3 things 'ZeroZeroZero' gets right about the cocaine trade

- Written by Kendra McSweeney, Professor of Geography, The Ohio State University

The Amazon Prime Video series “ZeroZeroZero”[1] shows U.S. viewers an accurate picture of the modern cocaine trade that’s rarely seen on screen. It is loosely based on[2] Italian journalist Roberto Saviano’s nonfiction book[3] by the same name.

I study cocaine trafficking and U.S. drug policy, and the show reveals three truths that challenge the U.S. government’s justification for its war against cocaine trafficking in Central America and Mexico.

1. Most cocaine isn’t destined for US markets

A fundamental government assumption is that any cocaine smuggled north out of South America, where it is produced, is inevitably bound for American streets.

That is why the U.S. spends billions of dollars[4] every year attempting to intercept the boats and planes that shuttle cocaine from South America to Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean – an area known to anti-drug forces as the “transit zone[5].”

In 2018, for instance, the U.S. military trumpeted its role in drug seizures in the region by claiming that American forces had “helped keep the equivalent of 600 minivans[6] full of cocaine off U.S. streets.” By the same logic, the federal government considers anyone caught moving cocaine anywhere in the transit zone to be threatening the U.S.

That assumption is behind the March 2020 federal indictment of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro[7] for, among other things, exporting cocaine to Honduras – which prosecutors claimed was “expressly intended to flood the United States with cocaine.”

And it’s behind the recent federal complaint against Honduras’ former chief of police[8], who had allegedly conspired to “transport the drugs westward in Honduras towards the border with Guatemala and eventually the United States.”

Neither case offers proof that the cocaine involved actually entered U.S. territory. U.S. law[9] requires only that the intent be there, and it is assumed that traffickers must intend for the cocaine to reach the U.S. After all, where else would it go?

“ZeroZeroZero” offers the inconvenient answer. Episode 1 takes viewers to northern Mexico as 5.5 tons (5,000 kilograms) of cocaine in sealed pucks are being hidden in the bottom of cans of chilis. Even though the cocaine has made it as far north as Monterrey – less than three hours’ drive from Laredo, Texas – viewers learn by Episode 2 that the drugs are not going to the Mexico-U.S. border. Instead, they take a sharp turn southeast and are loaded onto a container ship at the port of Tampico, headed for Italy.

This is why the show shines. It depicts a little-known reality: Far more cocaine is transshipped through Central America and Mexico to markets worldwide than finds its way up American nostrils.

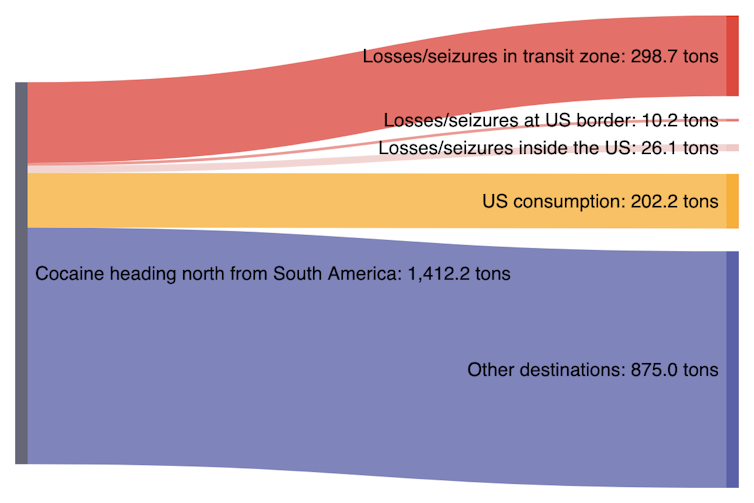

From 2012 through 2016, federal data show that, on average, most of the cocaine leaving South America and heading north each year was destined for somewhere other than the U.S.

The Conversation via SankeyMATIC, with data from Kendra McSweeney, CC BY-ND[10]

From 2012 through 2016, federal data show that, on average, most of the cocaine leaving South America and heading north each year was destined for somewhere other than the U.S.

The Conversation via SankeyMATIC, with data from Kendra McSweeney, CC BY-ND[10]

How do I know? Illicit commodities are notoriously hard to track. But as I explain in a recent article[11], an obscure U.S. government data set has for years been compiling reliable intelligence on cocaine traffic through the transit zone. When compared alongside analysts’ best estimates[12] of cocaine consumption in the U.S., the data tell an intriguing story.

Between 2012 and 2016 – years for which there are comparable data – an average of at least 1,400 tons[13] of high-purity cocaine was annually exported north out of South America and into the transit zone. Of that, law enforcement removed about 335 tons[14] yearly, whether in the transit zone, at the border or within the the U.S[15]. In the same period, U.S. cocaine users consumed on average barely 200 tons[16] per year. That means they used less than one-fifth of the available cocaine flow.

So where did the majority of the remaining cocaine go – almost 900 tons a year? There are no comparable sources for the amount consumed in transit zone countries or in Canada. There is, however, strong evidence to suggest that hundreds of tons annually are being trafficked through Mexico and Central America and out to Europe, and across the Pacific to Asia and Australia. Traffickers target those overseas markets for good reason: That’s where the money is, and they have a cheap way to get cocaine there.

The cinematography is stunning, and so is the series’ accuracy.2. The big money is in growing overseas markets

The U.S. government’s assumption wasn’t always wrong. A generation ago, the Western Hemisphere cocaine trade did function like a pipeline that started in South America, wound through Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean, and discharged cocaine almost exclusively into American neighborhoods.

