Political cartoonists are out of touch – it's time to make way for memes

- Written by Jennifer Grygiel, Assistant Professor of Communications (Social Media) & Magazine, News and Digital Journalism, Syracuse University

The New York Times came under fire[1] after a political cartoon appeared in print on April 25, 2019. In it, a blind President Donald Trump, wearing sunglasses and a yarmulke, leads, with a leash, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who’s depicted as a dog with a Star of David around his neck.

The Times later issued an apology[2], called the cartoon “anti-Semitic,” and announced that it would discipline the editor and enhance its bias training. The newspaper also indicated that it will no longer use[3] the syndication service that supplied the cartoon.

To some, this might appear to be a significant move. But it fails to address larger problems with editorial cartooning – namely, the ranks of cartoonists are too white, too old and too male.

As a scholar who studies social media and memetics[4], I wonder if political cartoons are the best way to connect with today’s diverse readership. Many crave searing, cutting political commentary – and they’re finding it in internet memes.

What if internet memes were elevated – not only as a serious art form but also as an important form of editorializing that’s worthy of appearing alongside the traditional cartoon?

Behind the times

Newspapers and magazine editors still rely on political cartoons[5] to capture readers’ attention and to deliver some lighter material alongside heavier news stories. The need for this content isn’t going away, nor is the need for forms of communication that challenge governments and open up important public discussions[6] – a role the political cartoonist has long held.

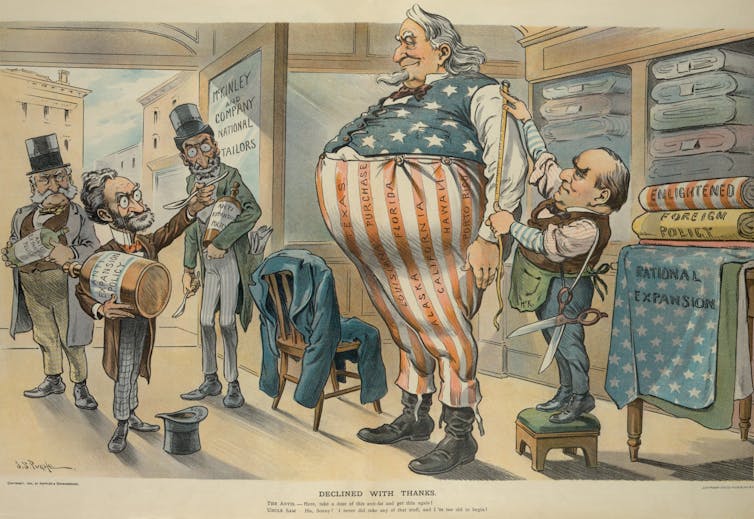

Political cartoons have long been used to criticize – and mock – those in power.

Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com[7]

Political cartoons have long been used to criticize – and mock – those in power.

Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com[7]

But in many ways, political cartooning can seem like a relic of a bygone era.

A 2015 Washington Post report also underscored the lack of diversity among political cartoonists in newsrooms[8], noting how not a single black individual was employed as one.

Then there’s journalism’s top prize, the Pulitzer.

An extensive 2016 study by the Columbia Journalism Review[9] unveiled how the ranks of editorial cartoon Pulitzer winners have been largely dominated by white men. Since 1922, only two women have received a Pulitzer in this category, and it wasn’t awarded to an African American until this year, when syndicated cartoonist Darrin Bell became the first to receive the award[10].

One roadblock to diversifying the ranks of political cartoonists is that the potential pool of candidates is limited. Few have the technical skill to draw pen-and-ink drollery, the common style for political cartooning.

Another has to do with industry trends. A 2017 study found that many newspapers don’t even employ an editorial cartoonist anymore[11]. Instead, they’ve come to rely on less expensive syndication services.

A more democratic form

Given the important function of the political cartoon, simply discontinuing their use serves no one, including publishers.

But the field’s high barrier to entry – not to mention the time it takes to actually produce a cartoon – clearly poses a problem. A new, quicker and more inclusive solution to political commentary is needed.

The political cartoon is technically a meme[12], which is simply any piece of culture that can be copied or replicated.

A different sort of political cartoon, the internet meme, dominates on social media. Often crudely constructed, they’re far easier to create than, say, your typical New Yorker political cartoon. Many simply appear as a photo with text overlay, something that can be made within a few minutes via an online meme generator or mobile app. But the lack of technical skill needed means that they’re democratic in nature – and those that resonate the best will get shared the most and rise to the top.

A new common meme format simply entails brief, humorous, text-based commentary. Words are memes, after all, and they can be used to communicate ideas very quickly and clearly, which avoids some of the issues with visual rhetoric such as misinterpretation or misrepresentation – the exact sort of thing that happened with The New York Times cartoon.

Memers of the world, unite!

Cartooning is undoubtedly a skilled art form. But in 2019, an ugly internet meme that uses a screen grab from “The Office” and quippy text overlay can have just as much clout – if not more – than a sophisticated political cartoon.

Internet memes increasingly play a role in politics and even have the power to influence elections[13]. Facebook groups with hundreds of thousands of followers are dedicated entirely to propagating and spreading political internet memes, such as the Bernie Sanders Dank Meme Stash[14] and God Emperor Trump[15].

Politics has become, in many ways – as campaign strategist Doyle Canning put it – “a battle of the memes[16].”

Some publishers and media outlets understand the value of user-generated content in political discourse and news gathering. For example, BuzzFeed[17] occasionally posts lighthearted political internet memes on its social media platforms that speak to a younger audience. The Associated Press employs user-generated content editors[18] who comb social media platforms for important images associated with news events.

Memers, meanwhile, are beginning to see their role in driving internet traffic – and ad revenue – and are beginning to formalize their work and employment as content creators. They’re even beginning to organize, with some groups seeking union status[19]. It’s possible that new syndication services may develop for political memes out of these efforts.

But there have been few signs of anyone printing a meme in a physical newspaper or magazine unless it’s controversial enough to become the topic of a news story. To serve print needs, what if publishers hired staff memers or freelance memers – individuals with a pulse for viral content and an understanding of what resonates with younger readers, who could construct stylized, more professional-looking memes that could appear in print and on the web?

Again, this isn’t to say that traditional political cartoons no longer have a role. But it’s time for publishers to anoint the internet meme as worthy of publication.

After all, the best political commentary is just as likely to be found on Tumblr as the pages of the Times.

References

- ^ under fire (www.cnn.com)

- ^ issued an apology (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ it will no longer use (www.thedailybeast.com)

- ^ As a scholar who studies social media and memetics (newhouse.syr.edu)

- ^ still rely on political cartoons (link.springer.com)

- ^ challenge governments and open up important public discussions (www-tandfonline-com.libezproxy2.syr.edu)

- ^ Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com (www.shutterstock.com)

- ^ lack of diversity among political cartoonists in newsrooms (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ 2016 study by the Columbia Journalism Review (www.cjr.org)

- ^ first to receive the award (www.npr.org)

- ^ many newspapers don’t even employ an editorial cartoonist anymore (www-tandfonline-com.libezproxy2.syr.edu)

- ^ meme (www.merriam-webster.com)

- ^ influence elections (www.wired.com)

- ^ Bernie Sanders Dank Meme Stash (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ God Emperor Trump (www.facebook.com)

- ^ a battle of the memes (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ BuzzFeed (www.instagram.com)

- ^ user-generated content editors (www.poynter.org)

- ^ seeking union status (www.vox.com)

Authors: Jennifer Grygiel, Assistant Professor of Communications (Social Media) & Magazine, News and Digital Journalism, Syracuse University