Obamacare's insurance safety net protects many of the millions losing their employer-provided health insurance – but not all

- Written by Simon F. Haeder, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Pennsylvania State University

The loss of 31 million jobs due to coronvirus has an added downside: 27 million[1] have lost job-based health insurance. The worst may still lie ahead. One study estimated that 25 to 43 million people[2] could lose coverage from their employer.

The situation for many Americans feels dramatic. Fortunately, the limited U.S. safety net will be able to cushion some of the fallout for almost 80%[3] through programs like Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program and the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. And, of course, all preexisting conditions are still required to be covered by all insurers.

Yet millions will be left without coverage. As a professor of public policy[4], I believe there are four things you need to consider if you’ve been laid off, or if you didn’t have health insurance before the pandemic.

In Plantation, Florida, an aerial view of a deserted Westfield Broward Mall, taken by a drone on May 5.

Getty Images / Joe Raedle[5]

In Plantation, Florida, an aerial view of a deserted Westfield Broward Mall, taken by a drone on May 5.

Getty Images / Joe Raedle[5]

What do I do if I’ve been laid off and lost coverage?

The good news: For many who have lost their employer-provided coverage, a number of alternatives may exist.

For some, they might now be able to join their spouse’s insurance. Others may be able to maintain their previous coverage through COBRA[6], albeit without the financial subsidy from their employer. This option can get expensive very quickly. Currently, average premiums in the U.S. for individuals amount to US$7,188[7]. The number increases to $20,576 for a family of four[8]. And COBRA adds an additional 2% of premiums for administration.

Due to the loss of income, people in states that expanded Medicaid under care of the ACA could become eligible for Medicaid coverage[9]. In those states, individuals and their families qualify if their income falls below 138% of the federal poverty line. For a family of four, this currently amounts to roughly $36,000[10]. In states that did not expand Medicaid, eligibility rules vary widely[11] but are often quite restrictive.

In Los Angeles, California, the Million Dollar Theater, closed due to the pandemic, offers some comforting words on its marquee.

Getty Images / Frederic J. Brown[12]

In Los Angeles, California, the Million Dollar Theater, closed due to the pandemic, offers some comforting words on its marquee.

Getty Images / Frederic J. Brown[12]

Individuals who do not qualify for their state Medicaid program may find an alternative in coverage purchased on the ACA insurance marketplaces[13]. Here individuals between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty line are eligible for premium support. Those on the low end of the guidelines are also eligible for out-of-pocket support.

Unfortunately, the decision of many states not to expand their Medicaid programs[14] may leave millions of Americans ineligible for public coverage. They fall into the so-called coverage gap[15]. They make less than the 100% of federal poverty line that makes them eligible for ACA marketplace subsidy. Yet they also make too much to qualify for the restrictive state Medicaid program. This situation applies to nonparent adults in 10 states[16], including Texas, Oklahoma and Mississippi.

Importantly, coverage may be available for the children of those who have lost their previous insurance through the Children’s Health Insurance Program[17]. Eligibility limits[18], even in nonexpansion states, are significantly higher.

Finally, individuals can purchase short-term limited duration insurance[19]. While premiums for this type of coverage are significantly cheaper than for ACA-compliant products, their coverage comes with significant gaps. That is, most preventive services, treatment for conditions like cancer or even prescription drugs likely will not be covered. They also require medical underwriting.

What if I didn’t have insurance in the first place?

A global pandemic seems like a particularly bad time to go without coverage. Yet we know that millions of Americans are eligible for public coverage but remain unenrolled[20]. For many of them, many of the same options described above may apply, including Medicaid, CHIP, spousal coverage and short-term limited duration health plans.

The situation is more complex for those seeking to purchase insurance on their own. The ACA insurance marketplaces[21] generally require that individuals purchase coverage during their open enrollment period. This occurs generally in November and December. The requirement is intended to keep insurance markets stable and not simply allow individuals to obtain coverage only when they fall sick.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, at least nine states[22] have made an exception and reopened their marketplaces temporarily. These include Colorado and Connecticut.