In 1990, the U.S. had an estimated 4.3 million cocaine users. Meanwhile, Western Europe’s cocaine markets were still in what a United Nations report called “a developmental stage[17].”

Now, the picture is dramatically different. U.S. cocaine consumption has been in a prolonged “nosedive[18],” according to a report from the London School of Economics. In 2018, there were fewer than 2.5 million users[19], with lower rates of adult use than in many European countries. Experts continue to debate[20] why U.S. demand has plummeted. Even the recent and unprecedented surge in cocaine production in Colombia[21], which has increased purity and dropped prices in the U.S., has only just curtailed that long slide.

Meanwhile, cocaine consumption in cities across 20 European countries rose 70% from 2015 to 2019[22]. Demand in Australia is high and growing[23], as it is in Eastern Europe and Russia. Again, “ZeroZeroZero” gets it right: The series ends with the players negotiating a shipment from Mexico to Russia.

Overseas cocaine markets aren’t just expanding. They’re also potentially far more lucrative[24] than North American ones. In 2017, a kilo of cocaine that sold wholesale for US$28,000 in the U.S. went for twice that[25] in Northern Europe. Traffickers stand to make immense profits if they can move large volumes cheaply over long distances.

This is where the containers come in.

‘ZeroZeroZero’ shows container shipping is a key tactic for moving drugs.

Amazon[26]

‘ZeroZeroZero’ shows container shipping is a key tactic for moving drugs.

Amazon[26]

3. Bulk cocaine is exported from Mexico and Central America in shipping containers

Mexico and Central America boast three of Latin America’s five busiest maritime ports[27]. The busiest of all is Colón, the Caribbean terminus of the Panama Canal, which after the canal’s recent expansion can handle 4.3 million shipping containers[28] per year. In fact, maritime port facilities across the region have been upgraded in recent years, with new capacities and efficiencies that have lowered costs and enhanced the region’s competitiveness as a transoceanic trade hub.

Cocaine traffickers are taking full advantage. The port of Colón has become a major hub for Europe-bound cocaine[29]. Similarly, Costa Rica’s recently enhanced Limón-Moín port facilities[30] have been a boon[31] for trans-Atlantic cocaine shipping. In February 2020, inspectors there found 5 tons of cocaine[32] in a shipment of ornamental plants destined for the Netherlands.

The same month, a container of mashed bananas out of Limón was stopped in Italy with 3.3 tons of cocaine inside[33]. In May 2020, a container full of coffee left Honduras’ newly expanded port of Cortés[34]. Upon arrival at Le Havre, France, 1.5 tons of cocaine[35] were found among the coffee beans.

These are just some of the cocaine seizures that made headlines in the last several months. At best, 1 in 10[36] containers circumnavigating the globe is searched by authorities; the rate is even lower for containers holding perishable commodities like plants and fruit[37]. So these seizures, while large, likely represent just a fraction of the cocaine transshipped via container out of Central America and Mexico.

As “ZeroZeroZero” shows, cocaine traffickers operating in Mexico and Central America may be working in the United States’ proverbial back yard, but their distribution networks reach much more widely than they used to. The U.S. is no longer cocaine’s true north.

References

- ^ “ZeroZeroZero” (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ based on (www.refinery29.com)

- ^ Roberto Saviano’s nonfiction book (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ billions of dollars (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ transit zone (www.gao.gov)

- ^ helped keep the equivalent of 600 minivans (www.southcom.mil)

- ^ Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro (www.justice.gov)

- ^ Honduras’ former chief of police (www.justice.gov)

- ^ U.S. law (www.govinfo.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ recent article (doi.org)

- ^ analysts’ best estimates (www.rand.org)

- ^ 1,400 tons (www.oig.dhs.gov)

- ^ 335 tons (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ within the the U.S (www.dea.gov)

- ^ 200 tons (www.rand.org)

- ^ a developmental stage (www.unodc.org)

- ^ nosedive (www.lse.ac.uk)

- ^ fewer than 2.5 million users (wdr.unodc.org)

- ^ continue to debate (www.lse.ac.uk)

- ^ surge in cocaine production in Colombia (wdr.unodc.org)

- ^ 20 European countries rose 70% from 2015 to 2019 (wdr.unodc.org)

- ^ high and growing (theconversation.com)

- ^ far more lucrative (www.dea.gov)

- ^ twice that (dataunodc.un.org)

- ^ Amazon (www.imdb.com)

- ^ five busiest maritime ports (www.cepal.org)

- ^ 4.3 million shipping containers (www.statista.com)

- ^ hub for Europe-bound cocaine (www.maritime-executive.com)

- ^ enhanced Limón-Moín port facilities (www.thecentralamericangroup.com)

- ^ boon (www.insightcrime.org)

- ^ 5 tons of cocaine (www.insightcrime.org)

- ^ 3.3 tons of cocaine inside (www.freshplaza.com)

- ^ newly expanded port of Cortés (www.seatrade-maritime.com)

- ^ 1.5 tons of cocaine (criterio.hn)

- ^ 1 in 10 (www.wsj.com)

- ^ fruit (www.insightcrime.org)

Authors: Kendra McSweeney, Professor of Geography, The Ohio State University

Read more https://theconversation.com/3-things-zerozerozero-gets-right-about-the-cocaine-trade-135289