What is a derecho? An atmospheric scientist explains these rare but dangerous storm systems

- Written by Russ Schumacher, Associate Professor of Atmospheric Science and Colorado State Climatologist, Colorado State University

Thunderstorms are common across North America, especially in warm weather months. About 10% of them become severe[1], meaning they produce hail 1 inch or greater in diameter, winds gusting in excess of 50 knots (57.5 miles per hour), or a tornado.

The U.S. recently has experienced two rarer events: organized lines of thunderstorms with widespread damaging winds, known as derechos.

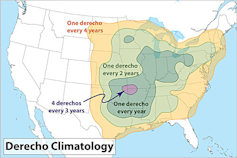

Derechos occur fairly regularly over large parts of the U.S. each year, most commonly from April through August.

Dennis Cain/NOAA[2]

Derechos occur fairly regularly over large parts of the U.S. each year, most commonly from April through August.

Dennis Cain/NOAA[2]

Derechos occur mainly across the central and eastern U.S., where many locations are affected one to two times per year on average. They can produce significant damage to structures and sometimes cause “blowdowns” of millions of trees. Pennsylvania and New Jersey received the brunt[3] of a derecho on June 3, 2020, that killed four people and left nearly a million without power across the mid-Atlantic region.

In the West, derechos are less common, but Colorado – where I serve as state climatologist and director of the Colorado Climate Center[4] – experienced a rare and powerful derecho[5] on June 6 that generated winds exceeding 100 miles per hour in some locations. Derechos have also been observed and analyzed in many other parts of the world, including Europe, Asia and South America.

Derechos are an important and active research area in meteorology. I expect that at least one or two more will occur somewhere in the U.S. this summer. Here’s what we know about these unusual storms.

A massive derecho in June 2012 developed in northern Illinois and traveled to the mid-Atlantic coast, killing 22 and causing $4 billion to $5 billion in damages.Walls of wind

Scientists have long recognized that organized lines of thunderstorms can produce widespread damaging winds. Gustav Hinrichs[6], a professor at the University of Iowa, analyzed severe winds in the 1870s and 1880s and identified that many destructive storms were produced by straight-line winds rather than by tornadoes, in which winds rotate. Because the word “tornado,” of Spanish origin, was already in common usage, Hinrichs proposed “derecho” – Spanish for “straight ahead” – for damaging windstorms not associated with tornadoes.

In 1987, meteorologists defined what qualified as a derecho[7]. They proposed that for a storm system to be classified as a derecho, it had to produce severe winds – 57.5 mph (26 meters per second) or greater – and those intense winds had to extend over a path at least 250 miles (400 kilometers) long, with no more than three hours separating individual severe wind reports.

Derechos are almost always caused by a type of weather system known as a bow echo[8], which has the shape of an archer’s bow on radar images. These in turn are a specific type of mesoscale convective system[9], a term that describes large, organized groupings of storms[10].

Researchers are studying whether and how climate change is affecting weather hazards from thunderstorms. Although some aspects of mesoscale convective systems, such as the amount of rainfall they produce, are very likely to change with continued warming, it’s not yet clear how future climate change may affect the likelihood or intensity of derechos.

Speeding across the landscape

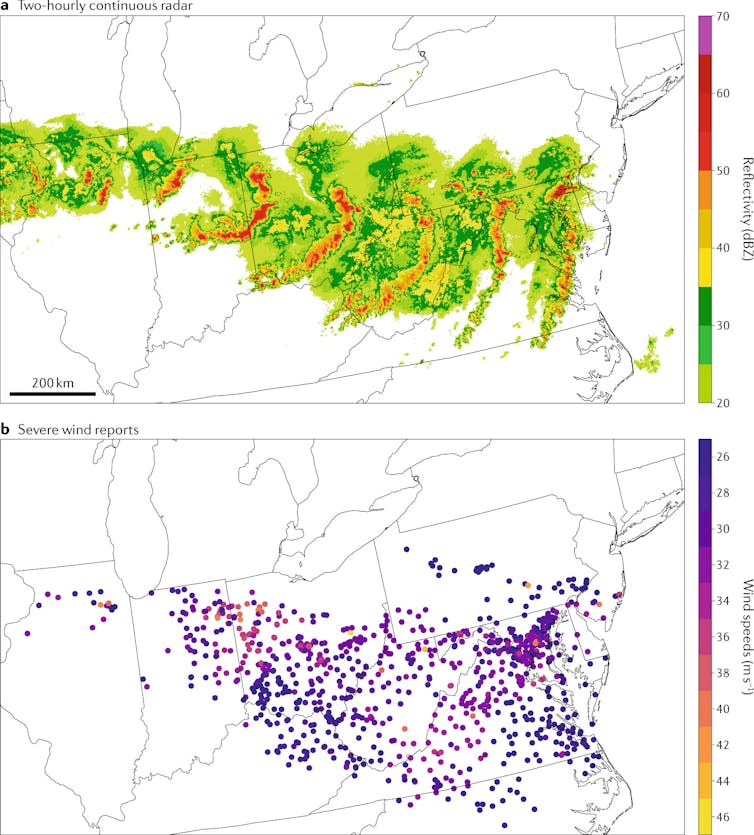

The term “derecho” vaulted into public awareness in June 2012, when one of the most destructive derechos in U.S. history formed in the Midwest and traveled some 700 miles in 12 hours[11], eventually making a direct impact on the Washington, D.C. area. This event killed 22 people and caused millions of power outages.

