How to make presidential debates serve voters, not candidates

- Written by John P. Koch, Senior Lecturer and Director of Debate, Vanderbilt University

Presidential debates are not debates at all[1]. They provide candidates with opportunities to deliver their own pre-scripted messages, largely unchallenged.

Ideally, presidential debate scholars agree, these events should help voters identify which candidate they agree with[2] most on key issues, and, as other academic debate coaches put it, see how a candidate would “make decisions, implement policies, and think through complex problems[3]” if elected.

The debates, as currently structured, do achieve the first goal: Voters can find out which candidate fits[4] with their views. However, the many Democratic presidential primary debates this election cycle have failed to give many a good idea of how any of the candidates would approach hard decisions once in office.

Fortunately, there are better debate formats. I coach debate at Vanderbilt University[5], and three new approaches in the field of competitive academic debate offer ideas that could help presidential debates serve multiple purposes – not just one.

Right now, candidates face journalists – but they could face subject-matter experts instead.

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images[6]

Right now, candidates face journalists – but they could face subject-matter experts instead.

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images[6]

Face a panel of experts

Current presidential debates, based on 1950s game shows[7], put candidates side by side on a stage to answer questions from a panel of journalists and respond to each other’s comments. There is little opportunity for deep questioning, which could reveal much more about candidates’ understanding of complex issues like foreign policy, health care and the economy.

This year, the Vanderbilt debate team started competing in the Civic Debate Conference[8], which tests different debate formats. One, called the Schuman Challenge, requires our students to discuss their ideas with experts[9]. The students are given a problem and asked to write a proposal to solve it, and then present and defend it in front of a group of people who know a lot about that issue. This year, for instance, students are exploring how the United States and the European Union should respond to alternative models of government in China.

This is an intense process[10] that requires exhaustive research, argument preparation, deep knowledge and clear decisions. Our best students excel at this format – and it seems a useful way to test presidential candidates’ ability to study and prepare, then explain and defend their positions on public issues.

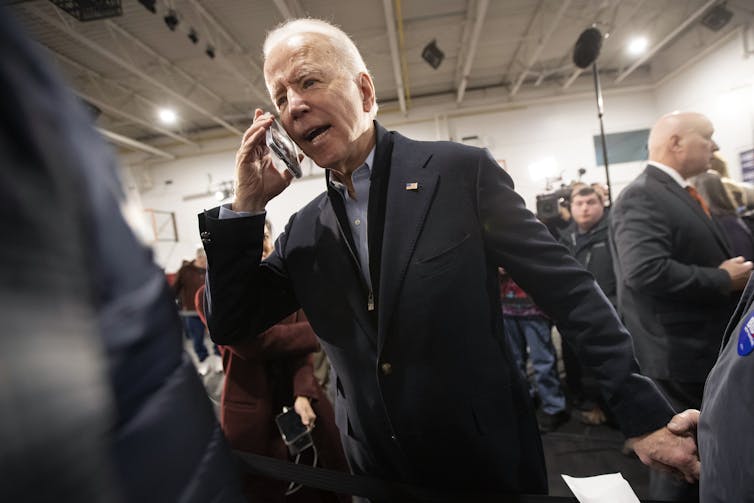

Candidates could phone a friend, or an adviser, to show how they would marshal a team to address a particular issue.

AP Photo/Mary Altaffer[11]

Candidates could phone a friend, or an adviser, to show how they would marshal a team to address a particular issue.

AP Photo/Mary Altaffer[11]

Consult with advisers

Another way to improve current debates would be to include their advisers in the debate process, since presidents often rely on them to make decisions.

At Emory University in 2019, Civic Debate member schools participated in an event[12] about improving voting rights in the United States. First, all the students got information from experts at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights[13]. Then the schools’ teams devised and presented their solutions. After watching all the presentations, each team modified its ideas to reflect others’ proposals, and each presented a revised plan to the group.

For presidential candidates, the format could be adapted so candidates are given a topic, an opportunity to meet with their advisers, and then time to present their solutions. After hearing each other’s ideas, the candidates could then discuss each other’s plans in an attempt to identify the best course of action.

This would allow voters to see how a candidate would collect information, reflect upon disagreements, modify their own proposals and ultimately make a decision.

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, candidates came together to support a cause.

AP Photo/Meg Kinnard[14]

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, candidates came together to support a cause.

AP Photo/Meg Kinnard[14]

Work as a team

A third approach could involve having the candidates work as a team.

Traditionally, academic debate is a team sport, in which each team represents a particular university. However, the Civic Debate Conference has combined multiple schools into single teams[15]. The result is that debaters from various schools must find compromise and arrive at policy positions that all of the team’s members are willing – and able – to defend.

The presidency is not a dictatorship, and the American system of government requires compromise. It would be very revealing to team candidates up with each other – either by choice or randomly – to see how they work through their differences, and ultimately find out what they are willing to defend together.

It’s probably too much to try all three of these potential formats at once. But having multiple debate types over time might sustain the public’s interest. Additional formats would reveal more about candidates, helping help voters make their choices not only about whom they agree with, but whose way of thinking they find most appropriate for the presidency.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter[16].]

References

- ^ Presidential debates are not debates at all (theconversation.com)

- ^ identify which candidate they agree with (www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org)

- ^ make decisions, implement policies, and think through complex problems (www.thewrap.com)

- ^ find out which candidate fits (doi.org)

- ^ I coach debate at Vanderbilt University (as.vanderbilt.edu)

- ^ Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ 1950s game shows (theconversation.com)

- ^ Civic Debate Conference (civicdebateconference.org)

- ^ discuss their ideas with experts (eeas.europa.eu)

- ^ intense process (www.wm.edu)

- ^ AP Photo/Mary Altaffer (www.apimages.com)

- ^ event (civicdebateconference.org)

- ^ National Center for Civil and Human Rights (www.civilandhumanrights.org)

- ^ AP Photo/Meg Kinnard (www.apimages.com)

- ^ combined multiple schools into single teams (civicdebateconference.org)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: John P. Koch, Senior Lecturer and Director of Debate, Vanderbilt University

Read more https://theconversation.com/how-to-make-presidential-debates-serve-voters-not-candidates-122919