Hoarding during the coronavirus isn't just unnecessary, it's ethically wrong

- Written by Jaime Ahlberg, Associate Professor of Philosophy, University of Florida

As people rush to stockpile provisions[1] in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, stores have placed restrictions on the purchase of basic goods[2] and medicines[3].

When supply chains are vulnerable to spikes in demand, one person’s stockpiling can mean another person’s shortage.

As a philosopher who has studied[4] ethical action in difficult circumstances, I know that when many people fail to act ethically, it can seem that each individual has less of an obligation to act well.

At this time, American political philosopher John Rawls’ theory of justice can offer useful moral guidance.

Ethics for difficult times

John Rawls famously argued[5] that in a fully just society, two circumstances are in place: everyone upholds the just society, and conditions of life are reasonably favorable.

When society is not fully just, people don’t necessarily have to follow the rules. Rawls argued that if there was systemic injustice, civil disobedience can be justified[6]. For example, when a minority group is denied the vote, protesters are permitted to disrupt business and stage sit-ins.

Other scholars, following this kind of argument, have said that it can be ethical to lie[7], when doing so thwarts others’ evil plans.

In other words, individuals are allowed to deviate from the cooperative norms that underpin a fully just society, under certain circumstances. Nevertheless, scholars also argue that there are some lines one must not cross, even when others act badly and conditions are difficult.

For Rawls[8], a particularly significant set of requirements include the “natural duties.”

These apply to all people and hold in virtually all circumstances. They include refraining from causing unnecessary suffering and harm to innocents, and not aggravating injustice, when possible.

Stockpiling can cause harm

The warning against harming innocent others or increasing the risk of harm, is relevant to most forms of stockpiling.

Consumers stocking up on medical grade face masks contribute to shortages[9] of supplies for health care workers, which is not ethically permissible.

Similarly, buying up hand sanitizer[10] to sell at premium rates depletes the supply of what has come to be an essential good, not out of need but out of greed. It, too, unnecessarily puts others in harm’s way.

There are less obvious ways in which our shopping behavior can perpetrate harms, or risk of harms, on innocent third parties.

Consider the effects on grocery store workers[11]. Frequent trips to the store may pose a risk to low-wage workers who have virtually no pandemic preparedness training. It increases their vulnerability to infection.

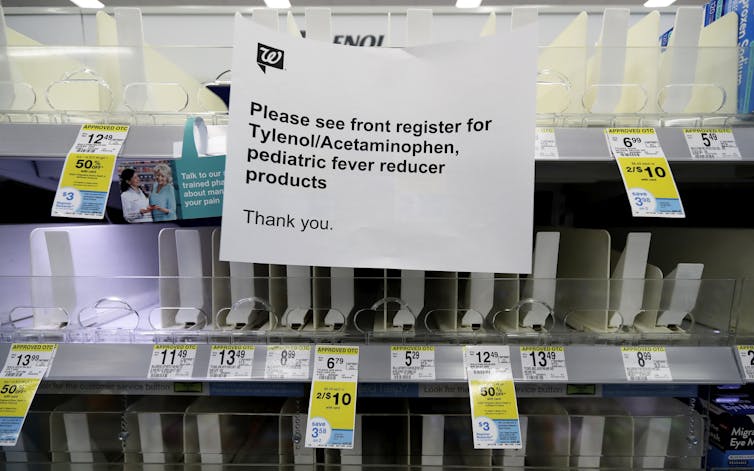

Stockpiling can leave some families without medicines.

AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh[12]

Stockpiling can leave some families without medicines.

AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh[12]

Venturing to the grocery store to buy only what is needed, and less often, is a more ethical solution.

Stockpiling can aggravate injustice

Amassing goods during short-term shortages can increase the economic disadvantages[13] that many people already suffer.

Consider those who cannot afford to stockpile. Hoarding makes it more difficult for those who are less privileged to get what they need when they do shop.

Stockpiling can also turn people against each other. Other shoppers could transform from fellow members of our community, into obstacles to survival and well-being.

This view of others undermines the very possibility[14] of social cooperation, which is a precondition of a just society.

Some exceptions

Still, one is permitted to protect one’s life[15].

Some people have a genuine need for drugs to manage asthma, for example[16]. Securing the drug supply that one will predictably need is warranted. If limited supply means that not all asthma sufferers can get drugs, then no just resolution[17] is possible.

But importantly, this concern will not apply to most people, for most goods. No evidence[18] supports the view that food supply chains are dangerously vulnerable right now, for instance.

Stockpiling can perpetrate harm and threaten the social cohesion that is foundational to a well-ordered society. Even when others stockpile, one has the obligations to do no harm and to do what one can to support social cooperation.

These priorities are important to keep in mind as new and difficult ethical problems emerge during this pandemic.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter[19].]

References

- ^ stockpile provisions (www.independent.co.uk)

- ^ basic goods (www.cnn.com)

- ^ medicines (www.providencejournal.com)

- ^ studied (www.taylorfrancis.com)

- ^ John Rawls famously argued (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ civil disobedience can be justified (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ it can be ethical to lie (www.jstor.org)

- ^ For Rawls (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ contribute to shortages (www.vox.com)

- ^ buying up hand sanitizer (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ grocery store workers (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh (www.apimages.com)

- ^ economic disadvantages (bostonreview.net)

- ^ undermines the very possibility (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ one is permitted to protect one’s life (www.jstor.org)

- ^ for example (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ no just resolution (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ No evidence (slate.com)

- ^ Read The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Jaime Ahlberg, Associate Professor of Philosophy, University of Florida