Beyond blackface: How college yearbooks captured protest and change

- Written by John R. Thelin, University Research Professor, University of Kentucky

Ever since a photograph surfaced of someone in blackface – and another dressed in a Ku Klux Klan robe – on the medical college yearbook page[1] of Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam in February, efforts to scour college yearbooks have focused on finding similarly racist imagery.

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam speaks at a news conference after revelations that his medical school yearbook page features photos of a man in blackface.

Steve Helber/AP[2]

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam speaks at a news conference after revelations that his medical school yearbook page features photos of a man in blackface.

Steve Helber/AP[2]

USA Today, for instance, sent 78 reporters[3] to page through more than 900 college yearbooks from the 1970s and ‘80s. The newspaper not only discovered photographs of students dressed in KKK robes and blackface, but also at mock lynchings and other blatant “displays of racism[4].”

This focus on the racist reveling of college graduates from yesteryear who are today’s power elite is justified. However, as one who has studied college yearbooks[5] – and who has written a book about going to college in the sixties[6] – I believe this narrow focus on racist imagery obscures a similarly important element of college yearbooks that began to appear during a critical turning point for higher education in the United States.

Black representation

One of my biggest concerns with the current focus on racist imagery in college yearbooks is that in the search for images of blackface, journalists and others are overlooking the importance of the faces of black students. Black representation is important to consider because it wasn’t until the latter half of the 20th century that many of America’s colleges and universities began to accept black students.

Because of the topic of my book, I’ve mostly studied yearbooks from the 1960s – some 20 years before Northam graduated from medical school. During this time period, in the Southeastern Conference[7] – where a Confederate legacy still loomed[8] – the first African-American student on a varsity basketball team was Perry Wallace of Vanderbilt during the 1967-68 season when he was a sophomore. Wallace appears on five different pages of the 1969 edition of The Vanderbilt Commodore, the college yearbook at Vanderbilt University. Perry majored in electrical engineering. He graduated from Columbia Law School and went on to become a distinguished law professor at George Washington University.

Vanderbilt’s Perry Wallace (25) scoops the rebound down from the Kentucky basket, in 1968, in Lexington, Kentucky.

H.B. Littell/AP[9]

Vanderbilt’s Perry Wallace (25) scoops the rebound down from the Kentucky basket, in 1968, in Lexington, Kentucky.

H.B. Littell/AP[9]

The 1968 and 1969 editions of The Kentuckian – the college yearbook at the University of Kentucky where I teach – are also interesting case studies.

The University of Kentucky is home of the first African-Americans to play football in the Southeastern Conference: Greg Page[10] and Nate Northington[11], later joined by Wilbur Hackett[12] and Houston Hogg[13]. The 1968 edition of the university’s yearbook – The Kentuckian – focused on a team tragedy[14] – Page’s death. “Page had lain paralyzed for over a month due to an injury suffered in preseason practice,” an entry in the yearbook states. “But as it had to be, football continued.”

The appearance of black students in college yearbooks during this time period serves as a historical reminder that even though many colleges had become racially desegregated earlier, campus activities were still often racially exclusive. Black students were first admitted to the University of Kentucky in 1949 but were not allowed to participate in many student activities until much later – 1967[15] in the case of varsity sports. That’s a long delay. It indicates that admission did not necessarily mean full citizenship within the campus community.

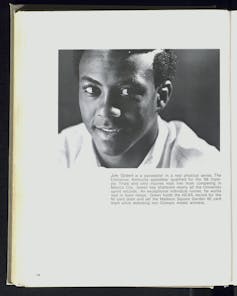

Jim Green, the first African-American track and field athlete at the University of Kentucky, who went on to win NCAA championships, was honored in the 1969 Kentuckian as one of the university’s ‘Pacesetters’ for outstanding contributions in 1968-1969.

The Kentuckian[16]

Jim Green, the first African-American track and field athlete at the University of Kentucky, who went on to win NCAA championships, was honored in the 1969 Kentuckian as one of the university’s ‘Pacesetters’ for outstanding contributions in 1968-1969.

