Planetary confusion -- why astronomers keep changing what it means to be a planet

- Written by Christopher Palma, Associate Dean for Undergraduate Students and Teaching Professor of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Pennsylvania State University

As an astronomer, the question I hear the most is why isn’t Pluto a planet anymore? More than 10 years ago, astronomers famously voted to change Pluto’s classification[1]. But the question still comes up.

When I am asked directly if I think Pluto is a planet, I tell everyone my answer is no. It all goes back to the origin of the word “planet.” It comes from the Greek phrase for “wandering stars.” Back in ancient times before the telescope was invented, the mathematician and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy called stars “fixed stars” to distinguish them from the seven wanderers that move across the sky in a very specific way. These seven objects are the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn[2].

When people started using the word “planet,” they were referring to those seven objects. Even Earth was not originally called a planet – but the Sun and Moon were.

Since people use the word “planet” today to refer to many objects beyond the original seven, it’s no surprise we argue about some of them.

Although I am trained as an astronomer and I studied more distant objects like stars and galaxies, I have an interest in the objects in our Solar System because I teach several classes on planetary science.

Asteroids, the first demoted planets

The word “planet” is used to describe Uranus and Neptune[3], which were discovered in 1781 and 1846 respectively, because they move in the same way that the other “wandering stars” move. Like Saturn and Jupiter, if you look at them through a telescope, they appear bigger than stars, so they were recognized to be more like planets than stars.

Not long after the discovery of Uranus, astronomers discovered additional wandering objects – these were named Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta[4]. At the time they were considered planets, too. Through a telescope they look like pinpoints of light and not disks. With a small telescope, even distant Neptune appears fuzzier than a star[5]. Even though these other, new objects were called planets at first, astronomers thought they needed a different name since they appear more star-like than planet-like.

William Herschel (who discovered Uranus) is often said to have named them “asteroids” which means “star-like,” but recently, Clifford Cunningham[6] claimed that the person who coined that name was Charles Burney Jr., a preeminent Greek scholar.

Today, just like the word “planet,” we use the word “asteroid” differently. Now it refers to objects that are rocky in composition, mostly found between Mars and Jupiter, mostly irregularly shaped, smaller than planets, but bigger than meteoroids. Most people assume there is a strict definition for what makes an object an asteroid. But there isn’t, just like there never was for the word “planet.”

In the 1800s the large asteroids were called planets. Students at the time likely learned that the planets were Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Ceres, Vesta, Pallas, Juno, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and, eventually, Neptune. Most books today write that asteroids are different than planets, but there is a debate among astronomers[7] about whether the term “asteroid” was originally used to mean a small type of planet, rather than a different type of object altogether.

How are moons different than planets?

These days, scientists consider properties of these celestial objects to figure out whether an object is a planet or not. For example, you might say that shape is important; planets should be mostly spherical, while asteroids can be lumpy. As astronomers try to fix these definitions to make them more precise, we then create new problems. If we use roundness as an important distinction for objects, what should we call moons? Should moons be considered planets if they are round and asteroids if they are not round? Or are they somehow different from planets and asteroids altogether?

I would argue we should again look to how the word “moon” came to refer to objects that orbit planets.

When astronomers talk about the Moon of Earth, we capitalize the word “Moon” to indicate that it’s a proper name. That is, the Earth’s moon has the name, Moon[8]. For much of human history, it was the only Moon known, so there was no need to have a word that referred to one celestial body orbiting another. This changed when Galileo discovered four large objects orbiting Jupiter[9]. These are now called Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, the moons of Jupiter.

This makes people think the technical definition of moon is a satellite of another object, and so we call lots of objects that orbit Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, Eris, Makemake, Ida and a large number of other asteroids[10] moons. When you start to look at the variety of moons, some, like Ganymede and Titan, are larger than Mercury. Some are similar in size to the object they orbit. Some are small and irregularly shaped, and some have odd orbits.

So they are not all just like Earth’s Moon. If we try to fix the definition for what is a moon and how that differs from a planet and asteroid, we are likely going to have to reconsider the classification of some of these objects, too. You can argue that Titan has more properties in common with the planets than Pluto does, for example. You can also argue that every single particle in Saturn’s rings is an individual moon, which would mean that Saturn has billions upon billions of moons.

Family portrait of Pluto’s moons: This composite image shows a sliver of Pluto’s large moon, Charon, and all four of Pluto’s small moons.

NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI[11]

Family portrait of Pluto’s moons: This composite image shows a sliver of Pluto’s large moon, Charon, and all four of Pluto’s small moons.

NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI[11]

Planets around other stars

The most recent naming challenge astronomers face arose when they discovering planets far from our Solar System orbiting around distant stars. These objects have been called extrasolar planets, exosolar planets or exoplanets[12].

Astronomers are currently searching for exomoons[13] orbiting exoplanets. Exoplanets are being discovered that have properties unlike the planets in our Solar System, so astronomers have started putting them in categories like “hot Jupiter,” “warm Jupiter,” “super-Earth” and “mini-Neptune.”

Ideas for how planets form also suggest that there are planetary objects that have been flung out of orbit from their parent star. This means there are free-floating planets[14] not orbiting any star. Should planetary objects that are flung out of a solar system also get ejected from the elite club of planets?

When I teach, I end this discussion with a recommendation. Rather than arguing over planet, moon, asteroid and exoplanet, I think we need to do what Herschel and Burney did and coin a new word. For now, I use “world” in my class, but I do not offer a rigorous definition of what makes something a world and what does not. Instead, I tell my students that all of these objects are of interest to study.

The Sun was once a planet

A lot of people seem to feel that scientists wronged Pluto by changing its classification. I look at it that Pluto was only originally called a planet because of an accident; scientists were looking for planets beyond Neptune, and when they found Pluto they called it a planet, even though its observable properties should have led them to call it an asteroid.

As our understanding of this object has grown, I feel like the evidence now leads me to call Pluto something besides planet. There are other scientists who disagree, feeling Pluto still should be classified as a planet.

But remember: The Greeks started out calling the Sun a planet given how it moved on the sky. We now know that the properties of the Sun show it to belong in a very different category from the planets; it’s a star, not a planet. If we can stop calling the Sun a planet, why can’t we do the same to Pluto?

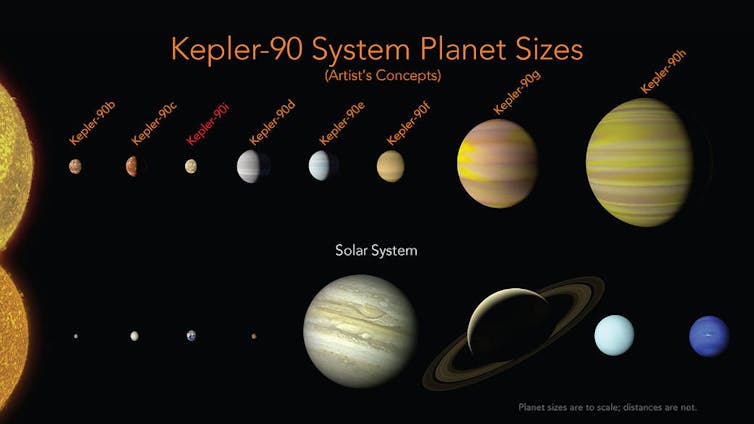

The Kepler-90 planets have a similar configuration to our solar system with small planets found orbiting close to their star, and the larger planets found farther away.

NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel[15]

The Kepler-90 planets have a similar configuration to our solar system with small planets found orbiting close to their star, and the larger planets found farther away.

NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel[15]

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter[16]. ]

References

- ^ Pluto’s classification (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ These seven objects are the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn (www.loc.gov)

- ^ Uranus and Neptune (www.skyandtelescope.com)

- ^ Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta (www.esa.int)

- ^ distant Neptune appears fuzzier than a star (www.astronomy.com)

- ^ recently, Clifford Cunningham (www.skyandtelescope.com)

- ^ debate among astronomers (arxiv.org)

- ^ the Earth’s moon has the name, Moon (curious.astro.cornell.edu)

- ^ Galileo discovered four large objects orbiting Jupiter (galileo.rice.edu)

- ^ large number of other asteroids (stardate.org)

- ^ NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI (www.nasa.gov)

- ^ exoplanets (exoplanets.org)

- ^ exomoons (arxiv.org)

- ^ free-floating planets (exoplanets.nasa.gov)

- ^ NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel (www.nasa.gov)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Christopher Palma, Associate Dean for Undergraduate Students and Teaching Professor of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Pennsylvania State University