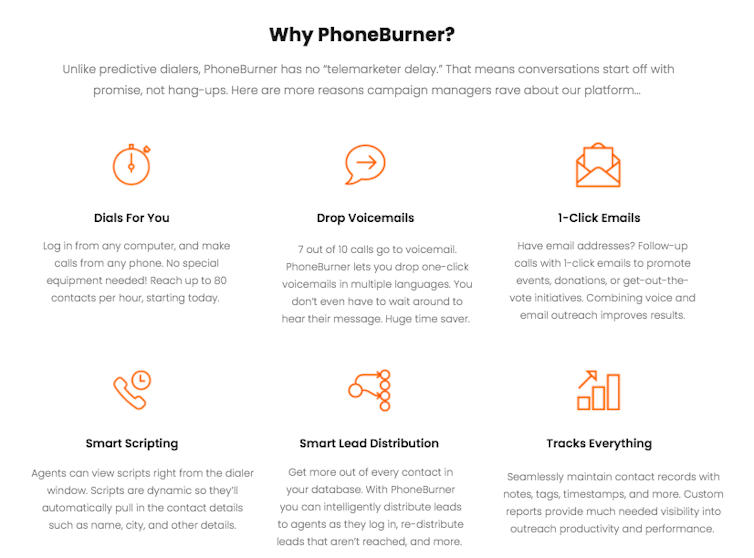

Marketing for PhoneBurner, whose tagline is ‘Political Dialing Made Easy.’

PhoneBurner[2]

Marketing for PhoneBurner, whose tagline is ‘Political Dialing Made Easy.’

PhoneBurner[2]

I’ve looked at the way campaigns engage voters and motivate volunteers and at vendors who offer a range of products and services, from digital fundraisers who run tests on email subject lines to old-school print shops, still producing yard signs.

Candidates, campaigns and the vendors they work with, I found, have been able to adjust and innovate in the COVID-19 era.

On the heels of active 2018 midterm contests and the recent Democratic presidential nomination race, the 2020 general election campaigns are generally well positioned to compete in this challenging new environment. For some, the spate of late spring and early summer primaries offered a trial run in campaigning during a pandemic.

Diffusing power

An infrastructure for remote organizing was already in place before the pandemic, facilitating communication among staff, volunteers and voters without any in-person contact.

Virtual phone banks[3] had been around for a few cycles, freeing campaigns from relying on a field office or a donated space like a law firm conference room, where volunteers would assemble to make calls. Instead, volunteers[4] – with apps on their mobile phones connecting them to lists, scripts and the ability to enter data – can make calls[5] wherever they are.

By 2018, campaigns began to rely on new platforms for texting to engage volunteers and voters. Known as peer-to-peer texting[6], these programs make campaign communications look a lot more like what voters receive from their friends on a daily basis, increasing the likelihood that they will read, respond and engage with the campaign.

Texting is a mainstay of “relational organizing,”[7] which puts the tools of organizing directly in the hands of field staff and volunteers. This ostensibly diffuses power within a campaign organization and untethers workers and volunteers from the physical connection to, and the control of, the campaign structure.

The 2020 Sanders and Buttigieg campaigns played up these qualities, with Buttigieg going further, introducing a design toolkit that allowed supporters to customize[8] their own digital and traditional campaign products such as T-shirts and yard signs.

Screenshot from the Pete Buttigieg design toolkit that allowed supporters to customize their own digital and campaign products such as T-shirts and yard signs.

Hyperakt[9]

Screenshot from the Pete Buttigieg design toolkit that allowed supporters to customize their own digital and campaign products such as T-shirts and yard signs.

Hyperakt[9]

Separating out the meaningful impact of tools like these from the hype associated with something new is always hard. At a minimum, the same technologies that campaigns have been using to spread tasks across an organization mesh well with a world in which face-to-face is less of an option.

The same is true of an event platform, Mobilize[10], that helps progressives manage events and recruit volunteers. This spring, Mobilize shifted abruptly from its prepandemic focus on in-person events to an all-virtual event world. Since then, Mobilize has added a new feature, delivering an automated request to a volunteer to host her own virtual event.

Putting tools directly in volunteer hands has the potential to bring unexpected voices into the campaign[11]. The Mobilize platform lists an early October “Meditation for Joe and Kamala”[12] Zoom-based event, hosted in Los Angeles, making this pitch to activists: “Meditate together for Joe and Kamala. All are welcome, no experience required:)”

Making videos in a closet

Much campaign work can be done from home. The jury-rigged home office of Michigan congressional candidate Hillary Scholten features an overturned laundry basket propped on her dryer[13]. The candidate finds this standing-desk setup, with campaign placards as backdrop, good for making calls to donors – and pairing socks at the same time.