The Kentuckian[16]

An era of protest

My other concern about the focus on racist imagery is that it distracts from the fact that, particularly during the late 1960s, college yearbooks helped chronicle an era of student protest and campus activism. Sometimes, college yearbook editors deliberately put images of traditional campus events alongside images of demonstrations and protests.

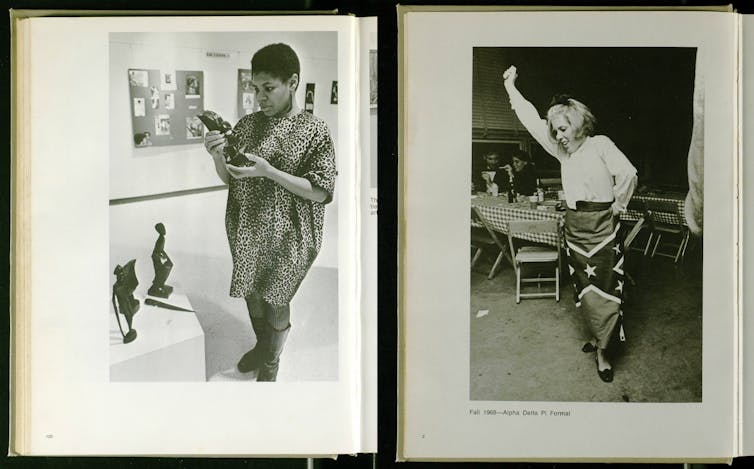

That’s what Gretchen Marcum Brown, editor of The Kentuckian had in mind during her stint as editor for the 1969 edition, which is particularly noteworthy for the amount of material that reflects black culture and politics. For instance, the 1969 yearbook features speakers such as civil rights activist Julian Bond, The Supremes, and extended photo caption information about a black history course and the Black Student Union. In a recent interview for this article, Brown told me she wanted to document the intense political events taking place on and off campus during the 1968-69 academic year.

In her acknowledgments, Brown credited the influence of Sam Abell, her predecessor who went on to become a renowned photographer for National Geographic[17]. Abell had advised Brown to start the 1969 yearbook with a photo essay in which traditional campus events, such as a Greek life prom in which students were dressed in Confederate regalia, would be placed alongside or near images of student groups seeking to uproot the status quo.

A student shown in a 1969 University of Kentucky yearbook examines African art in one photograph, while in another photograph in the same book, a student dances while draped in a Confederate flag.

The Kentuckian, 1968-69[18]

A student shown in a 1969 University of Kentucky yearbook examines African art in one photograph, while in another photograph in the same book, a student dances while draped in a Confederate flag.

The Kentuckian, 1968-69[18]

