Why the extreme reaction to Obamacare could be the new normal in American politics

- Written by Simon F. Haeder, Assistant Professor of Political Science, West Virginia University

It has been more than eight years since the passage of the Affordable Care Act[1]. Many may not remember the tumultuous scenes in Washington, D.C., and around the nation that preceded its passage. Town halls[2] from Iowa to California turned into shouting matches. Signs comparing President Barack Obama to Hitler and Stalin[3] were waved at demonstrations. Angry seniors demanded to “keep your government hands off my Medicare”[4] in protesting the ACA.

Yet, we have seen few signs of abatement since President Obama signed the bill into law. Indeed, just weeks ago, 20 states filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the Affordable Care Act.[5] It seems hardly a week goes by without President Trump attacking his predecessor’s signature accomplishment[6].

One of the hotbeds of resistance can be found in a small group of members of Congress, particularly in the House of Representatives. These legislators have shown little interest in letting up their opposition to kill the law. What is driving this persistence?

Our recent article published in the Journal of Health Policy, Politics, and Law[7] shows that the driving force behind the continued repeal effort has been what political scientists call “intense policy demanders.” These are mobilized activists who use their control of important electoral resources to shape the policy agenda.

Our analysis shows that when it comes to the ACA, extremists have defined the politics of repeal and replace in fundamental ways.

What Republicans have done to make the ACA fail

Opposition to the ACA has been fierce from some groups, even though the law is popular with millions.

txking/Shutterstock.com[8]

Opposition to the ACA has been fierce from some groups, even though the law is popular with millions.

txking/Shutterstock.com[8]

Of course, Republican opposition has not emerged from Congress alone. Many Republican-controlled state legislatures and governors[9] have done their fair share to oppose the implementation of the ACA.

Dozens of lawsuits have been filed[10] seeking to overturn parts or the entirety of the health law. Many states have refused to establish insurance marketplaces or expand their Medicaid program[11].

Various states have passed have prevented state employees from cooperating with the federal government[12] in any implementation activities.

Most recently, states like Idaho[13] and Iowa[14] are seeking to allow the sale of low-quality insurance products prohibited under the ACA.

Since taking office, the Trump administration has also taken a slew of actions[15] seeking to damage and undo much of the ACA.

In a concerted effort[16], administration officials sought to raise uncertainty[17] about the future of the health law by making a slew of false and misleading statements about the ACA.

Next, the Trump administration relaxed oversight of provider networks[18] in the insurance marketplaces to undoing the ACA’s contraception coverage requirements[19].

The withholding of so-called cost-sharing subsidies[20] temporarily threw many of the nation’s insurance markets into turmoil. The markets seem to have stabilized by now. However, actions by the Trump administration to allow the purchase of association-based[21] and short-term[22] health plans may lead to more harm for insurance markets.

Republican opposition in the House

Our research[23] focuses on opposition to the ACA by Republicans in Congress. Unlike opposition in the states and in the courts, this component has gained little scholarly attention so far.

We argue that much of the persistence of Republican resistance can be attributed to intense policy demanders. These ideological extremists include groups like the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity[24], think tanks like the Heritage Foundation[25], and political action committees like Club for Growth Action[26]. They are often intensely focused on a limited set of issues.

Using the resources at their disposal, they support like-minded individuals in return for loyalty commitments. These resources include campaign contributions and endorsements.

The first part of our analysis[27] looks at the introduction of bills seeking to overturn all or part of the ACA.

Our findings show that contributions by businesses are the most important predictor of bill introductions[28] for this part of the repeal effort. This particularly holds for bills seeking major changes to the ACA. The most conservative members[29] of the Republican Party were also the ones seeking to undo the ACA.

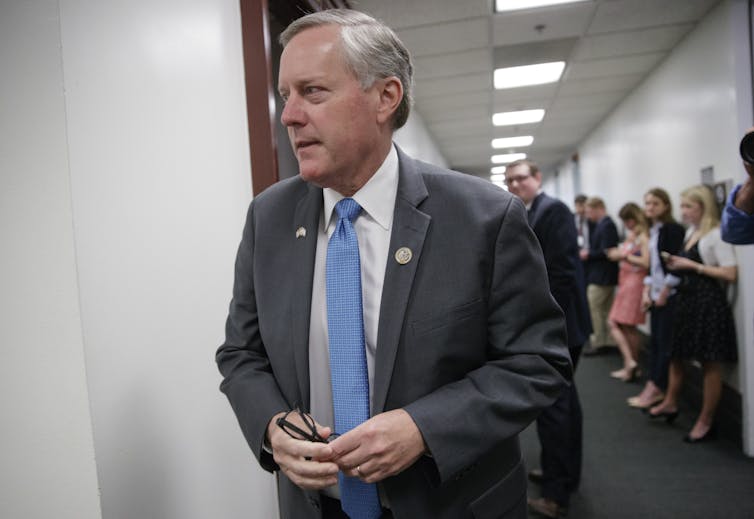

House Freedom Caucus Chairman Mark Meadows, R-N.C., led efforts to pass the American Health Care Act in March 2017.

