Feminist activists today should still look to 'Our Bodies, Ourselves'

- Written by Sara Hayden, Professor of Communication Studies, The University of Montana

In April 2018, the Our Bodies, Ourselves collective, the group responsible for publishing the book of the same name, decided to stop offering new editions[1] of its groundbreaking text.

“Our Bodies, Ourselves” has been remarkably successful. It has sold more than 4 million copies and been translated into 31 languages. In 2011, Time magazine[2] recognized “Our Bodies, Ourselves” as one of the best 100 nonfiction books published in English since 1923. In 2012, the Library of Congress included it[3] in its “Books that Shaped America” exhibition.

I first became interested in the collective when I was in graduate school[4], and I revisit the rhetoric of the group in an upcoming article in the Quarterly Journal of Speech.

From years of studying the group, I’ve come to believe that although the book is no longer being updated, it nonetheless provides a useful model for contemporary feminist activism[5] – and could possibly alleviate some of the conflicts that continue to roil today’s feminist movements.

Feminist roots

The women who wrote the first edition of “Our Bodies, Ourselves” met at a women’s liberation conference in 1969.

They had gathered to discuss the topic of women and their bodies, but it didn’t take them long to realize they knew little about their health, sexuality or reproduction. Their subsequent efforts to find this information were unsuccessful. Even physicians were unwilling to answer their questions on issues ranging from childbirth to birth control.

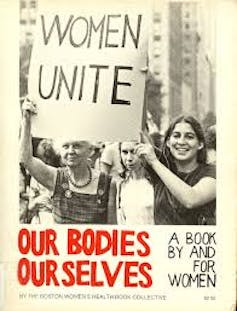

The cover of the 1973 edition of ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves.’

'Our Bodies Ourselves'[6]

The cover of the 1973 edition of ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves.’

'Our Bodies Ourselves'[6]

A handful of women decided to take matters into their own hands. They borrowed library cards from medical students, snuck into medical libraries and wrote up what they learned in a series of papers. They included information important to their lives, including anatomy and physiology, sexuality, abortion, pregnancy and prepared childbirth.

The authors shared their papers with one another, and, through the process, they realized the information became even more relevant when presented alongside their personal experiences[7].

When discussing menstruation, for example, they realized that they had been taught the basics in school, but the material never really stuck. Once they discussed the topic in terms of their personal experiences, such as how they felt about their first periods, the information became much more meaningful.

The women were interested in sharing this information with others, so they decided to publish their papers, along with their personal reflections, as a book. First called “Women and their Bodies,” in 1971, the group changed the book’s title to “Our Bodies, Ourselves[8].”

Updated every four to six years, the collective published the ninth and final edition in 2011.

Facing up to challenges

In spite of the collective’s successes, the group has experienced its share of problems. In its early years, the group struggled to offer suggestions and guidance while also acknowledging that not all women’s experiences or beliefs are the same.

In the 1984 edition, for example, they included a note[9] indicating that they chose not to discuss pornography “primarily because we disagree with one another and/or have not come to any clear positions yet on some crucial issues.” They continued: “We recognize that some of us will find offensive what others view as erotica, and vice versa… But this need not keep us from speaking out against what we believe is degrading to women and, ultimately, everyone.”

A recognition of this – and other – differences led to debates over strategies and goals.

Yet unlike other feminist groups that were torn apart by such issues, the collective prospered for close to 50 years[10].

An inclusive model for feminist activism

The group’s success can be attributed to the model of feminist activism they illustrate in their book.

Based in consciousness-raising, it is a model that prompts women to explore issues in the context of their personal experiences, the experiences of others and the best factual knowledge available to them. As they revised the book, the collective incorporated the voices of more and more women, and they urged their readers to consider the issues being discussed in terms of their own lives.

In early editions of the book, the collective focused on women’s health and reproduction. As they updated and rewrote the book, they expanded their coverage to include body image, agriculture and food businesses, environmental and occupational health, and violence against women, among other topics.

The authors discussed these issues in a feminist political context. And, they explained how they and others responded to the problems they unearthed.

Importantly, though, the collective did not direct their readers to a particular course of action.

Recognizing that women’s experiences differed, they offered readers guidelines for finding other women who shared their concerns. In addition, they offered a series of questions designed to help women determine the actions they might want to take.

In the 1996 edition, for example, they ask their readers to consider[11]: “Are the women most affected centrally involved in efforts to create solutions?” They add: “Will our work give women a sense of power? Will our work help inform the public and motivate it to work for more improvements in women’s health?”

Most significantly, the collective urged readers to seek out and listen to the voices of women from different backgrounds and circumstances. They included such voices in the pages of their book.

Making the world a better place

“Our Bodies, Ourselves” doesn’t offer a simple, consistent message – there is no prescriptive dogma.

In fact, there are many places where the collective acknowledges that expert opinions vary. The range of testimonies included in the book illustrate the diverse ways women have responded to similar problems, whether it’s dealing with a cancer diagnosis or trying to eliminate health hazards in the workplace.

What “Our Bodies, Ourselves” does offer is a model for taking action in the face of diversity and uncertainty[12].

Contemporary feminists are facing many of the same challenges their predecessors faced. Whether addressing the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual assault uncovered by the #MeToo movement[13] or determining the next steps to take in the wake of the women’s marches[14], feminists struggle over strategies and goals.

Many of these struggles reflect differences based in race[15], age[16] and even geographic location[17].

Organizers of the original Women’s March on Washington, for example, are focused on social justice protests. Another group of activists who participated in the women’s marches believe that social justice protests will not be well-received in red states. They want to turn the energy of the women’s marches toward electoral politics[18].

What “Our Bodies, Ourselves” teaches is that there is no one correct course of action. Women differ from one another, and various experiences will lead to a range of priorities and goals. This is okay – and it probably has the best chance to make the world a better place.

References

- ^ new editions (www.npr.org)

- ^ Time magazine (www.ourbodiesourselves.org)

- ^ included it (www.ourbodiesourselves.org)

- ^ graduate school (search-proquest-com.weblib.lib.umt.edu)

- ^ contemporary feminist activism (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ 'Our Bodies Ourselves' (www.ourbodiesourselves.org)

- ^ personal experiences (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ Our Bodies, Ourselves (www.ourbodiesourselves.org)

- ^ they included a note (books.google.com)

- ^ 50 years (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ they ask their readers to consider (books.google.com)

- ^ uncertainty (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ #MeToo movement (www.vox.com)

- ^ women’s marches (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ race (moneyish.com)

- ^ age (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ geographic location (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ toward electoral politics (www.nytimes.com)

Authors: Sara Hayden, Professor of Communication Studies, The University of Montana

Read more http://theconversation.com/feminist-activists-today-should-still-look-to-our-bodies-ourselves-95503