A rush is on to mine the deep seabed, with effects on ocean life that aren't well understood

- Written by Elizabeth M. De Santo, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, Franklin & Marshall College

Mining the ocean floor for submerged minerals is a little-known, experimental industry. But soon it will take place on the deep seabed, which belongs to everyone[1], according to international law.

Seabed mining for valuable materials like copper, zinc and lithium already takes place within countries’ marine territories[2]. As soon as 2025[3], larger projects could start in international waters – areas more than 200 nautical miles from shore, beyond national jurisdictions.

We study ocean policy[4], marine resource management[5], international ocean governance[6] and environmental regimes[7], and are researching political processes that govern deep seabed mining[8]. Our main interests are the environmental impacts of seabed mining, ways of sharing marine resources equitably[9] and the use of tools like marine protected areas[10] to protect rare, vulnerable and fragile species and ecosystems.

Today countries are working together on rules for seabed mining. In our opinion, there is still time to develop a framework that will enable nations to share resources and prevent permanent damage to the deep sea. But that will happen only if countries are willing to cooperate and make sacrifices for the greater good.

To mine the seafloor, ships will lower collector vehicles into the depths to vacuum up nodules containing valuable minerals.An old treaty with a new purpose

Countries regulate seabed mining within their marine territories. Farther out, in areas beyond national jurisdiction, they cooperate through the Law of the Sea Convention[11], which has been ratified by 167 countries and the European Union, but not the U.S.

The treaty created the International Seabed Authority[12], headquartered in Jamaica, to manage seabed mining in international waters. This organization’s workload is about to balloon.

Under the treaty, activities conducted in areas beyond national jurisdiction must be for “the benefit of mankind as a whole[13].” These benefits could include economic profit, scientific research findings, specialized technology and recovery of historical objects. The convention calls on governments to share them fairly, with special attention to developing countries’ interests and needs.

The United States was involved in negotiating the convention and signed it but has not ratified it[14], due to concerns that it puts too many limits on exploitation of deep sea resources. As a result, the U.S. is not bound by the treaty, although it follows most of its rules independently. Recent administrations, including those of Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, sought to ratify the treaty, but failed to muster a two-thirds majority[15] in the Senate to support it.

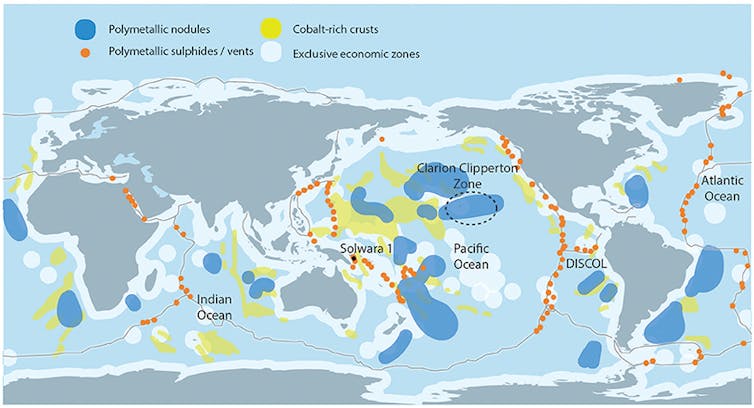

Locations of three main types of marine mineral deposits: polymetallic nodules (blue); polymetallic or seafloor massive sulfides (orange); and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts (yellow). Miller et al., 2018, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00418, CC BY[16][17]

Locations of three main types of marine mineral deposits: polymetallic nodules (blue); polymetallic or seafloor massive sulfides (orange); and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts (yellow). Miller et al., 2018, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00418, CC BY[16][17]

Powering digital devices

Scientists and industry leaders have known that there are valuable minerals on the seafloor for over a century, but it hasn’t been technologically or economically feasible to go after them until the past decade. Widespread growth of battery-driven technologies such as smartphones, computers, wind turbines and solar panels is changing this calculation[18] as the world runs low on land-based deposits of copper, nickel, aluminum, manganese, zinc, lithium and cobalt.

These minerals are found in potato-shaped “nodules” on the seafloor, as well as in and around hydrothermal vents[19], seamounts and midocean ridges. Energy companies and their governments are also interested in extracting methane hydrates[20] – frozen deposits of natural gas on the seafloor.

Scientists still have a lot to learn about these habitats and the species that live there. Research expeditions are continually discovering new species in deep-sea habitats[21].

Korea and China seek the most contracts

Mining the deep ocean requires permission from the International Seabed Authority. Exploration contracts provide the right to explore a specific part of the seabed for 15 years. As of mid-2020, 30 mining groups have signed exploration contracts[22], including governments, public-private partnerships, international consortiums and private multinational companies.