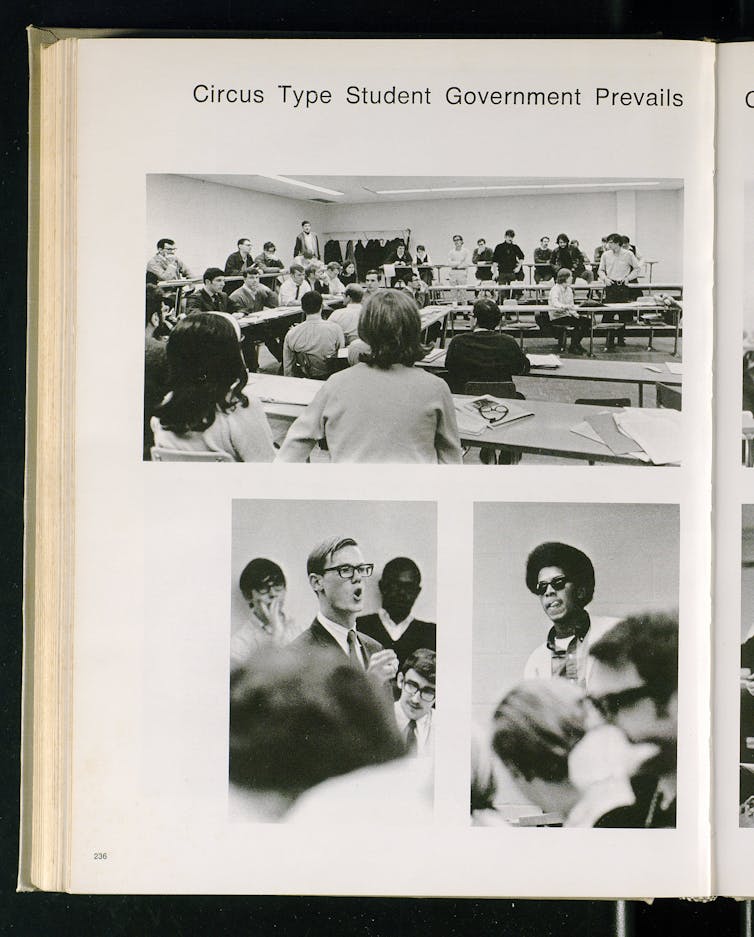

The yearbook included extended coverage of controversies within student government. This included the house speaker of the student government telling the 40 black students present to “protest his bill requesting that 'Dixie’ be played at athletic events, that the song was not racist.”

A student government house speaker challenges black students to protest a bill he brought forth to have ‘Dixie’ sung before sporting events.

The Kentuckian, 1969[19]

A student government house speaker challenges black students to protest a bill he brought forth to have ‘Dixie’ sung before sporting events.

The Kentuckian, 1969[19]

Imagining a better future

At the end of a lengthy section on Greek life, the yearbook editor quoted fraternity leaders who invoked the importance of “brotherhood.” But she didn’t just let the brotherhood claim go unchecked. Instead, Brown broached the sensitive issue of racial exclusion. “Brotherhood is cheering together at a football game. Brotherhood is hanging together when the going gets tough. Brotherhood is borrowing your roommates’ clothes. Brotherhood may or may not be a ‘Caucasian only’ clause in your constitution.”

This wry observation showed awareness of both inclusion and exclusion in campus life.

The yearbook concluded with a photograph of a campus demonstration in which a student holds a placard that asked the University of Kentucky campus, “Will You Grow Up?” The editor’s final comment was, “This book is dedicated to those who have the courage and foresight for true reappraisal.”

The Kentuckian was not unique in its attention to social change. A review of yearbooks from Louisiana State University, North Carolina State University and the University of Mississippi shows a similar emphasis on student awareness of the political climate at the time, balanced by coverage of traditional campus life activities.

Yearbook editors challenged readers to reconsider what college education was about and what a university should be. For example, the 1969 Agromeck yearbook[20] of North Carolina State University, stated: “N.C. State’s heritage is essentially like that of any other predominantly white, southern technically oriented institution. The virtues which the school extols are Discipline, Patriotism, Hard Work and Good Grades.”

However, the yearbook editor continued: “There are changes afoot. From the past comes a dual tradition of technical and liberal education and the factors have clashed openly in the present.” Its major photographic essay presented themes of conflict and change within the university.

College yearbooks were built to last. They were also meant to commemorate the worlds that students created. This means that in 2019 alumni, and now the public, can look back at the blackface parties of 1984, the year of Gov. Northam’s medical college yearbook – but also at the student protests of 1969.

References

- ^ medical college yearbook page (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Steve Helber/AP (www.apimages.com)

- ^ sent 78 reporters (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ displays of racism (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ studied college yearbooks (www.insidehighered.com)

- ^ going to college in the sixties (jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu)

- ^ Southeastern Conference (www.secsports.com)

- ^ Confederate legacy still loomed (ussporthistory.com)

- ^ H.B. Littell/AP (www.apimages.com)

- ^ Greg Page (www.wymt.com)

- ^ Nate Northington (theundefeated.com)

- ^ Wilbur Hackett (ukathletics.com)

- ^ Houston Hogg (www.owensboroliving.com)

- ^ tragedy (www.wymt.com)

- ^ 1967 (www.kentucky.com)

- ^ The Kentuckian (exploreuk.uky.edu)

- ^ renowned photographer for National Geographic (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ The Kentuckian, 1968-69 (exploreuk.uky.edu)

- ^ The Kentuckian, 1969 (exploreuk.uky.edu)

- ^ 1969 Agromeck yearbook (d.lib.ncsu.edu)

Authors: John R. Thelin, University Research Professor, University of Kentucky

Read more http://theconversation.com/beyond-blackface-how-college-yearbooks-captured-protest-and-change-111419