Parents of medically fragile children and their kids could use help, understanding year-round

- Written by Katherine Rafferty, Assistant Teaching Professor, Iowa State University

December is a prime time to fundraise for children’s hospitals and other charities, as people want to give back and help sick children throughout the holiday season.

But for children who live with chronic health problems, their issues extend beyond the holidays. And, just as the kids have medical needs, their parents have needs too. Theirs are often unmet and muted.

I have spent seven years researching the needs of these parents, particularly mothers of children living with medical complexities.

Studying these parents’ experiences is important because they experience a great deal of stress and often have unmet personal needs that harm their marriage and families[1]. About 17% of parents[2] feel their health has worsened since their child’s diagnosis, and three out of 10 caregivers[3] report feelings of chronic sorrow.

These parents are also four times more likely[4] to experience post-traumatic stress disorder than parents with healthy children. While some things have improved for these parents, many challenges persist, including a lack of communication and care coordination that includes their needs.

More kids than you might imagine

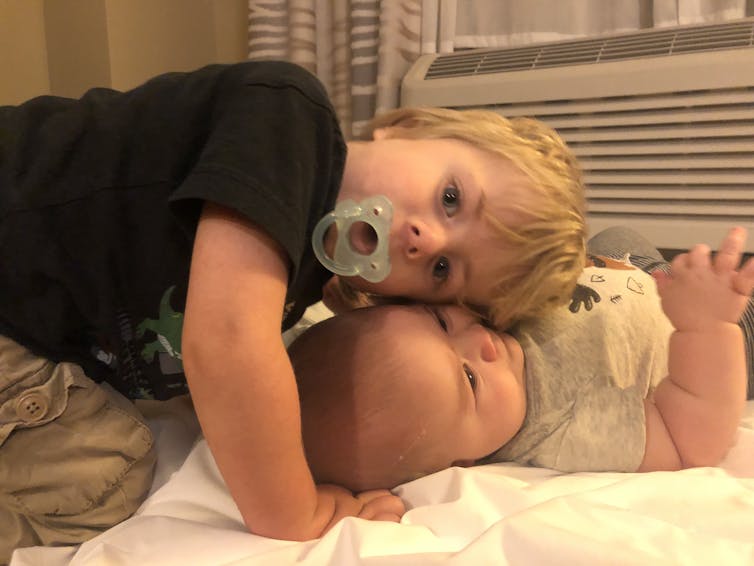

Alex Buck plays with his younger brother Silas in October 2019.

Katie Buck, CC BY-ND[5]

Alex Buck plays with his younger brother Silas in October 2019.

Katie Buck, CC BY-ND[5]

About 10% of children[6] admitted to hospitals in any given year live with ongoing, serious medical issues. Some of these conditions include cerebral palsy, heart disease, cancer, cystic fibrosis and mental illness.

For many of these children, it’s not their first visit to the hospital. Sometimes, the hospital visit is routine. The frequency of these visits tends to increase during cold and flu season, which often coincides with the holidays.

The medical expenses to care for these 13%-18% of U.S. children[7] account for about one-third of total U.S. health care spending dollars for all children living in the U.S., or about US$100 billion a year.

In 2014, over 16% of U.S. public schools[8] had at least one medically complex child.

And, the number of children living with medical complexities is increasing[9]. Therapies and treatments have been discovered for diseases and congenital abnormalities that once were life-threatening. Advances in science and technology have contributed to a new generation of children[10] who have survived an abnormality, but who still have severe medical issues that impact daily living.

Many of these children will be cared for in community settings, attending schools or outpatient clinics for treatments and therapies. Because of the challenges and difficulties associated with care coordination, these children and their parents are at risk for health care inequities and poor health outcomes[11].

Parents as case managers

Alex Buck with his father, Ryan Buck.

Katie Buck, CC BY-ND[12]

Alex Buck with his father, Ryan Buck.

Katie Buck, CC BY-ND[12]

Parents, particularly mothers, have a critical role that directly affects their child’s quality of life. Parents are often the only consistent person[13] managing a child’s complex medical condition. Therefore, a child’s quality of life is largely dependent upon their parent’s advocacy efforts[14]. Research shows that parents with medically complex children want their child’s whole person treated[15], not just the physical or mental aspects.

