Spies and the White House have a history of running wild without congressional oversight

- Written by Charles Tiefer, Professor of Law, University of Baltimore

At the heart of the current crisis over President Donald Trump’s dealings with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy[1] is an intelligence whistleblower[2] whose information has finally made it into public view.

The whistleblower’s complaint about Trump’s interaction with Zelenskiy was initially withheld from the House Intelligence Committee[3], something which the committee chairman protested was a violation of the law.

The complaint was ultimately turned over[4] after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced an impeachment inquiry of the president[5] and almost two weeks after the committee subpoenaed[6] it, and after the Senate had passed a unanimous resolution[7] to provide the complaint to Congress.

For decades now, the evolving role of congressional oversight of U.S. intelligence has involved major clashes and scandals, from the Iran-Contra affair of the 1980s[8] to the intelligence abuses that led to the 2003 war in Iraq[9].

Central to all of these clashes are attempts by intelligence agencies, the president and the executive branch to withhold damning information from Congress. Another common element is the use of civilians to carry out presidential or intelligence agency agendas.

Coups and assassinations

“Intelligence” is the government’s term for collection of information of military or diplomatic value. After World War II, large, new agencies – the CIA[10] and the National Security Agency[11] – were established[12] to conduct information gathering and secret operations.

From the aftermath of World War II to the 1970s, there was virtually no congressional oversight[13] of this intelligence apparatus[14]. And there was only intermittent presidential direction[15]. During the Cold War, intelligence was considered too sensitive for Congress to know.

Some of the agencies’ intelligence work, called “covert activities,” was not mere information-gathering. And some of the activities undertaken by these agencies[16] had a profound impact around the world – without U.S. democratic institutions playing a role.

For example, in 1953 the CIA overthrew the democratically elected leader of Iran[17], Mohammad Mossadegh, and installed in his place the shah, an autocrat who proved happy to do what the U.S. wanted.

The public and Congress had little or no awareness that the CIA[18] engineered this.

In the 1970s, between information uncovered in the Watergate hearings[19] and some key investigative journalism[20], the lid blew off the intelligence agency’s secrecy about the CIA’s many covert interventions both in other countries’ affairs and in the U.S.[21]

A special temporary committee headed by Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho)[22] was established[23] in 1975[24] to explore “the extent, if any, to which illegal, improper, or unethical activities were engaged in by any agency of the Federal Government.”

The activities uncovered included various unsuccessful attempts to kill Fidel Castro[25], the communist leader of Cuba. The CIA’s plans for Castro’s assassination included help from organized crime figures like Santo Trafficante and other people who were not U.S. government officials. Rudy Giuliani is not an organized crime figure, but he’s similar in that he’s a civilian involved in foreign affairs[26]: in this case, the president’s dealings with Ukraine.

The Church Committee discovered[27] CIA plots that were known by presidents; they discovered some that were not. None was known by Congress. The very idea that intelligence agencies could plot overthrowing or murdering foreign leaders[28] without congressional oversight flabbergasted lawmakers[29].

A meeting of the Church Committee, 1975.

AP Photo/Henry Griffin[30]

A meeting of the Church Committee, 1975.

AP Photo/Henry Griffin[30]

Keeping Congress informed

The Church Committee and its sister committee in the House[31] recommended a major reform: the creation of House[32] and Senate Intelligence Committees[33] that would have oversight over intelligence agency activities.

These oversight committees were to be kept fully and currently informed by the intelligence agencies[34]. Nothing was to be withheld from Congress.

The notion that President Trump could force a Ukrainian government investigation of Joe Biden, and that this would be withheld from the House Intelligence Committee, directly contradicts the imperative of congressional oversight[35] established by Congress in the late 1970s.

In the 1980s, the House Intelligence Committee faced one of its greatest challenges – the Iran-Contra affair[36]. President Reagan had kept secret from the committee that he had approved arms-for-hostage deals with Iran and used the proceeds for resupplying arms to the Contras, who were opponents of the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua.

These covert measures fulfilled some of Reagan’s major foreign policy goals. They were not matters of personal political benefit for the president, as the Ukraine affair represents with Trump[37]. When the scandal broke from news about hostage-trading and about a plane crash in the Contra resupply operation, the House formed an Iran-Contra investigating committee[38]. I was special deputy chief counsel of that committee, which was a select committee drawn in part from the House Intelligence Committee.

The Iran-Contra initiatives, although led by Oliver North[39] of the national security staff, also relied on civilians to carry out plans, not unlike Rudy Giuliani. These were Richard Secord, with a military background, and Albert Hakim[40], an accountant who spoke fluent Persian.

Such private figures have enormous power by virtue of their connection to the White House while simultaneously being exempt from routine public sector oversight by congressional intelligence committees.

Donald Regan, President Reagan’s chief of staff, testifies before the Iran-Contra Committee in 1987.

AP Photo/Lana Harris[41]

Donald Regan, President Reagan’s chief of staff, testifies before the Iran-Contra Committee in 1987.

