Protecting half of the planet is the best way to fight climate change and biodiversity loss – we've mapped the key places to do it

- Written by Greg Asner, Director, Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science and Professor, Arizona State University

Humans are dismantling and disrupting natural ecosystems around the globe and changing Earth’s climate. Over the past 50 years, actions like farming, logging, hunting, development and global commerce have caused record losses of species[1] on land and at sea. Animals, birds and reptiles are disappearing tens to hundreds of times faster than the natural rate of extinction over the past 10 million years.

Now the world is also contending with a global pandemic. In geographically remote regions such as the Brazilian Amazon, COVID-19 is devastating Indigenous populations, with tragic consequences[2] for both Indigenous peoples and the lands they steward.

My research[3] focuses on ecosystems and climate change from regional to global scales. In 2019, I worked with conservation biologist and strategist Eric Dinerstein[4] and 17 colleagues to develop a road map for simultaneously averting a sixth mass extinction and reducing climate change by protecting half of Earth’s terrestrial, freshwater and marine realms by 2030. We called this plan “A Global Deal for Nature[5].”

Now we’ve released a follow-on called the “Global Safety Net[6]” that identifies the exact regions on land that must be protected to achieve its goals. Our aim is for nations to pair it with the Paris Climate Agreement[7] and use it as a dynamic tool to assess progress towards our comprehensive conservation targets.

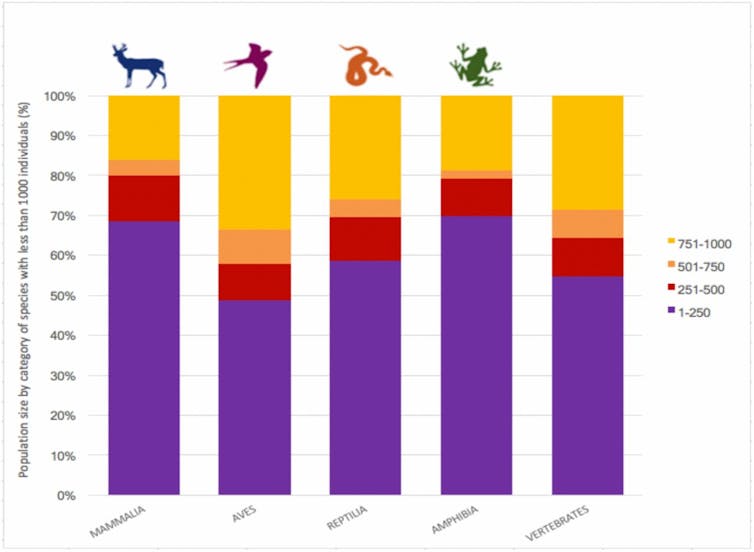

Population size of terrestrial vertebrate species on the brink (i.e., with under 1,000 individuals). Most of these species are especially close to extinction because they consist of fewer than 250 individuals. In most cases, those few individuals are scattered through several small populations.

Ceballos et al, 2020., CC BY[8][9]

Population size of terrestrial vertebrate species on the brink (i.e., with under 1,000 individuals). Most of these species are especially close to extinction because they consist of fewer than 250 individuals. In most cases, those few individuals are scattered through several small populations.

Ceballos et al, 2020., CC BY[8][9]

What to protect next

The Global Deal for Nature provided a framework for the milestones, targets and policies across terrestrial, freshwater and marine realms required to conserve the vast majority of life on Earth. Yet it didn’t specify where exactly these safeguards were needed. That’s where the new Global Safety Net comes in.

We analyzed unprotected terrestrial areas that, if protected, could sequester carbon and conserve biodiversity as effectively as the 15% of terrestrial areas that are currently protected. Through this analysis, we identified an additional 35% of unprotected lands for conservation, bringing the total percentage of protected nature to 50%.

By setting aside half of Earth’s lands for nature, nations can save our planet’s rich biodiversity, prevent future pandemics and meet the Paris climate target of keeping warming in this century below less than 2.7 degrees F (1.5 degrees C). To meet these goals, 20 countries must contribute disproportionately. Much of the responsibility falls to Russia, the U.S., Brazil, Indonesia, Canada, Australia and China. Why? Because these countries contain massive tracts of land needed to reach the dual goals of reducing climate change and saving biodiversity.

Supporting Indigenous communities

Indigenous peoples make up less than 5% of the total human population, yet they manage or have tenure rights over a quarter of the world’s land surface[10], representing close to 80% of our planet’s biodiversity. One of our key findings is that 37% of the proposed lands for increased protection overlap with Indigenous lands.