A recent study found that children with medical complexities are cared for by an average of 13 outpatient physicians[16] and six subspecialists. Therefore, managing a child’s treatment and maintaining her or his quality of life is often challenging and costly for parents.

I have worked in collaboration with the Ronald McDonald House Charities of Eastern Wisconsin[17] and the SHINE[18] pediatric palliative care program affiliated with UnityPoint Health-Des Moines to interview parents. Across this research, I have found that many parents feel a moral obligation to become advocates[19] for their child.

Advocacy is a complex communicative process that involves establishing roles and responsibilities across different team members, fostering relationships within one’s social network, and remaining educated and informed about their child’s illness. It can be a cumbersome, stigmatizing, isolating and emotionally difficult endeavor.

A need for a normal life

Parents’ responsibilities as advocates for their child require effective communication work[20]. Parents must manage their child’s health information alongside daily physical cares. Different factors influence parents’ decisions about whom to share their child’s private health information[21] with. This means that parents have different reasons or motivations for sharing information with others about their child’s condition.

Parents are often open with family members and friends in order to create a family’s new normal post-diagnosis[22]. One way that parents achieve this is by participating in online advice-giving communities[23] with other parents where they seek informational and emotional support. Other parents with children who have similar medical complexities often proffer helpful advice[24].

Yet, a critical unmet need[25] for achieving normality is a system of helpful support for both parents and their children outside of the hospital setting. For example, only 2%[26] of hospitalized children with complex chronic conditions receive access to post-acute care or home care.

Parents need rest and respite

And then there are the overlooked needs of the parents. Many cite a lack of high-quality respite care, or short-term relief from caring for their sick child. A large national study found that one out of four parents with medically complex children had unmet respite care needs[27]. Respite care is vital for reducing parents’ day-to-day stresses and giving them time to rest and attend to their other responsibilities, such as work and parenting other children.

Parents often have a difficult time finding people whom they trust and who are willing to provide safe, high-quality care in their absence. Family and friends can assist parents by being trained and offering parents this personal time. Parents could also use assistance with running errands, doing yardwork, or making a meal. Parents also report that compliments, messages of encouragement and words of affirmation are helpful.

Open communication is critical to understanding these parents’ support needs and preferences. It is important to recognize that parents may have unique privacy rules and boundaries[28] when seeking support from others. Parents want to collaboratively work with their child’s medical team and be heard and respected. Parents need family and friends to help them maintain their new normal. Finally, they need to be connected with other parents like them to receive access to critical advice and emotional support.

[ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day.[29] ]

References

- ^ marriage and families (doi.org)

- ^ 17% of parents (www.aarp.org)

- ^ three out of 10 caregivers (doi.org)

- ^ four times more likely (blog.cincinnatichildrens.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ 10% of children (doi.org)

- ^ 13%-18% of U.S. children (doi.org)

- ^ over 16% of U.S. public schools (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ increasing (doi.org)

- ^ new generation of children (doi.org)

- ^ health care inequities and poor health outcomes (www.aap.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ only consistent person (doi.org)

- ^ parent’s advocacy efforts (doi.org)

- ^ want their child’s whole person treated (doi.org)

- ^ are cared for by an average of 13 outpatient physicians (doi.org)

- ^ Ronald McDonald House Charities of Eastern Wisconsin (rmhc-easternwi.org)

- ^ SHINE (www.unitypoint.org)

- ^ advocates (doi.org)

- ^ communication work (doi.org)

- ^ private health information (doi.org)

- ^ post-diagnosis (nsuworks.nova.edu)

- ^ online advice-giving communities (doi.org)

- ^ helpful advice (doi.org)

- ^ a critical unmet need (pediatrics.aappublications.org)

- ^ 2% (www.lpfch.org)

- ^ had unmet respite care needs (doi.org)

- ^ unique privacy rules and boundaries (doi.org)

- ^ Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter and get a digest of academic takes on today’s news, every day. (theconversation.com)

Authors: Katherine Rafferty, Assistant Teaching Professor, Iowa State University