A proposed mine threatens Minnesota's Boundary Waters, the most popular wilderness in the US

- Written by Char Miller, W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis and History, Pomona College

President Trump has worked aggressively to dismantle the environmental legacy[1] of his predecessor Barack Obama since taking office in 2017. The latest example is a mining project that could affect the most heavily visited wilderness area in the United States: the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness[2], which stretches over a million acres in the Superior National Forest[3] in remote northern Minnesota.

This bucket-list destination for paddling, fishing and camping[4] contains more than 1,200 miles of canoe routes among thousands of lakes and streams, drawing some 250,000 visitors yearly. Just to its southwest are large metal deposits – part of Minnesota’s Iron Ranges, which have been a major mining region since the mid-1800s[5].

For over a decade[6] a company called Twin Metals[7] has been seeking permission to build and run an underground copper, nickel, cobalt and platinum mine there. Opponents, including local residents, conservation groups and outdoor businesses, argue that this operation could release toxic contaminants[8] that would wash into the Boundary Waters and adjoining parks, poisoning wildlife and contaminating soils.

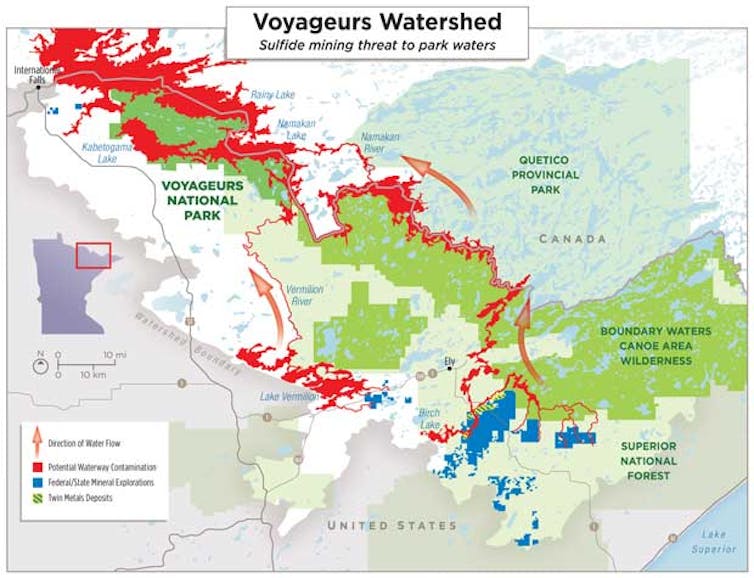

Critics of the Twin Metals mine proposal argue that pollution from sulfide-ore copper mining could flow into the Boundary Waters, and from there into Voyageurs National Park and Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park.

Voyageurs National Park Association, CC BY-ND[9][10]

Critics of the Twin Metals mine proposal argue that pollution from sulfide-ore copper mining could flow into the Boundary Waters, and from there into Voyageurs National Park and Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park.

Voyageurs National Park Association, CC BY-ND[9][10]

The Obama administration opposed the project and declined to renew expiring leases for Twin Metals in 2016. But the Trump administration granted new leases[11] in May 2019. As a scholar who studies public land management[12], I see this controversy as a classic debate over environmental protection versus job creation, with a twist: There’s a compelling economic argument for conservation.

Short- and long-term benefits

U.S. national forests are managed with multiple uses in mind, including logging, livestock grazing, biodiversity, air and water quality and recreation. Designating part of a national forest as wilderness is a big step that prohibits some of those uses. It means, in the language of the 1964 Wilderness Act[13], that “there shall be no commercial enterprise and no permanent road within any wilderness area,” nor any motorized vehicles that would mar the land’s “primeval character,” its “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation.”

The Boundary Waters first received protection as a roadless wilderness area in 1926[14] at the recommendation of the Forest Service’s first landscape architect, Arthur Carhart. “There is one outstanding feature found in the Superior National Forest which is not present in any other nationally owned property,” Carhart asserted. “This is a lake type of recreation. The Superior is unquestionably one of the few great canoe countries of the world[15].”

Lynda Bird Johnson, daughter of president Lyndon Johnson, on a visit to the Boundary Waters in 1965.

USFS/Flickr, CC BY[16][17]

Lynda Bird Johnson, daughter of president Lyndon Johnson, on a visit to the Boundary Waters in 1965.

USFS/Flickr, CC BY[16][17]

This was just the second officially protected U.S. wilderness area[18] at the time. Today Northeast Minnesota’s outdoor recreation economy generates more than US$900 million in annual revenues and sustains over 17,000 jobs[19].

A 2016 study estimated that the Boundary Waters alone accounts for 1,000 jobs and $77 million in annual economic output[20]. “Outdoor recreation is an export industry for northeastern Minnesota, providing for stable employment and sustainable jobs year after year,” the report observed.

For comparison, Twin Metals projects that its mine would operate for 25 years[21] and generate more than 2,250 jobs[22]. A Harvard economist who assessed these two options in 2018 concluded that over 20 years, protecting the Boundary Waters would provide greater economic benefits than approving the mine[23].

Critics of the proposed mine are worried because mining generates large quantities of waste rock. Metals in these rocks can produce highly acidic runoff that pollutes rivers, streams and groundwater[24].

A 2012 study of 15 U.S. sulfide-ore copper mines, published by the environmental advocacy organization Earthworks, found that 14 of the projects experienced accidental releases that resulted in significant water contamination[25]. Since the Boundary Waters exists within a vast network of interconnected lakes and streams, toxic mining pollution upstream could be disastrous for fish, wildlife and wilderness values.

