10 ways to spot online misinformation

- Written by H. Colleen Sinclair, Associate Professor of Social Psychology, Mississippi State University

Propagandists are already working to sow disinformation and social discord[1] in the run-up to the November elections.

Many of their efforts have focused on social media, where people’s limited attention spans push them to share items before even reading them[2] – in part because people react emotionally, not logically[3], to information they come across. That’s especially true when the topic confirms what a person already believes[4].

It’s tempting to blame bots and trolls for these problems. But really it’s our own fault[5] for sharing so widely. Research has confirmed that lies spread faster than truth[6] – mainly because lies are not bound to the same rules as truth.

As a psychological scientist who studies propaganda, here is what I tell my friends, students and colleagues about what to watch out for. That way, they can protect themselves – and each other – from lies, half-truths and misleading spins on current events.

Does this make you angry?1. Did a post spark anger, disgust or fear?

If something you see online causes intense feelings – especially if that emotion is outrage – that should be a red flag not to share it, at least not right away. Chances are it was intended to short-circuit your critical thinking[7] by playing on your emotions. Don’t fall for it.

Instead, take a breath.

The story will still be there after you verify it[8]. If it turns out to be real, and you still want to share it, you may also want to consider the fire you may be contributing to. Do you need to fan the flames?

During these unprecedented times we have to be careful about not contributing to emotional contagions[9]. Ultimately, you are not in charge of alerting the public to breaking news, and you’re not in any race to share things before other people do.

2. Did it make you feel good?

A new tactic being adopted by misinformation warriors is to post feel-good stories[10] that people will want to share. Those pieces may be true or may have as much truth as urban legends. But if lots of people share those posts, it lends legitimacy and credibility to the fake source accounts that originally post the items. Then those accounts are well positioned to share more malicious messages when they judge the time is right.

These same agents use other feel-good ploys as well, including attempts to play on your vanity or inflated self-image[11]. You’ve probably seen posts saying “Only 1% of people are brave enough to share this” or “take this test to see if you are a genius.” Those aren’t benign clickbait – they’re often helping a fraudulent source get shares, build an audience, or in the case of those “personality quizzes” or “intelligence tests” they are trying to get access to your social media profile.

If you encounter a piece like this, if you can’t avoid clicking then just enjoy the good feeling it gives you and move on. Share your own stories rather than those of others.

3. Is it hard to believe?

Carl Sagan.

NASA/JPL[12]

Carl Sagan.

NASA/JPL[12]

What you read may make some extraordinary claim – like the pope endorsing a U.S. presidential candidate[13] when he has never endorsed a candidate before. Astronomer and author Carl Sagan advocated for the response you should have to such claims: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence[14],” which is a longstanding philosophical premise[15]. Consider whether the claim you’re seeing was supported by any evidence at all – and then check that the quality of that evidence out.

Also, remember that a quirk of human psychology means that people only need to hear something three times[16] before the brain starts[17] to think it’s true[18] – even if it’s false.

4. Did it confirm what you already thought?

If you’re reading something that matches so well with what you had already thought, you might be inclined to say “Yep, that’s true” and share it widely.

Meanwhile, differing perspectives get ignored[19].

We are strongly motivated to confirm what we already believe[20] and avoid unpleasant feelings associated with challenges to our beliefs – especially strongly held beliefs.

It is important to identify and acknowledge your biases[21], and take care to be extra critical of articles you agree with. Try seeking to prove them false rather than looking for confirmation they’re true. Be on the lookout because the algorithms are still set up to show you things they think you will like. Don’t be easy prey. Check out other perspectives[22].

5. Am it heard too reed?

Posts that are riddled with spelling and grammatical errors are prime suspects for inaccuracies. If the person who wrote it couldn’t be bothered to spell-check it, they likely didn’t fact-check it either. In fact, they may be using those errors to get your attention[23].

Similarly, a post using multiple fonts could unintentionally reveal that it had material added to the original – or be trying to deliberately catch your eye. (Yes, the errors in the heading for this tip were intentional.)

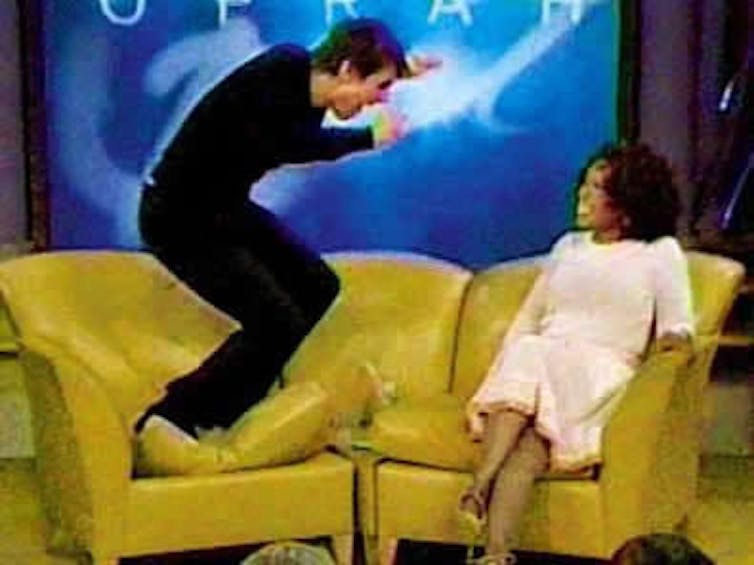

In 2005, Tom Cruise jumped on Oprah’s couch. The moment became a cultural touchstone – and the image became a meme.

Know Your Meme[24]

In 2005, Tom Cruise jumped on Oprah’s couch. The moment became a cultural touchstone – and the image became a meme.