Two entities hold the most exploration contracts (three each): the government of Korea and the China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association[23], a state-owned company. Since the U.S. is not a member of the Law of the Sea treaty, it cannot apply for contracts. But U.S. companies are investing in others’ projects. For example, the American defense company Lockheed Martin owns UK Seabed Resources[24], which holds two exploration contracts.

Once an exploration contract expires, as several have since 2015, mining companies must broker an exploitation contract with the International Seabed Authority to allow for commercial-scale extraction. The agency is working on rules for mining[25], which will shape individual contracts.

Unknown ecological impacts

Deep-sea mining technology is still in development but will probably include vacuuming nodules from the seafloor. Scraping and vacuuming the seafloor can destroy habitats and release plumes of sediment[26] that blanket or choke filter-feeding species on the seafloor and fish swimming in the water column.

Mining also introduces noise, vibration and light pollution[27] in a zone that normally is silent, still and dark. And depending on the type of mining taking place, it could lead to chemical leaks and spills.

Many deep-sea species are unique and found nowhere else[28]. We agree with the scientific community[29] and environmental advocates[30] that it is critically important to analyze the potential effects of seabed mining thoroughly. Studies also should inform decision-makers about how to manage the process.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[31].]

This is a key moment for the International Seabed Authority. It is currently writing the rules for environmental protection but doesn’t have enough information about the deep ocean and the impacts of mining. Today the agency relies on seabed mining companies to report on and monitor themselves, and on academic researchers to provide baseline ecosystem data.

We believe that national governments acting through the International Seabed Authority should require more scientific research and monitoring[32], and better support the agency’s efforts to analyze and act on that information. Such action would make it possible to slow the process down and make better decisions about when, where and how to mine the deep seabed.

Footage from an expedition to the Ningaloo Canyons off Western Australia in spring 2020 that discovered up to 30 new species.Balancing risks and benefits

The race for deep-sea minerals is imminent[33]. There are compelling arguments for mining the seabed, such as supporting the transition to renewable energy[34], which some companies assert will be a net gain for the environment[35]. But balancing benefits and impacts will require proactive and thorough study before the industry takes off.

We also believe that the U.S. should ratify the Law of the Sea treaty so that it can help to lead on this issue. The oceans provide humans with food and oxygen and regulate Earth’s climate[36]. Choices being made now could affect them far into the future in ways that aren’t yet understood.

Dr. Rachel Tiller, Senior Research Scientist with SINTEF Ocean, Norway, contributed to this article.

References

- ^ belongs to everyone (www.un.org)

- ^ within countries’ marine territories (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ As soon as 2025 (www.scientificamerican.com)

- ^ ocean policy (scholar.google.com)

- ^ marine resource management (scholar.google.com)

- ^ international ocean governance (scholar.google.com)

- ^ environmental regimes (scholar.google.com)

- ^ political processes that govern deep seabed mining (doi.org)

- ^ sharing marine resources equitably (doi.org)

- ^ marine protected areas (dx.doi.org)

- ^ Law of the Sea Convention (www.un.org)

- ^ International Seabed Authority (www.isa.org.jm)

- ^ the benefit of mankind as a whole (www.un.org)

- ^ has not ratified it (sites.tufts.edu)

- ^ failed to muster a two-thirds majority (www.voanews.com)

- ^ Miller et al., 2018, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00418 (www.frontiersin.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ changing this calculation (www.carbonbrief.org)

- ^ hydrothermal vents (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

- ^ methane hydrates (e360.yale.edu)

- ^ discovering new species in deep-sea habitats (newatlas.com)

- ^ 30 mining groups have signed exploration contracts (www.isa.org.jm)

- ^ China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association (www.comra.org)

- ^ UK Seabed Resources (www.lockheedmartin.com)

- ^ rules for mining (www.isa.org.jm)

- ^ release plumes of sediment (doi.org)

- ^ noise, vibration and light pollution (doi.org)

- ^ unique and found nowhere else (doi.org)

- ^ scientific community (dx.doi.org)

- ^ environmental advocates (www.deepseaminingoutofourdepth.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ require more scientific research and monitoring (doi.org)

- ^ race for deep-sea minerals is imminent (www.economist.com)

- ^ supporting the transition to renewable energy (www.mining-technology.com)

- ^ net gain for the environment (news.mongabay.com)

- ^ provide humans with food and oxygen and regulate Earth’s climate (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

Authors: Elizabeth M. De Santo, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, Franklin & Marshall College