Polls show that an overwhelming majority of Minnesotans, including residents of the northern counties, want to protect the Boundary Waters[26] and the jobs and revenues that the wilderness generates. On the other side, unions, business organizations and local elected officials[27] argue that the mine will boost the regional economy[28] while producing “strategic minerals critical to the transition to a green economy and our national security.”

Follow a family paddling, camping and fishing in the Boundary Waters.Fast-tracking development

As often is true of mining proposals, several agencies are involved. The Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management controls all minerals on U.S. public lands. Because 400 acres of the proposed mine’s 1,156-acre footprint is within the Superior National Forest[29], the bureau needs the Forest Service’s consent[30] to approve the project.

In 2016, after analyzing the mine’s potential impacts, the Forest Service refused to consent to the lease, and the Obama administration imposed a 20-year moratorium on mining near the Boundary Waters. But things changed a year later, shortly after President Trump’s inauguration, when his daughter Ivanka Trump and her husband Jared Kushner rented a District of Columbia mansion from a Chilean businessman named Andrónico Luksic[31].

[Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get expert takes on today’s news, every day.[32]]

Luksic was the chief executive officer of Antofagasta, a Chilean conglomerate that owned Twin Metals. Within weeks, senior U.S. officials were meeting with Antofagasta leaders and reexamining the leases. Company representatives and a spokesperson for the Kushners said there was no link between the rental and action on the mine[33], but ethics experts said even the appearance of a conflict[34] was troubling.

Administration officials have sought to weaken the Forest Service’s authority over mineral leases[35] across its 193 million acres of national forests and grasslands. On June 12, Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, whose agency includes the Forest Service, issued a memo that directed the Forest Service to “streamline processes and identify new opportunities to increase America’s energy dominance and reduce reliance on foreign countries for critical minerals[36].” And the agency has signaled its willingness to do so.

Ecological value

Trump has claimed credit on the campaign trail for saving Minnesota’s mining economy from stifling environmental regulation. “Our miners are back on the job and wages have increased by as much as 50%…. But if Biden wins the Iron Range we’ll be shut down forever, you know that,” he told an audience in Mankato, Minnesota[37], on Aug. 17.

Ironically, just a few days later the Trump administration hit the pause button[38] on another large mining project: the proposed Pebble Mine in Alaska, which critics assert would pollute Bristol Bay[39], the site of several lucrative wild salmon fisheries. The administration reportedly reversed course after Donald Trump Jr. and other prominent conservatives who are avid hunters and anglers[40] objected to it.

While jobs and economic impacts loom large in this debate, they aren’t the only issues at stake. At an international biodiversity summit[41] on Sept. 30, United Nations officials issued a call to action to protect nature from degradation. With biodiversity declining “at rates unprecedented in human history, with growing impacts on people and our planet,” they specifically pointed out that some 85% of global wetlands have been lost to development, with 35% of that total[42] disappearing between 1970 and 2015.

That makes the Boundary Waters, with its 1,000 glacier-gouged lakes, both a relic and an opportunity for Minnesotans, Americans and the planet.

References

- ^ dismantle the environmental legacy (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (www.fs.usda.gov)

- ^ Superior National Forest (www.fs.usda.gov)

- ^ bucket-list destination for paddling, fishing and camping (www.fieldandstream.com)

- ^ since the mid-1800s (www.minnpost.com)

- ^ over a decade (www.twin-metals.com)

- ^ Twin Metals (www.twin-metals.com)

- ^ release toxic contaminants (www.savetheboundarywaters.org)

- ^ Voyageurs National Park Association (www.voyageurs.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ granted new leases (www.minnpost.com)

- ^ studies public land management (www.rizzoliusa.com)

- ^ Wilderness Act (www.fs.usda.gov)

- ^ 1926 (www.house.leg.state.mn.us)

- ^ one of the few great canoe countries of the world (apnews.com)

- ^ USFS/Flickr (flic.kr)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ second officially protected U.S. wilderness area (bwca.cc)

- ^ US$900 million in annual revenues and sustains over 17,000 jobs (mn.gov)

- ^ 1,000 jobs and $77 million in annual economic output (recpro.memberclicks.net)

- ^ operate for 25 years (www.twin-metals.com)

- ^ generate more than 2,250 jobs (www.twin-metals.com)

- ^ greater economic benefits than approving the mine (scholar.harvard.edu)

- ^ pollutes rivers, streams and groundwater (theconversation.com)

- ^ significant water contamination (www.earthworks.org)

- ^ protect the Boundary Waters (www.startribune.com)

- ^ local elected officials (www.mprnews.org)

- ^ boost the regional economy (jobsforminnesotans.org)

- ^ within the Superior National Forest (www.federalregister.gov)

- ^ needs the Forest Service’s consent (apnews.com)

- ^ Chilean businessman named Andrónico Luksic (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get expert takes on today’s news, every day. (theconversation.com)

- ^ no link between the rental and action on the mine (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ appearance of a conflict (www.wsj.com)

- ^ authority over mineral leases (www.federalregister.gov)

- ^ reduce reliance on foreign countries for critical minerals (news.bloomberglaw.com)

- ^ audience in Mankato, Minnesota (www.fox21online.com)

- ^ hit the pause button (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ pollute Bristol Bay (www.savebristolbay.org)

- ^ avid hunters and anglers (www.sciencemag.org)

- ^ international biodiversity summit (www.un.org)

- ^ 35% of that total (www.unwater.org)

Authors: Char Miller, W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis and History, Pomona College