As the world edges closer towards a sixth mass extinction[11], Indigenous communities stand to lose the most. Forest loss, ecotourism and devastation wrought by climate change have already displaced Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories at unprecedented rates. Now one of the deadliest pandemics in recent history poses an even graver additional threat[12] to Indigenous lives and livelihoods.

To address and alleviate human rights questions, social justice issues and conservation challenges, the Global Safety Net calls for better protection for Indigenous communities. We believe our goals are achievable by upholding existing land tenure rights, addressing Indigenous land claims, and carrying out supportive ecological management programs with indigenous peoples.

Preventing future pandemics

Tropical deforestation increases forest edges – areas where forests meet human habitats. These areas greatly increase the potential for contact between humans and animal vectors that serve as viral hosts.

For instance, the latest research shows that the SARS-CoV-2 virus originated and evolved naturally in horseshoe bats[13], most likely incubated in pangolins[14], and then spread to humans via the wildlife trade[15].

The Global Safety Net’s policy milestones and targets would reduce the illegal wildlife trade and associated wildlife markets[16] – two known sources of zoonotic diseases. Reducing contact zones between animals and humans can decrease the chances of future zoonotic spillovers from occurring.

Our framework also envisions the creation of a Pandemic Prevention Program, which would increase protections for natural habitats at high risk for human-animal interactions. Protecting wildlife in these areas could also reduce the potential for more catastrophic outbreaks.

Nature-based solutions

Achieving the Global Safety Net’s goals will require nature-based solutions – strategies that protect, manage and restore natural or modified ecosystems while providing co-benefits to both people and nature. They are low-cost and readily available today.

The nature-based solutions that we spotlight include: - Identifying biodiverse non-agricultural lands, particularly prevalent in tropical and sub-tropical regions, for increased conservation attention. - Prioritizing ecoregions that optimize carbon storage and drawdown, such as the Amazon and Congo basins. - Aiding species movement and adaptation across ecosystems by creating a comprehensive system of wildlife and climate corridors[17].

We estimate that an increase of just 2.3% more land in the right places could save our planet’s rarest plant and animal species within five years.

Wildlife corridors connect fragmented wild spaces, providing wild animals the space they need to survive.Leveraging technology for conservation

In the Global Safety Net study, we identified 50 ecoregions where additional conservation attention is most needed to meet the Global Deal for Nature’s targets, and 20 countries that must assume greater responsibility for protecting critical places. We mapped an additional 35% of terrestrial lands that play a critical role in reversing biodiversity loss, enhancing natural carbon removal and preventing further greenhouse gas emissions from land conversion.

But as climate change accelerates, it may scramble those priorities. Staying ahead of the game will require a satellite-driven monitoring system with the capability of tracking real-time land use changes on a global scale. These continuously updated maps would enable dynamic analyses to help sharpen conservation planning and help decision-making.

As director of the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science[18], I lead the development of new technologies that assess and monitor imminent ecological threats, such as coral reef bleaching events[19] and illegal deforestation[20], as well as progress made toward responding to ecological emergencies. Along with colleagues from other research institutions who are advancing this kind of research, I’m confident that it is possible to develop a global nature monitoring program.

The Global Safety Net pinpoints locations around the globe that must be protected to slow climate change and species loss. And the science shows that there is no time to lose.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[21].]

References

- ^ record losses of species (ipbes.net)

- ^ tragic consequences (doi.org)

- ^ My research (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Eric Dinerstein (scholar.google.com)

- ^ A Global Deal for Nature (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Global Safety Net (advances.sciencemag.org)

- ^ Paris Climate Agreement (unfccc.int)

- ^ Ceballos et al, 2020. (www.pnas.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ over a quarter of the world’s land surface (doi.org)

- ^ sixth mass extinction (theconversation.com)

- ^ even graver additional threat (theconversation.com)

- ^ originated and evolved naturally in horseshoe bats (doi.org)

- ^ incubated in pangolins (dx.doi.org)

- ^ via the wildlife trade (dx.doi.org)

- ^ illegal wildlife trade and associated wildlife markets (theconversation.com)

- ^ wildlife and climate corridors (theconversation.com)

- ^ Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (gdcs.asu.edu)

- ^ coral reef bleaching events (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ illegal deforestation (news.mongabay.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Greg Asner, Director, Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science and Professor, Arizona State University