For tasks that can’t be accomplished remotely, the obvious fix starts with pandemic safety measures. The in-person voter registration work of Mi Familia Vota[14] came to a halt when the pandemic hit. Now, the Latino vote-focused organization sends out volunteers, after a temperature check, equipped with bleach wipes, gloves and dozens of pens[15].

In midsummer, Campaigns and Elections Magazine[16], a leading trade publication for political campaign professionals, offered its first “at home” version of its campaign technology conference.

Vendors and consultants at the conference described an ever-changing 2020 political environment, heavily influenced by the status of the virus outbreak. Their work, they said, is subject to parameters set by lockdown terms and state regulations – sometimes in flux – about ballot access and early voting.

Digital apps, like this one for the Trump campaign, are an essential part of running a campaign.

Google.com[17]

Digital apps, like this one for the Trump campaign, are an essential part of running a campaign.

Google.com[17]

At that time, even elements of the digital landscape presumably immune to the pandemic were a moving target. Facebook had just announced an “opt out” feature[18] to turn off political ads. More recently, Facebook announced that it would ban political ads for the week preceding Nov. 3[19], joining other prominent social media platforms – Twitter and Google[20] – which have otherwise regulated political advertising.

The combined moves of these three giants undoubtedly affect how campaigns are run, though other social media paths to voters remain open.

Those who tuned in for the conference heard about innovations that were responsive to the current situation. Chris Bachman of SBDigital[21], a digital media agency, told about a client locked down in her home who needed to produce campaign videos. She recorded voice-overs in her closet, clothes absorbing sound to produce better audio on her iPhone.

Not all campaign innovations work well in the pandemic era. Digital consultant Cheryl Hori had orchestrated a creative use for Waze, the navigation software, in a prepandemic setting.

Hori, founder of Pacific Campaign House[22], placed Election Day targeted ads on Waze that popped up when a car came to a stop; they made the pitch to vote, then directed the driver to the nearest polling place. The ads wouldn’t be too useful in 2020, with fewer people voting in person and more by mail.

Meet voters where they are

Campaign insiders say the pandemic makes candidates’ authenticity that much more important. Ryanne Brown, an advertising executive with digital firm Do Big Things[23], put it this way: “People’s BS meters are on high alert.” The pandemic reinforces the adage that campaigns should “meet voters where they are.”

That may be a literal statement this year. A lot of those voters are at home; many are using internet-supported platforms that allow advertising.

For the political media professionals who navigate this world of what’s called “over the top” advertising, a pandemic is the perfect opportunity[24]. Campaigns have less competition for advertising space (think canceled Summer Olympics and locked-down travel destinations), and viewers have more time to watch streamed content.

Certainly not all campaigns are positioned to – or want to – take advantage of the high-tech tools and resources of the industry. An Iowa legislative candidate’s Zoom mojito fundraiser involved low-tech aspects as well: a doorstop delivery of a small mint plant – no contact – with a home printer-produced label, “Vote Sarah Smith for HD76.”

Generally speaking, despite extraordinary circumstances and developments, the conduct of this campaign should look familiar to the 21st-century observer – just with some adjustments.

[Get our most insightful politics and election stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly[25].]

References

- ^ few paths to the voter beyond in-person contact and little support beyond (global.oup.com)

- ^ PhoneBurner (get.phoneburner.com)

- ^ Virtual phone banks (www.technologyreview.com)

- ^ Instead, volunteers (swingleft.org)

- ^ can make calls (www.cagop.org)

- ^ peer-to-peer texting (www.npr.org)

- ^ Texting is a mainstay of “relational organizing,” (www.wired.com)

- ^ a design toolkit that allowed supporters to customize (mashable.com)

- ^ Hyperakt (pete.hyperakt.com)

- ^ Mobilize (www.mobilize.us)

- ^ unexpected voices into the campaign (www.campaignsandelections.com)

- ^ “Meditation for Joe and Kamala” (www.mobilize.us)

- ^ laundry basket propped on her dryer (www.wsj.com)

- ^ Mi Familia Vota (www.mifamiliavota.org)

- ^ equipped with bleach wipes, gloves and dozens of pens (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Campaigns and Elections Magazine (www.campaignsandelections.com)

- ^ Google.com (play.google.com)

- ^ Facebook had just announced an “opt out” feature (techcrunch.com)

- ^ ban political ads for the week preceding Nov. 3 (www.politico.com)

- ^ Twitter and Google (www.wsj.com)

- ^ Chris Bachman of SBDigital (www.sbdigital.com)

- ^ Hori, founder of Pacific Campaign House (www.pacificcampaignhouse.com)

- ^ Ryanne Brown, an advertising executive with digital firm Do Big Things (dobigthings.today)

- ^ the perfect opportunity (www.rbr.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly (theconversation.com)

Authors: Barbara A. Trish, Professor of Political Science, Grinnell College