Know Your Meme[24]

6. Was the post a meme?

Memes[25] are usually one or more images or short videos, often with text overlaid, that quickly convey a single idea.

While we may all enjoy a good laugh with a new “Ermahgerd[26]” meme, memes – particularly those sowing political discord – have actually been identified as one of the emerging mediums for propaganda[27]. In recent years, the practice of using memes to incite divisiveness has rapidly escalated[28], and extremist groups[29] are using them with increasing effectiveness.

For example, white supremacist groups have commandeered the “Pepe the frog” meme[30], a cartoonish image that may attract younger audiences[31].

Their origins as benign, humorous images about grumpy cats, cats who want cheeseburgers or calls to “keep calm and carry on” have led our brains to classify memes as enjoyable or, at worse, harmless. Our guards are down. Plus their short nature further subverts critical thinking. Stay alert.

7. What’s the source?

Was the post from an unreliable media outlet? The Media Bias/Fact Check website[32] is one place to look to find out whether a particular news source has a partisan bias. You can also assess the source yourself[33]. Use research-based criteria to judge the quality and balance of the evidence presented. For instance, if an article expresses an opinion, it may present facts slanted in a way favorable to that opinion, rather than fairly presenting all the evidence[34] and drawing a conclusion.

If you find that you’re looking at a suspect site, but the specific article seems accurate, my strong suggestion is to find another credible source for the same information, and share that link instead. When you share something, social media and search-engine algorithms count your sharing as a vote[35] for the overall site’s credibility. So don’t help misinformation sites take advantage of your reputation as a cautious and careful sharer of reliable information.

8. Who said it?

It may be surprising, but politicians and other public figures don’t always tell the truth. It may be accurate that a particular person said a particular sentence, but that doesn’t mean the sentence is correct. You can double-check the alleged fact, of course, but you can also see how truthful particular people are[36].

If you’re hearing information from a friend, of course, there’s no website. You’ll have to rely on old-fashioned critical thinking[37] to evaluate what she says. Is she credible? Does she even have sources? If so, how reliable are those sources? If evaluating the message is too much work, maybe just stick with the “like” button and skip the “share.”

Learn about the Media Bias Chart.9. Is there a hidden agenda?

If you find something that seems compelling and true, check out what nonpartisan sources say on the subject. For a view of media outlets’ perspectives, take a look at the Media Bias Chart[38].

Finding no mention of the topic in nonpartisan media may suggest the statement or anecdote is just a talking point for one side or the other. At minimum, ask yourself why the source chose to write or share that piece. Was it an effort to report and explain things as they were happening, or an attempt to influence your thinking or actions – or your vote?

10. Have you checked the facts?

There are a lot of reputable fact-checking organizations, like Snopes[39] and FactCheck[40]. There is even a dedicated meme-checking site[41]. It doesn’t take long to click over to one of those sites and take a look.

But it can take a very long time to undo the harm of sharing misinformation[42], which can reduce people’s ability to trust evidence and their fellow humans.

To protect yourself – and those in your social and professional networks – be vigilant. Don’t share anything unless you’re sure it’s true. Misinformation warriors are trying to divide American society. Don’t help them. Share wisely.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for our newsletter.[43]]

References

- ^ sow disinformation and social discord (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ share items before even reading them (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ react emotionally, not logically (www.smithsonianmag.com)

- ^ confirms what a person already believes (www.nature.com)

- ^ it’s our own fault (doi.org)

- ^ lies spread faster than truth (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ short-circuit your critical thinking (www.youtube.com)

- ^ after you verify it (theconversation.com)

- ^ emotional contagions (knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu)

- ^ post feel-good stories (www.rollingstone.com)

- ^ inflated self-image (www.brainpickings.org)

- ^ NASA/JPL (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ pope endorsing a U.S. presidential candidate (www.factcheck.org)

- ^ Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ a longstanding philosophical premise (davidhume.org)

- ^ hear something three times (thedecisionlab.com)

- ^ the brain starts (theconversation.com)

- ^ think it’s true (doyouremember.com)

- ^ differing perspectives get ignored (www.journalism.org)

- ^ confirm what we already believe (www.psychologytoday.com)

- ^ identify and acknowledge your biases (www.allsides.com)

- ^ Check out other perspectives (www.allsides.com)

- ^ to get your attention (www.proedit.com)

- ^ Know Your Meme (knowyourmeme.com)

- ^ Memes (www.thrillist.com)

- ^ Ermahgerd (knowyourmeme.com)

- ^ emerging mediums for propaganda (www.vice.com)

- ^ rapidly escalated (www.technologyreview.com)

- ^ extremist groups (www.wired.com)

- ^ “Pepe the frog” meme (www.adl.org)

- ^ attract younger audiences (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ Media Bias/Fact Check website (mediabiasfactcheck.com)

- ^ assess the source yourself (www.allsides.com)

- ^ fairly presenting all the evidence (doi.org)

- ^ count your sharing as a vote (blog.hootsuite.com)

- ^ how truthful particular people are (www.politifact.com)

- ^ old-fashioned critical thinking (libguides.uwlax.edu)

- ^ Media Bias Chart (www.adfontesmedia.com)

- ^ Snopes (www.snopes.com)

- ^ FactCheck (www.factcheck.org)

- ^ meme-checking site (memepoliceman.com)

- ^ harm of sharing misinformation (doi.org)

- ^ Sign up for our newsletter. (theconversation.com)

Authors: H. Colleen Sinclair, Associate Professor of Social Psychology, Mississippi State University

Read more https://theconversation.com/10-ways-to-spot-online-misinformation-132246