Why California gets to write its own auto emissions standards: 5 questions answered

- Written by Nicholas Bryner, Emmett/Frankel Fellow in Environmental Law and Policy, University of California, Los Angeles

Editor’s note: On April 2, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt announced[1] that the Trump administration plans to revise tailpipe emissions standards negotiated by the Obama administration for motor vehicles built between 2022 and 2025, saying the standards were set “too high.” Pruitt also said the EPA was re-examining California’s historic ability to adopt standards that are more ambitious than the federal government’s. Legal scholars Nicholas Bryner and Meredith Hankins explain why California has this authority – and what may happen if the EPA tries to curb it.

Where does California get this special authority?

The Clean Air Act empowers the EPA to regulate air pollution from motor vehicles. To promote uniformity, the law generally bars states from regulating car emissions.

But when the Clean Air Act was passed, California was already developing innovative laws and standards to address its unique air pollution problems. So Congress carved out an exemption. As long as California’s standards protect public health and welfare at least as strictly as federal law, and are necessary “to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions,” the law requires[2] the EPA to grant California a waiver so it can continue to apply its own regulations. California has received numerous waivers[3] as it has worked to reduce vehicle emissions by enacting ever more stringent standards since the 1960s.

Other states can’t set their own standards, but they can opt to follow California’s motor vehicle emission regulations. Currently, 12 states and the District of Columbia[4] have adopted California’s standards.

Gov. Ronald Reagan signs legislation establishing the California Air Resources Board to address the state’s air pollution, August 30, 1967.

CA ARB[5]

Gov. Ronald Reagan signs legislation establishing the California Air Resources Board to address the state’s air pollution, August 30, 1967.

CA ARB[5]

What are the “compelling and extraordinary conditions” that California’s regulations are designed to address?

In the 1950s scientists recognized[6] that the unique combination of enclosed topography, a rapidly growing population and a warm climate in the Los Angeles air basin was a recipe for dangerous smog. Dutch chemist Arie Jan Haagen-Smit[7] discovered in 1952 that worsening Los Angeles smog episodes were caused by photochemical reactions between California’s sunshine and nitrogen oxides and unburned hydrocarbons in motor vehicle exhaust.

California’s Motor Vehicle Pollution Control Board issued regulations[8] mandating use of the nation’s first vehicle emissions control technology in 1961, and developed the nation’s first vehicle emissions standards in 1966. Two years later the EPA adopted standards identical to California’s for model year 1968 cars. UCLA Law scholar Ann Carlson calls this pattern, in which California innovates and federal regulators piggyback on the state’s demonstrated success, “iterative federalism[9].” This process has continued for decades.

California’s severe air pollution problems have made it a pioneer in air quality research.California has set ambitious goals[10] for slowing climate change. Is that part of this dispute with the EPA?

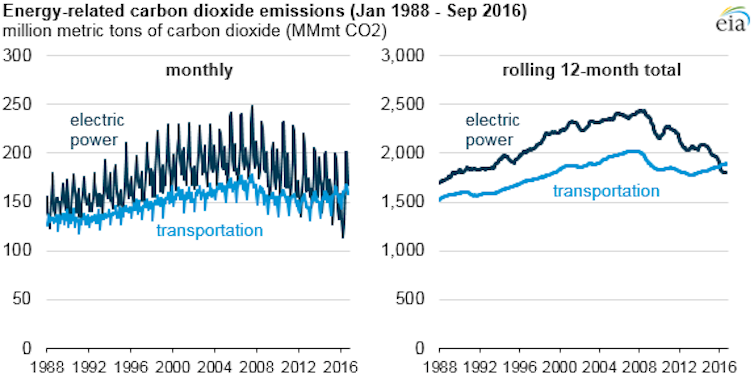

Yes. Transportation is now the largest source[11] of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the United States. The tailpipe standards that the Obama EPA put in place were designed to limit GHG emissions from cars by improving average fuel efficiency.

These standards were developed jointly by the EPA, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and California, which have overlapping legal authority to regulate cars. EPA and California have the responsibility to control motor vehicle emissions of air pollutants, including GHGs. DOT is in charge of regulating fuel economy[12].

Congress began regulating fuel economy in response to the oil crisis in the 1970s. DOT sets the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard[13] that each auto manufacturer must meet. Under this program, average fuel economy in the United States improved in the late 1970s but stagnated[14] from the 1980s to the early 2000s as customers shifted to purchasing larger vehicles, including SUVs, minivans and trucks.