Top: Radar imagery every two hours, from 1600 UTC 29 June to 0400 UTC 30 June 2012, combined to show the progression of a derecho-producing bow echo across the central and eastern US. Bottom: Severe wind reports for the 29-30 June 2012 derecho, colored by wind speed.

Schumacher and Rasmussen, 2020, adapted from Guastini and Bosart 2016, CC BY-ND[12][13]

Top: Radar imagery every two hours, from 1600 UTC 29 June to 0400 UTC 30 June 2012, combined to show the progression of a derecho-producing bow echo across the central and eastern US. Bottom: Severe wind reports for the 29-30 June 2012 derecho, colored by wind speed.

Schumacher and Rasmussen, 2020, adapted from Guastini and Bosart 2016, CC BY-ND[12][13]

Only a few recorded derechos had occurred in the western U.S. prior to June 6, 2020. On that day, a line of strong thunderstorms developed in eastern Utah and western Colorado in the late morning. This was unusual in itself, as storms in this region tend to be less organized and occur later in the day.

The thunderstorms continued to organize and moved northeastward across the Rocky Mountains. This was even more unusual: Derecho-producing lines of storms are driven by a pool of cold air near the ground, which would typically be disrupted by a mountain range as tall as the Rockies. In this case, the line remained organized.

As the line of storms emerged to the east of the mountains, it caused widespread wind damage in the Denver metro area and northeastern Colorado. It then strengthened further as it proceeded north-northeastward across eastern Wyoming, western Nebraska and the Dakotas.

In total there were nearly 350 reports of severe winds, including 44 of 75 miles per hour (about 34 meters per second) or greater. The strongest reported gust was 110 mph at Winter Park ski area in the Colorado Rockies. Of these reports, 95 came from Colorado – by far the most severe wind reports ever from a single thunderstorm system.

Animation showing the development and evolution of the 6-7 June 2020 western derecho. Radar reflectivity is shown in the color shading, with National Weather Service warnings shown in the colored outlines (yellow polygons indicate severe thunderstorm warnings). Source: Iowa Environmental Mesonet.

Animation showing the development and evolution of the 6-7 June 2020 western derecho. Radar reflectivity is shown in the color shading, with National Weather Service warnings shown in the colored outlines (yellow polygons indicate severe thunderstorm warnings). Source: Iowa Environmental Mesonet.Coloradans are accustomed to big weather, including strong winds in the mountains and foothills. Some of these winds are generated by flow down mountain slopes[14], localized thunderstorm microbursts[15], or even “bomb cyclones[16].” Western thunderstorms more commonly produce hailstorms and tornadoes, so it was very unusual to have a broad swath of the state experience damaging straight-line winds that extended from west of the Rockies all the way to the Dakotas.

Damage comparable to a hurricane

Derechos are challenging to predict. On days when derechos form, it is often uncertain whether any storms will form at all. But if they do, the chance exists for explosive development of intense winds. Forecasters did not anticipate the historic June 2012 derecho until it was already underway.

For the western derecho on June 6, 2020, outlooks showed an enhanced potential for severe storms in Nebraska and the Dakotas two to three days in advance. However, the outlooks didn’t highlight the potential for destructive winds farther south in Colorado until the morning that the derecho formed.

Once a line of storms has begun to develop, however, the National Weather Service routinely issues highly accurate severe thunderstorm warnings 30 to 60 minutes ahead of the arrival of intense winds, alerting the public to take precautions.

Communities, first responders and utilities may have only a few hours to prepare for an oncoming derecho, so it is important to know how to receive severe thunderstorm warnings[17], such as TV, radio and smartphone alerts, and to take these warnings seriously. Tornadoes and tornado warnings often get the most attention, but lines of severe thunderstorms can also pack a major punch.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[18].]

References

- ^ become severe (www.nssl.noaa.gov)

- ^ Dennis Cain/NOAA (www.spc.noaa.gov)

- ^ received the brunt (www.inquirer.com)

- ^ director of the Colorado Climate Center (scholar.google.com)

- ^ rare and powerful derecho (www.coloradoan.com)

- ^ Gustav Hinrichs (www.spc.noaa.gov)

- ^ qualified as a derecho (doi.org)

- ^ bow echo (www.weather.gov)

- ^ mesoscale convective system (doi.org)

- ^ large, organized groupings of storms (doi.org)

- ^ traveled some 700 miles in 12 hours (www.spc.noaa.gov)

- ^ Schumacher and Rasmussen, 2020, adapted from Guastini and Bosart 2016 (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ down mountain slopes (glossary.ametsoc.org)

- ^ microbursts (www.weather.gov)

- ^ bomb cyclones (theconversation.com)

- ^ how to receive severe thunderstorm warnings (www.weather.gov)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Russ Schumacher, Associate Professor of Atmospheric Science and Colorado State Climatologist, Colorado State University