New federal sick leave law – who's eligible, who's not and how many weeks do you get

- Written by Elizabeth C. Tippett, Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Oregon

On March 18, President Donald Trump signed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act[1] into law.

The legislation is an emergency intervention to provide paid leave and other support to millions of workers sidelined by school closures, quarantines and caregiving.

An obvious question you’re probably wondering is, “How will it affect me?”

The bad news is that the law does not provide blanket coverage for all workers. Instead, it’s a confusing mess – legislative Swiss cheese, full of exceptions and gradations that affect whether you are covered, for how long and how much pay you can expect to receive.

I study employment law[2] and have combed through the bill to make sense of it. The law also provides[3] emergency funding for unemployment insurance and subsidizes some employer health care premiums, but my focus here is on the core elements pertaining to sick and family leave.

Here’s what I learned.

Small, medium or large

To figure out whether you are covered, the first thing you’ll need to answer is how many people work at your company.

If your employer has 500 or more workers, it is excluded from the new law. Instead, workers at those companies will need to rely on any remaining sick leave benefits available under company policy or state law.

Several states[4], including New York, California and Washington, are also considering emergency legislation tied to the coronavirus pandemic and may offer some relief for workers at these bigger companies. These workers can also make use of the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act[5], which provides for unpaid leave if the employee or a family member falls seriously ill.

In addition, some large employers have made new accommodations for their workers. Walmart, the nation’s largest employer, for example, has extended[6] its sick leave benefits for hourly workers. And coffee chain Starbucks expanded its existing sick leave policy to provide paid leave[7] of up to 26 weeks if an employee contracts COVID-19 and is unable to return to work.

If your company employs fewer than 500 people, you should be covered by the new law. But there’s another exception: Businesses with fewer than 50 employees can make use of a hardship exemption[8] if providing leave might put them out of business.

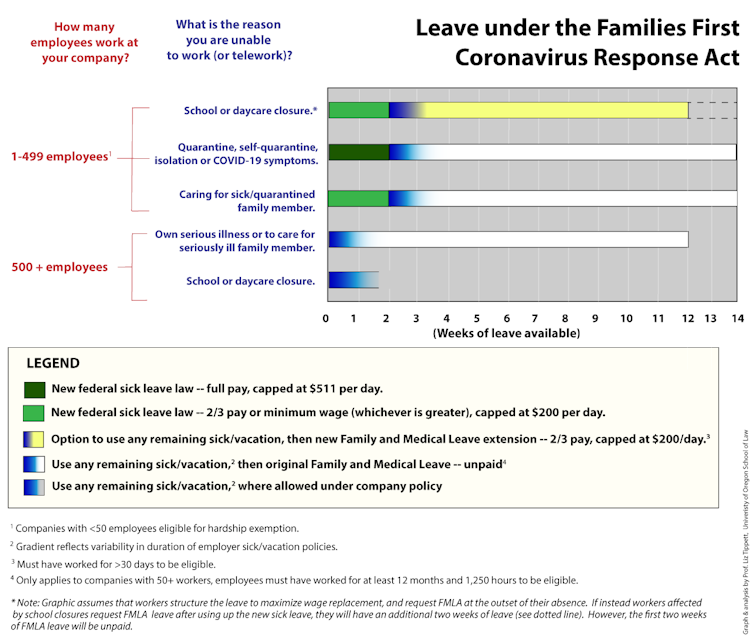

The author created a handy infographic to help explain the new sick leave law.

Elizabeth Tippett

The author created a handy infographic to help explain the new sick leave law.

Elizabeth Tippett

School closures

Assuming your company is covered, the amount of leave available – and how much workers can expect to get paid – will depend on the reason you aren’t able to report to work or do your job remotely.

Here’s where it gets really complicated.

If you are stuck at home due to the closure of a child’s school or day care, you will be eligible for leave under two separate parts of the new law – paid sick leave and family and medical leave.

Congress seems to have structured the law to allow working parents sidelined by a school closure to use both forms of leave at once. Parents would request up to 12 weeks of leave as family and medical leave for a school closure. But since this part of the law doesn’t offer pay until the third week, parents could use the new sick leave provisions to receive income for the first two weeks.

Whether you’re using sick or family leave, you can expect to receive two-thirds of your usual pay, or up to US$200 per day. The money would come directly from your employer who will be reimbursed by tax credits.

Alternatively, people could use the sick leave for the first two weeks and then take 12 weeks under family leave, for a total of 14 weeks, but that would include two weeks that are unpaid.

If you have any available vacation or sick pay under your company’s policy, you may want to use that first since it typically provides full pay.

What happens if you get sick

Workers who are directly affected by the new coronavirus can expect more generous income replacement – but only briefly.

If you are under government-ordered quarantine or isolation, self-isolating at the instruction of a health care provider or experiencing COVID-19 symptoms and seeking a medical diagnosis, you can make use of the new federal sick leave law for up to two weeks. During this time, you should receive your usual pay, capped at $511 per day.

If you become seriously ill beyond two weeks, the new law does not offer additional paid leave. However, you may be eligible to take another 12 weeks of unpaid leave under the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act[9]. This covers only companies with more than 50 people and workers employed there for longer than 12 months. During this time, your job is protected, but you may be required to use any accrued sick leave or vacation available under company policy.

The rules are similar if you are caring for someone who is under government-ordered quarantine or isolation or has been ordered to self-isolate by a health care provider. The only difference is that your income would be only two-thirds of your usual pay, capped at $200 a day, for two weeks.

And again, if you are caring for a family member who becomes seriously ill, you may be able to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave under the 1993 act without losing your job.

In normal times, legislation like this would have been considered broad and ambitious, but as the crisis deepens, its exclusions will likely leave vulnerable workers exposed. With another stimulus bill in the works[10], Congress will have another chance to help Americans whose lives have been turned upside down by this pandemic.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read our newsletter[11].]

References

- ^ Families First Coronavirus Response Act (www.congress.gov)

- ^ study employment law (uonews.uoregon.edu)

- ^ also provides (time.com)

- ^ Several states (www.law360.com)

- ^ Family and Medical Leave Act (www.dol.gov)

- ^ extended (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ paid leave (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ exemption (www.congress.gov)

- ^ 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act (www.dol.gov)

- ^ another stimulus bill in the works (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Read our newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Elizabeth C. Tippett, Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Oregon