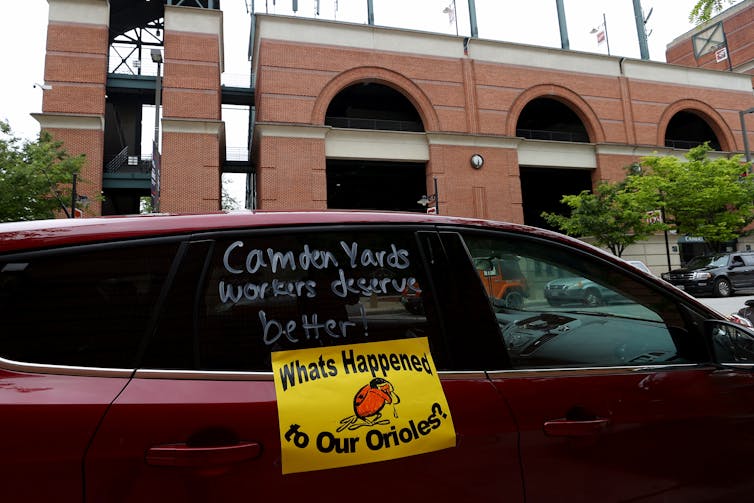

Outside Camden Yards in Baltimore, Maryland, concession workers call for the Baltimore Orioles baseball team to pay the workers unemployment insurance benefits. The start of the baseball season has been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Getty Images / Rob Carr[23]

Outside Camden Yards in Baltimore, Maryland, concession workers call for the Baltimore Orioles baseball team to pay the workers unemployment insurance benefits. The start of the baseball season has been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Getty Images / Rob Carr[23]

What if I fall sick and don’t have insurance?

If you fall sick and need medical help but are currently uninsured, you should not hesitate to seek care.

Many providers, particularly hospitals and federally qualified health centers, will actively seek to enroll you into public coverage like Medicaid. Importantly, Medicaid coverage in most states can be applied retroactively for three months. However, a few states like Arizona and Iowa[24] have obtained permission to exclude this benefit.

Even then, many states have longstanding protections for uninsured individuals that requires providers to use so-called sliding scales, the adjustment of fees based on income. Others have local programs[25] that may help pay for your care. The CARES Act[26] also provides reimbursement for some COVID-19-related care[27] directly to providers.

Importantly, if you get a bill, try to negotiate with the provider. Legal aid societies[28] across the country are there to help in this process.

How the ACA lawsuit may impact health insurance coverage

From a policy perspective, the coronavirus pandemic starkly highlights the need for a strong safety net. It is also offers a reminder of the benefits that the ACA[29] provides to millions of Americans on a daily basis. Without it, millions more would lose their coverage.

It is important to remember that the ACA’s constitutionality is currently in litigation once more before the Supreme Court[30]. The Trump administration has taken a virtually unprecedented step and refused to defend it. It has also argued that if any of the law is struck down, it should fall in its entirety. Of course, should this occur, the implications for the U.S.[31] could be dramatic. On the other hand, should former Vice President Joe Biden come to office with a large Democratic majority in both chambers, it seems realistic to expect him to move forward with expanding the ACA and seeking the inclusion of the so-called public option[32].

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter[33].]

References

- ^ 27 million (www.kff.org)

- ^ 25 to 43 million people (www.rwjf.org)

- ^ 80% (www.kff.org)

- ^ professor of public policy (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Getty Images / Joe Raedle (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ through COBRA (www.dol.gov)

- ^ US$7,188 (www.kff.org)

- ^ $20,576 for a family of four (www.kff.org)

- ^ Medicaid coverage (theconversation.com)

- ^ roughly $36,000 (aspe.hhs.gov)

- ^ vary widely (www.medicaid.gov)

- ^ Getty Images / Frederic J. Brown (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ ACA insurance marketplaces (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ not to expand their Medicaid programs (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ coverage gap (www.kff.org)

- ^ 10 states (www.kff.org)

- ^ Children’s Health Insurance Program (theconversation.com)

- ^ Eligibility limits (www.macpac.gov)

- ^ short-term limited duration insurance (theconversation.com)

- ^ but remain unenrolled (www.milkenreview.org)

- ^ ACA insurance marketplaces (www.degruyter.com)

- ^ at least nine states (www.npr.org)

- ^ Getty Images / Rob Carr (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ a few states like Arizona and Iowa (www.kff.org)

- ^ local programs (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ CARES Act (www.congress.gov)

- ^ reimbursement for some COVID-19-related care (www.hhs.gov)

- ^ Legal aid societies (www.lsc.gov)

- ^ benefits that the ACA (theconversation.com)

- ^ once more before the Supreme Court (theconversation.com)

- ^ implications for the U.S. (theconversation.com)

- ^ so-called public option (www.milkenreview.org)

- ^ You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Simon F. Haeder, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Pennsylvania State University