COVID-19 has resurrected single-use plastics – are they back to stay?

- Written by Jessica Heiges, PhD Candidate in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley

COVID-19 is changing[1] how the U.S. disposes of waste. It is also threatening hard-fought victories that restricted or eliminated single-use disposable items, especially plastic, in cities and towns across the nation.

Our research group[2] is analyzing how the pandemic has altered waste management strategies. Plastic-Free July[3], an annual campaign launched in 2011, is a good time to assess what has happened to single-use disposable plastics under COVID-19, and whether efforts to curb their use can get back on track.

California banned single-use plastic bags in 2016, but state officials waived the ban during COVID-19 quarantines because plastic was perceived as more sanitary.From plans to pandemic

Over several decades leading up to 2020, many U.S. cities and states worked to reduce waste from single-use disposable objects such as straws, utensils, coffee cups, beverage bottles and plastic bags. Policies varied but included bans on Styrofoam[4], plastic bags[5] and straws, along with taxes and fees on bottles[6] and cups[7].

Social norms[8] around plastic waste have evolved quickly in the past several years. Pre-COVID-19, “Bring your own” tote bags, mugs and other foodware had become part of daily life for many consumers. Innovative startups targeting reusable foodware niches include Vessel[9], which partners with cafes, enabling customers to rent stainless steel to-go mugs, and DishCraft[10], which picks up dirty dishes from dine-in restaurants and to-go food outlets, cleans them with high-tech equipment and returns them ready for reuse.

Just before COVID-19 lockdowns began in March 2020, the New Jersey senate adopted a bill[11] that would have made the state the first to ban all single-use bags made of either paper or plastic. And U.S. Sen. Tom Udall of New Mexico and U.S. Rep. Alan Lowenthal of California introduced the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act[12] – the first federal measure limiting use of single-use disposable items.

COVID-19 shutdowns drastically changed[13] all of this. In just a few weeks, plastic bags returned to grocery stores[14] in states that had recently banned them. Even before lockdowns were official, restaurants and cafes started refusing personal reusables[15] such as coffee mugs, reverting to plastic cups and lids, wrapped straws and condiment packets.

By late June, cities and states had temporarily suspended[16] almost 50 single-use item reduction policies across the U.S. – mainly bans plastic bag bans. The pandemic also spurred demand for single-use personal protective equipment, such as masks[17] and plastic gloves. These items soon began appearing in municipal solid waste streams and discarded on streets[18].

The plastic pandemic

With legislation restricting disposables suspended, many food vendors and grocery stores have shifted entirely to disposable bags, plates and cutlery. This switch has raised their operating costs[19] and cut further into their already-low margins.

Grocery stores have sharply increased[20] plastic bag usage. Households are generating up to 50% more waste by volume[21] than they did pre-COVID-19. Anecdotal reports indicate that these waste streams contain more single-use disposable items[22].

The recycling industry has weighed in[23] on the impacts of more single-use bags and higher residential waste volumes. Waste industry workers, who have been uniformly declared essential, work in closed spaces with many other people, so even if surface transmission of coronavirus is not a serious risk, the pandemic has increased person-to-person transmission risks[24] in the waste industry.

Hygiene: A red herring

The main rationale that states, cities and vendors have offered to justify switching from reusables back to disposables is hygiene[25]. Plastic packaging, the argument goes, protects public health by keeping contents safe and sealed[26]. Also, discarding items immediately after use protects consumers from infection.

This narrative handily dovetails with the plastics industry’s ongoing effort[27] to slow or derail bans and restrictions. The industry has loudly supported[28] turning the clock back toward single-use disposable products.

[The Conversation’s newsletter explains what’s going on with the coronavirus pandemic. Subscribe now[29].]

In a March 2020 letter[30] to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Plastics Industry Association argued that single-use items were the “most sanitary” option for consumers. Industry representatives are actively lobbying against[31] the Break Free From Plastics Act.

However, studies show that these products are not necessarily safer[32] than reusable alternatives with respect to COVID-19. The virus survives as long on plastic[33] as it does on other surfaces such as stainless steel. What’s more, studies currently cited by the plastics industry focus on other contaminants[34] such as E.coli and listeria bacteria, not on coronaviruses.

Viewed more holistically, plastics generate pollutants upstream when their raw materials are extracted and plastic goods are manufactured and transported. After disposal – typically via landfills or incineration – they release pollutants that can seriously affect environmental and human health[35], including hazardous and endocrine disrupting chemicals.

All of these impacts are especially harmful to minority and marginalized populations, who are already more vulnerable[36] to COVID-19. In our view, plastic goods are far from being the most hygienic or beneficial to public health, especially over the long term.