In 2007 Congress responded with a new law that required DOT to set a standard of at least 35 miles per gallon by 2020, and the “maximum feasible average fuel economy” after that. That same year, the Supreme Court ruled[15] that the Clean Air Act authorized the EPA to regulate GHG emissions from cars.

The Obama administration’s tailpipe standard brought these overlapping mandates together. EPA’s regulation sets how much carbon dioxide can be emitted per mile, which matches with DOT’s increased standard for average fuel economy. It also includes a “midterm review” to assess progress. Administrator Scott Pruitt’s new EPA review[16], released on April 2, overturned the Obama administration’s midterm review and concluded that the 2022 to 2025 standard was not feasible.

The EPA now argues[17] that earlier assumptions behind the rule were “optimistic” and can’t be met. However, its review almost entirely ignored the purpose of the standards and the costs of continuing to emit GHGs at high levels. Although the document is 38 pages long, the word “climate” never appears, and “carbon” appears only once.

The EPA’s decision does not yet have any legal impact. It leaves the current standards in place until the EPA and DOT decide on a less-stringent replacement.

U.S. carbon dioxide emissions from transportation exceeded those from electric power generation in 2016 for the first time since the 1970s.

USEIA[18]

U.S. carbon dioxide emissions from transportation exceeded those from electric power generation in 2016 for the first time since the 1970s.

USEIA[18]

Can the Trump administration take away California’s authority to set stricter targets?

The EPA has never attempted to revoke an existing waiver. In 2007, under George W. Bush, the agency denied[19] California’s request for a waiver to regulate motor vehicle GHG emissions. California sued, but the EPA reversed course under President Obama and granted the state a waiver before the case was resolved.

California’s current waiver[20] was approved in 2013 as a part of a “grand bargain[21]” between California, federal agencies and automakers. It covers the state’s Advanced Clean Cars program and includes standards to reduce conventional air pollutants like carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter, as well as the GHG standards jointly developed with the EPA and DOT.

The Trump administration is threatening to revoke this waiver when it decouples the national GHG vehicle standards from California’s standards. EPA Administrator Pruitt has said[22] that the agency is re-examining the waiver, and that “cooperative federalism doesn’t mean that one state can dictate standards for the rest of the country.” In our view, this statement mischaracterizes how the Clean Air Act works. Other states have voluntarily chosen to follow California’s rules because they see benefits in reducing air pollution.

How would California respond if the EPA revokes its waiver?

Gov. Jerry Brown[23], Attorney General Xavier Becerra[24] and California Air Resources Board Chair Mary Nichols[25] have all made clear that the state will push back. It’s almost certain that any attempt to revoke or weaken California’s waiver will immediately be challenged in court – and that this would be a major legal battle[26].

References

- ^ announced (www.epa.gov)

- ^ requires (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ numerous waivers (www.epa.gov)

- ^ 12 states and the District of Columbia (database.aceee.org)

- ^ CA ARB (ww2.arb.ca.gov)

- ^ recognized (doi.org)

- ^ Arie Jan Haagen-Smit (www.arb.ca.gov)

- ^ regulations (www.arb.ca.gov)

- ^ iterative federalism (papers.ssrn.com)

- ^ set ambitious goals (theconversation.com)

- ^ largest source (e360.yale.edu)

- ^ regulating fuel economy (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ (CAFE) standard (www.nhtsa.gov)

- ^ stagnated (nepis.epa.gov)

- ^ ruled (www.law.cornell.edu)

- ^ new EPA review (www.epa.gov)

- ^ argues (www.epa.gov)

- ^ USEIA (www.eia.gov)

- ^ denied (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ current waiver (www.gpo.gov)

- ^ grand bargain (obamawhitehouse.archives.gov)

- ^ said (www.epa.gov)

- ^ Gov. Jerry Brown (twitter.com)

- ^ Attorney General Xavier Becerra (oag.ca.gov)

- ^ California Air Resources Board Chair Mary Nichols (ww2.arb.ca.gov)

- ^ major legal battle (legal-planet.org)

Authors: Nicholas Bryner, Emmett/Frankel Fellow in Environmental Law and Policy, University of California, Los Angeles