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite[30]

House Freedom Caucus Chairman Mark Meadows, R-N.C., led efforts to pass the American Health Care Act in March 2017.

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite[30]

The second part of our research[31] analyzed the first major Republican repeal effort under the Trump administration, the American Health Care Act. We particularly looked at the role of the Freedom Caucus[32] because it is the group most aligned with these intense policy demanders.

When it was first introduced in March of 2017, the American Health Care Act[33], proved decidedly too liberal for groups like the Heritage Foundation and Americans for Prosperity. Indeed, they were vocal in their opposition as they referred to it as “Obamacare Lite[34].” As a result, membership in the Freedom Caucus proved the overwhelming predictor[35] of initial Republican opposition.

Seeking to salvage their efforts, Republicans were able to negotiate a compromise by the end of April 2017. The so-called MacArthur amendment allowed states to opt out of almost all the requirements of the ACA. Most of the Freedom Caucus, along with virtually all Republicans[36], eventually voted for the bill.

Although not part of our analysis, the same dynamic of conservative opposition to “Obamacare Lite” also help to explain the inability of Senate leaders to advance their version ACA repeal, the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA)[37]. The key vote on BCRA failed 43-57[38] because it alienated moderates like Sens. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Lisa Murkowski, R-Ark. But it also failed because of opposition from conservative anti-ACA loyalists like Mike Lee, R-Utah,[39] and Rand Paul, R-Ky.[40], who believed the bill did not go far enough in rolling back the ACA.

What we can learn from the Republican opposition to the ACA

Our analysis of Republican resistance to the ACA in Congress holds lessons that go beyond the controversial health law.

The Affordable Care Act came with many flaws[41]. These mishaps inhibited its swift and efficient implementation.

Yet its drafters were limited in what they could have done to stave off Republican opposition. No matter what design choices they would have made, the ACA was to trigger an asymmetric mobilization of ideological extreme partisan policy demanders.

Over the past years, we have seen the growing influence of intensely ideological and well-funded outside groups. As a result, the post-enactment partisan battle surrounding the ACA may become the new normal in American politics.

We believe there’s an important lesson here for policymakers. In a polarized world, policy does not generate political support on its own[42]. Getting policy design decisions right and passing legislation is not enough to see it succeed. Policymakers need to expect persistent opposition and seek to find well-organied political allies beyond the Capitol.

References

- ^ passage of the Affordable Care Act (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Town halls (www.npr.org)

- ^ Signs comparing President Barack Obama to Hitler and Stalin (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ “keep your government hands off my Medicare” (www.huffingtonpost.com)

- ^ 20 states filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the Affordable Care Act. (theconversation.com)

- ^ President Trump attacking his predecessor’s signature accomplishment (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ recent article published in the Journal of Health Policy, Politics, and Law (watermark.silverchair.com)

- ^ txking/Shutterstock.com (www.shutterstock.com)

- ^ Republican-controlled state legislatures and governors (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Dozens of lawsuits have been filed (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ Many states have refused to establish insurance marketplaces or expand their Medicaid program (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ have prevented state employees from cooperating with the federal government (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Idaho (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ Iowa (www.modernhealthcare.com)

- ^ Trump administration has also taken a slew of actions (theconversation.com)

- ^ concerted effort (theconversation.com)

- ^ raise uncertainty (theconversation.com)

- ^ oversight of provider networks (www.fiercehealthcare.com)

- ^ ACA’s contraception coverage requirements (www.cosmopolitan.com)

- ^ cost-sharing subsidies (theconversation.com)

- ^ association-based (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ short-term (www.philly.com)

- ^ Our research (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ Americans for Prosperity (americansforprosperity.org)

- ^ Heritage Foundation (www.heritage.org)

- ^ Club for Growth Action (www.clubforgrowth.org)

- ^ first part of our analysis (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ most important predictor of bill introductions (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ most conservative members (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite (www.apimages.com)

- ^ second part of our research (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ Freedom Caucus (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ American Health Care Act (theconversation.com)

- ^ Obamacare Lite (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ proved the overwhelming predictor (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ virtually all Republicans (read.dukeupress.edu)

- ^ Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) (www.budget.senate.gov)

- ^ failed 43-57 (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Mike Lee, R-Utah, (www.lee.senate.gov)

- ^ Rand Paul, R-Ky. (www.slate.com)

- ^ Affordable Care Act came with many flaws (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ policy does not generate political support on its own (www.degruyter.com)

Authors: Simon F. Haeder, Assistant Professor of Political Science, West Virginia University