AP Photo/Lana Harris[41]

Scrutiny grows

After 9/11, when al-Qaida terrorists destroyed the World Trade Center[42], the CIA and President George W. Bush came under congressional scrutiny for how much they had known in advance – and ignored[43].

Initially, they were reluctant to divulge what they knew, much like Trump at first fought oversight about his talks with Zelenskiy.

But eventually it came out that President Bush’s daily briefing from the intelligence community had warned[44] of plots to crash airplanes into buildings.

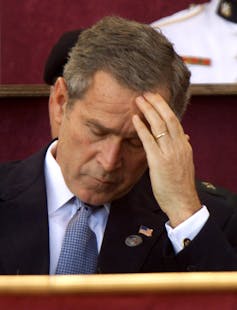

Bush attended a memorial for the people killed on Sept. 11, 2001.

Reuters/Kevin Lamarque[45]

Bush attended a memorial for the people killed on Sept. 11, 2001.

Reuters/Kevin Lamarque[45]

In 2002 came what many consider[46] one of the greatest abuses of intelligence. President Bush and Vice President Richard Cheney bent the CIA’s intelligence reporting to support a United States invasion[47] of Iraq. Internally, the CIA knew its intelligence was extremely weak about whether Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.

But the CIA served Bush and Cheney and made the public case to invade Iraq. Only after the war was over could the House Intelligence Committee penetrate the secretiveness of the CIA and find out the case for the Iraq war was built on foundations like the extremely dubious tales of the informant known as “Curveball[48].”

Presidential accountability

What can be learned from history about the Ukraine scandal?

One lesson is the enormous struggle Congress in general, and the House Intelligence Committee in particular, has waged to exercise democratic accountability over presidential actions. That accountability is made impossible when private citizens – Richard Secord, Albert Hakim, Rudy Giuliani – are used by presidents to carry out foreign affairs.

Another lesson is the power of the CIA to withhold from Congress what it knows would embarrass the president.

And yet another lesson is the disastrous foreign affairs repercussions when the intelligence system is abused by presidents.

The Ukraine affair is the latest intelligence crisis in the troubled control of foreign affairs by the representatives of the American public.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter[49]. ]

References

- ^ President Donald Trump’s dealings with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ intelligence whistleblower (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ withheld from the House Intelligence Committee (intelligence.house.gov)

- ^ turned over (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ impeachment inquiry of the president (www.youtube.com)

- ^ after the committee subpoenaed (intelligence.house.gov)

- ^ passed a unanimous resolution (www.rollcall.com)

- ^ Iran-Contra affair of the 1980s (www.britannica.com)

- ^ intelligence abuses that led to the 2003 war in Iraq (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ the CIA (www.cia.gov)

- ^ National Security Agency (www.britannica.com)

- ^ were established (www.govinfo.gov)

- ^ virtually no congressional oversight (fas.org)

- ^ of this intelligence apparatus (www.intelligence.senate.gov)

- ^ presidential direction (library.cqpress.com)

- ^ activities undertaken by these agencies (2001-2009.state.gov)

- ^ CIA overthrew the democratically elected leader of Iran (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ little or no awareness that the CIA (foreignpolicy.com)

- ^ information uncovered in the Watergate hearings (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ some key investigative journalism (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ and in the U.S. (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho) (www.senate.gov)

- ^ was established (www.congress.gov)

- ^ in 1975 (www.senate.gov)

- ^ unsuccessful attempts to kill Fidel Castro (www.politico.com)

- ^ he’s similar in that he’s a civilian involved in foreign affairs (www.vox.com)

- ^ The Church Committee discovered (www.aarclibrary.org)

- ^ intelligence agencies could plot overthrowing or murdering foreign leaders (nsarchive2.gwu.edu)

- ^ flabbergasted lawmakers (constitutioncenter.org)

- ^ AP Photo/Henry Griffin (www.apimages.com)

- ^ its sister committee in the House (www.cia.gov)

- ^ House (www.cia.gov)

- ^ Senate Intelligence Committees (www.senate.gov)

- ^ kept fully and currently informed by the intelligence agencies (www.senate.gov)

- ^ imperative of congressional oversight (www.belfercenter.org)

- ^ the Iran-Contra affair (www.brown.edu)

- ^ personal political benefit for the president, as the Ukraine affair represents with Trump (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ the House formed an Iran-Contra investigating committee (archive.org)

- ^ led by Oliver North (www.pbs.org)

- ^ Richard Secord, with a military background, and Albert Hakim (www.chicagotribune.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Lana Harris (www.apimages.com)

- ^ 9/11, when al-Qaida terrorists destroyed the World Trade Center (www.britannica.com)

- ^ they had known in advance – and ignored (www.politico.com)

- ^ President Bush’s daily briefing from the intelligence community had warned (web.archive.org)

- ^ Reuters/Kevin Lamarque (pictures.reuters.com)

- ^ what many consider (www.newsweek.com)

- ^ bent the CIA’s intelligence reporting to support a United States invasion (www.npr.org)

- ^ extremely dubious tales of the informant known as “Curveball (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter (theconversation.com)

Authors: Charles Tiefer, Professor of Law, University of Baltimore