Microwaving sewage waste may make it safe to use as fertilizer on crops

- Written by Gang Chen, Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Florida State University

My team has discovered another use for microwave ovens that will surprise you.

Biosolids – primarily dead bacteria – from sewage plants are usually dumped into landfills. However, they are rich in nutrients and can potentially be used as fertilizers. But farmers can’t just replace the normal fertilizers they use on agricultural soil with these biosolids. The reason is that they are often contaminated with toxic heavy metals like arsenic, lead, mercury and cadmium from industry. But dumping them in the landfills is wasting precious resources. So, what is the solution?

I’m an environmental engineer[1] and an expert in wastewater treatment. My colleagues and I have figured out how to treat these biosolids and remove heavy metals so that they can be safely used as a fertilizer.

How treatment plants clean wastewater

Wastewater contains organic waste such as proteins, carbohydrates, fats, oils and urea, which are derived from food and human waste we flush down in kitchen sinks and toilets. Inside treatment plants, bacteria decompose these organic materials, cleaning the water which is then discharged to rivers, lakes or oceans.

The bacteria don’t do the work for nothing. They benefit from this process by multiplying as they dine on human waste. Once water is removed from the waste, what remains is a solid lump of bacteria called biosolids.

This is complicated by the fact that wastewater treatment plants accept not only residential wastewater but also industrial wastewater, including the liquid that seeps out of solid waste in landfills – called leachate – which is contaminated with toxic metals including arsenic, lead, mercury and cadmium. During the wastewater treatment process, heavy metals are attracted to the bacteria and accumulate on their surfaces.

If farmers apply the biosolids at this stage, these metals will separate from the biosolids and contaminate the crop for human consumption. But removing heavy metals isn’t easy because the chemical bonds between heavy metals and biosolids are very strong.

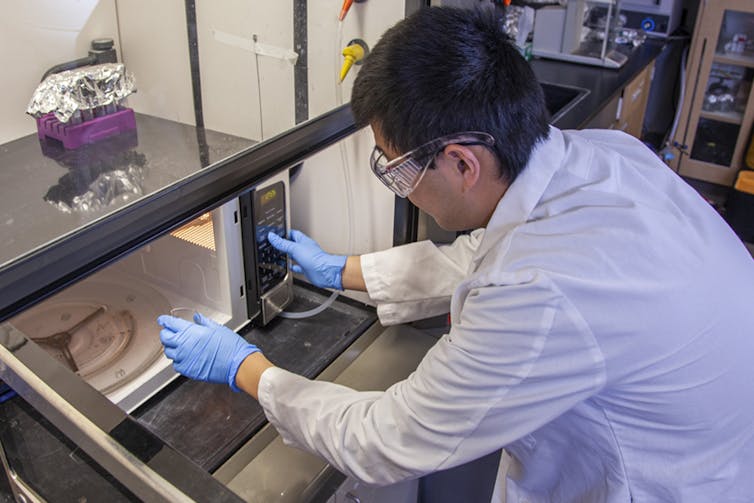

Gang Chen microwaves some biosolids, separating the organic material from the toxic metals.

Gang Chen/FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, CC BY-SA[2]

Gang Chen microwaves some biosolids, separating the organic material from the toxic metals.

Gang Chen/FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, CC BY-SA[2]

Microwaving waste releases heavy metals

Conventionally, these metals are removed from biosolids using chemical methods involving acids, but this is costly and generates more dangerous waste. This has been practiced on a small scale in some agricultural fields.

After a careful calculation of the energy requirement to release the heavy metals from the attached bacteria, I searched around for all the possible energy sources that can provide just enough to break the bonds but not too much to destroy the nutrients in the biosolids. That’s when I serendipitously noticed the microwave oven in my home kitchen and began to wonder whether microwaving was the solution.

My team and I tested whether microwaving the biosolids would break the bonds between heavy metals and the bacterial cells. We discovered it was efficient and environmentally friendly. The work has been published in the Journal of Cleaner Production[3]. This concept can be adapted to an industrial scale by using electromagnetic waves to produce the microwaves.

This is a solution that should be beneficial for many people. For instance, managers of wastewater treatment plants could potentially earn revenue by selling the biosolids instead of paying disposal fees for the material to be dumped to the landfills.

It is a better strategy for the environment because when biosolids are deposited in landfills, the heavy metals seep into landfill leachate, which is then treated in wastewater treatment plants. The heavy metals thus move between wastewater treatment plants and landfills in an endless loop. This research breaks this cycle by separating the heavy metals from biosolids and recovering them. Farmers would also benefit from cheap organic fertilizers that could replace the chemical synthetic ones, conserving valuable resources and protecting the ecosystem.

Is this the end? Not yet. So far we can only remove 50% of heavy metals but we hope to shift this to 80% with improved experimental designs. My team is currently conducting small laboratory and field experiments to explore whether our new strategy will work on a large scale. One lesson I would like to share with everyone: Be observant. For any problem, the solution may be just around you, in your home, your office, even in the appliances you are using.

Biosolids after collection from a waste treatment facility.

Gang Chen/FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, CC BY-SA[4]

Biosolids after collection from a waste treatment facility.

Gang Chen/FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, CC BY-SA[4]

[ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day.[5] ]

References

- ^ I’m an environmental engineer (www.eng.fsu.edu)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ published in the Journal of Cleaner Production (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day. (theconversation.com)

Authors: Gang Chen, Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Florida State University