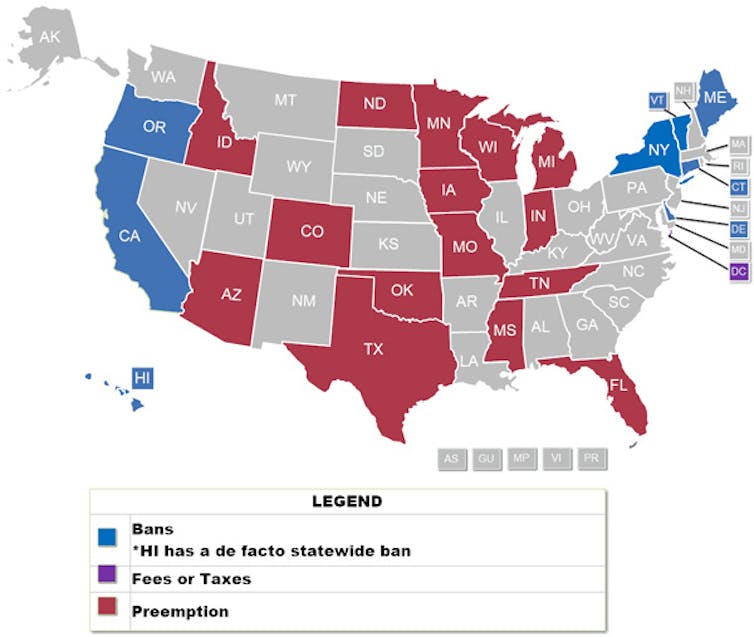

States with enacted plastic bag legislation as of Jan. 24, 2020. Preemption means a state has adopted a law barring state or local regulation of plastic bags – measures often promoted by the affected industry.

NCSL, CC BY-ND[37][38]

States with enacted plastic bag legislation as of Jan. 24, 2020. Preemption means a state has adopted a law barring state or local regulation of plastic bags – measures often promoted by the affected industry.

NCSL, CC BY-ND[37][38]

Building resilience

Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic make it hard to see the bigger picture[39]. No longer having to remember reusable tote bags or coffee mugs can be a relief. But the quick return of single-use disposable products shows that recent restrictions are precarious, and that industries don’t cede profitable markets without a fight.

Waste reduction advocates, such as Upstream Solutions[40] and #BreakFreeFromPlastic[41], are working to gather data, educate the public and prevent decision-making about plastics that is based on perception rather than scientific reasoning. On June 22, 115 health experts worldwide released a statement arguing that reusables are safe even under pandemic conditions[42].

Some governments are taking notice. In late June, California reinstated its statewide ban[43] on single-use plastic bags and requirement for plastic bags to contain 40% recycled materials. Massachusetts quickly followed suit[44], lifting a temporary ban on reusable bags.

For the longer term, it is unclear how COVID-19 disruptions will affect consumerism and waste disposal practices. In our view, one important takeaway is that while mindful consumers are part of the solution to the plastics crisis, individuals cannot and should not carry the full burden.

We believe that at the local[45] and federal[46] levels, policymakers need to build cross-jurisdictional alliances, recognizing shared interests with the waste management industry[47] and emerging businesses like Vessel and Dishcraft. To make progress on reducing plastic waste, advocates need to reinforce measures in place before the next crisis hits.

References

- ^ changing (theconversation.com)

- ^ Our research group (ourenvironment.berkeley.edu)

- ^ Plastic-Free July (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Styrofoam (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ plastic bags (www.ncsl.org)

- ^ bottles (www.bottlebill.org)

- ^ cups (www.cityofberkeley.info)

- ^ Social norms (doi.org)

- ^ Vessel (vesselworks.org)

- ^ DishCraft (dishcraft.com)

- ^ adopted a bill (www.njleg.state.nj.us)

- ^ Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act (www.tomudall.senate.gov)

- ^ drastically changed (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ plastic bags returned to grocery stores (www.waste360.com)

- ^ refusing personal reusables (www.wastedive.com)

- ^ temporarily suspended (docs.google.com)

- ^ masks (d2zly2hmrfvxc0.cloudfront.net)

- ^ discarded on streets (www.cnn.com)

- ^ operating costs (www.sfexaminer.com)

- ^ sharply increased (www.latimes.com)

- ^ 50% more waste by volume (chicago.suntimes.com)

- ^ more single-use disposable items (theconversation.com)

- ^ weighed in (www.wastedive.com)

- ^ increased person-to-person transmission risks (www.sfchronicle.com)

- ^ hygiene (blogs.worldbank.org)

- ^ safe and sealed (theconversation.com)

- ^ ongoing effort (www.wastedive.com)

- ^ loudly supported (www.wastedive.com)

- ^ Subscribe now (theconversation.com)

- ^ letter (www.politico.com)

- ^ actively lobbying against (www.politico.com)

- ^ not necessarily safer (doi.org)

- ^ survives as long on plastic (dx.doi.org)

- ^ other contaminants (doi.org)

- ^ environmental and human health (doi.org)

- ^ more vulnerable (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ NCSL (www.ncsl.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ the bigger picture (hbr.org)

- ^ Upstream Solutions (www.upstreamsolutions.org)

- ^ #BreakFreeFromPlastic (www.breakfreefromplastic.org)

- ^ safe even under pandemic conditions (www.greenpeace.org)

- ^ reinstated its statewide ban (resource-recycling.com)

- ^ quickly followed suit (www.bostonglobe.com)

- ^ local (www.berkeleyside.com)

- ^ federal (www.wastedive.com)

- ^ waste management industry (wastewise.be)

Authors: Jessica Heiges, PhD Candidate in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley