Trump greenlights drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, but will oil companies show up?

- Written by Scott L. Montgomery, Lecturer, Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington

The Trump administration has announced that it is opening up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge[1] to oil and gas development – the latest twist in a decades-long battle over the fate of this remote area. Its timing is truly terrible.

Low oil prices, a pandemic-driven recession and looming elections add up to highly unfavorable conditions for launching expensive drilling operations. In the longer term, the climate crisis and an ongoing shift to a lower-carbon economy raise big questions about future oil demand.

I’ve researched the U.S. energy industry[2] for more than 20 years. As I see it, conservative Republicans have backed oil and gas production in ANWR since the 1980s for two overriding reasons. First, to increase domestic oil production and reduce dependence on “foreign oil,” a euphemism for imports from OPEC countries. This argument now is largely dead, thanks to the fracking revolution[3], which has greatly expanded U.S. oil and gas production.

The other motive for drilling in ANWR, I believe, is to score a major, precedent-setting victory over government policies that prioritize conservation over energy production and environmental advocacy groups that have fought for years to protect ANWR as “one of the finest examples of wilderness left on Earth[4].” Capturing ANWR and transforming it into a locus of fossil fuel extraction would be a massive physical and symbolic triumph for politicians who believe that resource extraction is the highest use of public lands[5].

President Trump seems to understand this, based on his recent comment that “ANWR is a big deal that Ronald Reagan couldn’t get done and nobody could get done[6].” But global, national and oil industry circumstances are overwhelmingly arrayed against Trump getting it done.

An overview of 40 years of controversy over drilling in ANWR.Years of debate

ANWR is inarguably an ecological treasure. With 45 species of mammals and over 200 species of birds from six continents, the refuge is more biodiverse[7] than almost any area in the Arctic.

This is especially true of the 1002 coastal plain portion[8], which has the largest number of polar bear dens in Alaska. It also supports muskoxen[9], Arctic wolves, foxes, hares, migrating waterfowl and Porcupine caribou, which calve there. Most of ANWR is designated as wilderness, which puts it off-limits for development. But this does not include the 1002 Area[10], which was recognized as a promising area for energy development when the refuge was created in 1980 and left that way after a 1987 study confirmed its potential.

Climate change is causing especially rapid warming in the Arctic[11], with probable negative effects for many of these species. Environmental advocates argue that fossil fuel production in ANWR will add to this process[12], damaging habitat and impacting the Indigenous people who rely on the wildlife[13] for subsistence. But the situation is complex: There are also Indigenous groups who support ANWR development[14] for the jobs and income it would bring.

Energy companies’ interest in ANWR, meanwhile, has risen and fallen over time. The discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay[15] in 1968, followed by two oil shocks in the 1970s[16], sparked support for exploration and production in the region. But this enthusiasm faded in the late 1980s and ‘90s in the face of fierce political and legal opposition and years of low oil prices.

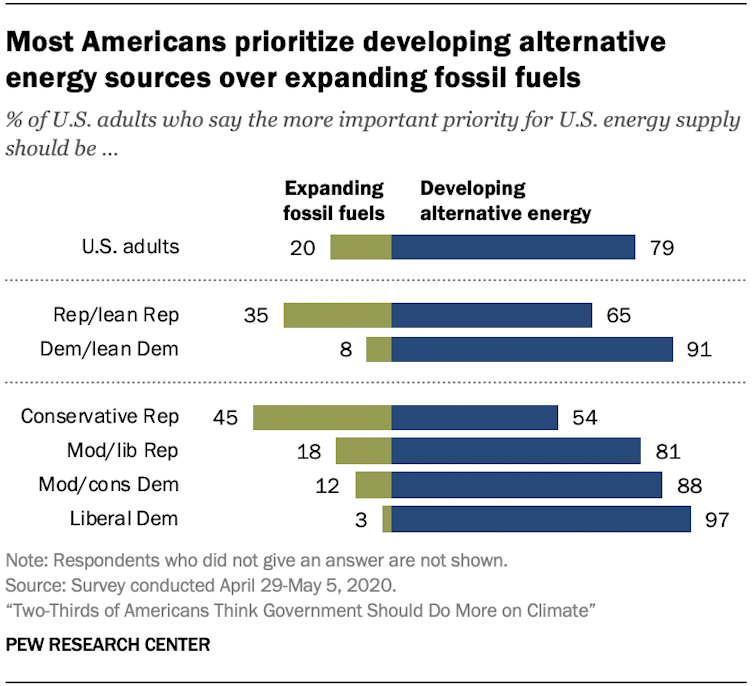

A majority of Americas of all political leanings believe the U.S. should develop alternative energy sources rather than expanding production of oil, coal and natural gas. Pew Research Center, CC BY-ND[17][18]

A majority of Americas of all political leanings believe the U.S. should develop alternative energy sources rather than expanding production of oil, coal and natural gas. Pew Research Center, CC BY-ND[17][18]

Scientists performed two major assessments of oil reserves in the 1002 Area in 1987[19] and 1998[20]. The latter study concluded that ANWR contained up to 11 billion barrels of oil that could be profitably recovered if prices were consistently high. But when prices rose between 2010 and late 2014, companies chose to focus instead on areas to the west of the refuge, where new discoveries had been made.

In the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017[21], a Republican-controlled Congress directed the Trump administration to open the 1002 Area to leasing. The bill required one lease sale within four years, and at least two sales within a decade. But as the Interior Department tried to comply, it was hampered by political controversies[22] and environmental assessment requirements.

The new Record of Decision[23], released on Aug. 17, 2020, determines where and how leasing will occur. It represents the Trump administration’s last chance to bring forward a well-designed leasing plan, and is certain to spark legal challenges[24] from environmental and wildlife organizations.

Is ANWR oil worth it?

Toady the oil industry is facing its greatest set of challenges in modern history. They include:

-

A collapse in oil demand and prices due to the global pandemic, with a sluggish and uncertain recovery[25]

-

Companies canceling and reducing activity worldwide, with bankruptcies in the U.S. shale industry and drilling rig counts[26] falling back to 1940 levels

-

New uncertainty about future global oil demand as climate concerns push public interest and government policy toward electric vehicles, and automakers respond with new EV designs

-

The growing possibility of Democratic victories in the November 2020 elections, which would likely lead to policies reducing fossil fuel use

-

Increasing investor pressure[27] on banks and investment firms to reduce or eliminate support for fossil fuel projects.

All of these factors compound the challenges of leasing and drilling in ANWR. Well costs there would be among the highest anywhere onshore in the U.S. Only one well has ever been drilled in the area, so new drilling would be purely exploratory and have a lower chance of success than in better-studied areas. Under these conditions, it would make more sense for companies that are active on Alaska’s North Slope to pursue sites they currently have under lease, which pose much lower risk.

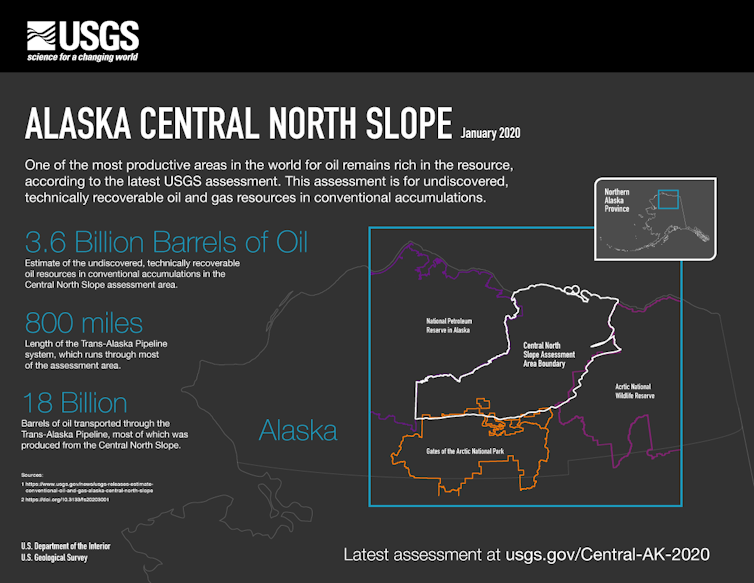

Alaska’s North Slope outside of ANWR remains rich in oil, according to the latest U.S. Geological Survey assessment. USGS[28]

Alaska’s North Slope outside of ANWR remains rich in oil, according to the latest U.S. Geological Survey assessment. USGS[28]

What’s more, as I have argued previously[29], it’s not clear that there’s a need to drill in ANWR. Energy companies have made new discoveries elsewhere south and west of Prudhoe Bay – most recently, the Talitha Field[30], which could yield 500 million barrels or more.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[31].]

Companies that pursue leases in ANWR also will have to weigh the prospects of litigation, investor anger and a tarnished brand – especially large firms with public name recognition. Shell’s experience in 2015, when it abandoned plans to drill offshore in the Arctic[32] under heavy pressure, indicate what other companies can expect.

If Trump is voted out of office, I expect that a Biden administration would quickly move to reverse[33] the directive for leasing in ANWR. In my view, this contested area will have far more meaning and value as a wildlife refuge in a warming world that is starting to seriously move away from hydrocarbon energy.

This is an updated version of an article[34] originally published on Dec. 20, 2017.

References

- ^ opening up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ researched the U.S. energy industry (scholar.google.com)

- ^ fracking revolution (www.marketwatch.com)

- ^ one of the finest examples of wilderness left on Earth (www.wilderness.org)

- ^ highest use of public lands (theconversation.com)

- ^ ANWR is a big deal that Ronald Reagan couldn’t get done and nobody could get done (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ is more biodiverse (www.amnh.org)

- ^ coastal plain portion (www.fws.gov)

- ^ muskoxen (theconversation.com)

- ^ does not include the 1002 Area (fas.org)

- ^ especially rapid warming in the Arctic (theconversation.com)

- ^ add to this process (www.nrdc.org)

- ^ Indigenous people who rely on the wildlife (www.alaskapublic.org)

- ^ Indigenous groups who support ANWR development (www.ktoo.org)

- ^ Prudhoe Bay (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ two oil shocks in the 1970s (www.cfr.org)

- ^ Pew Research Center (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ 1987 (dggs.alaska.gov)

- ^ 1998 (pubs.usgs.gov)

- ^ Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (www.congress.gov)

- ^ political controversies (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ new Record of Decision (www.doi.gov)

- ^ to spark legal challenges (www.arctictoday.com)

- ^ uncertain recovery (www.iea.org)

- ^ drilling rig counts (energynow.com)

- ^ investor pressure (www.reuters.com)

- ^ USGS (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ argued previously (theconversation.com)

- ^ Talitha Field (www.rigzone.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ abandoned plans to drill offshore in the Arctic (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ reverse (yaleclimateconnections.org)

- ^ article (theconversation.com)

Authors: Scott L. Montgomery, Lecturer, Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington