University of California's break with the biggest academic publisher could shake up scholarly publishing for good

- Written by MacKenzie Smith, University Librarian and Vice Provost for Digital Scholarship, University of California, Davis

The University of California recently made international headlines when it canceled its subscription[1] with scientific journal publisher Elsevier[2]. The twittersphere lit up[3]. And Elsevier’s parent company, RELX, saw its stock drop 7 percent[4] in response to the announcement.

A library canceling a subscription seems like a simple, everyday business decision, so what’s the big deal?

It was not just the clash-of-the-titans drama between the University of California, whose scholars produce nearly 10 percent[5] of the nation’s research publications, and Elsevier, the world’s largest publisher[6] of academic research.

The story made headlines because it’s symptomatic of the way in which the internet has failed to deliver on the promise to make knowledge easily accessible and shareable by anyone, anywhere in the world. The UC-Elsevier showdown was the latest in a succession of cracks in what is widely considered to be a failing system[7] for sharing academic research. As the head of the research library at UC Davis[8], I see this development as a harbinger of a tectonic shift in how universities and their faculty share research, build reputations and preserve knowledge in the digital age.

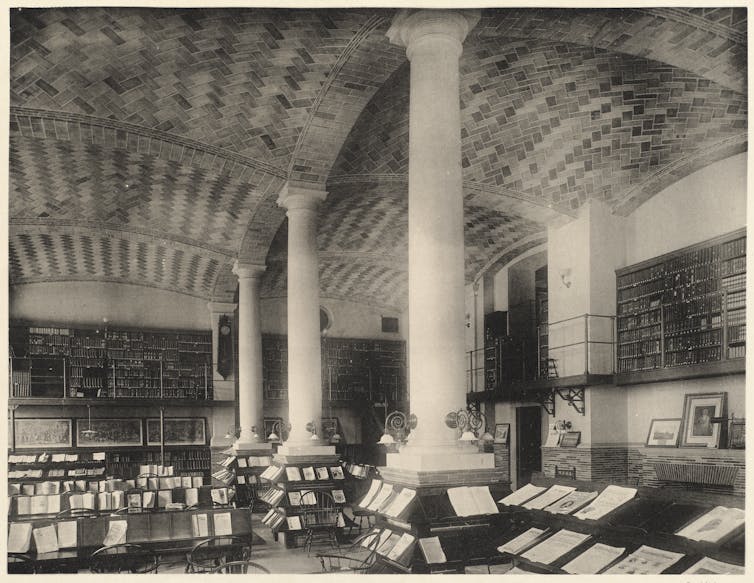

Accessing a journal no longer means going to a periodicals room.

Newton W. Elwell/Boston Public Library/Flickr, CC BY[9][10]

Accessing a journal no longer means going to a periodicals room.

Newton W. Elwell/Boston Public Library/Flickr, CC BY[9][10]

Moving from stacks to screens

Here’s how things traditionally worked.

Universities have always subscribed to scientific journals so their researchers can study and build on the work that came before, and won’t needlessly duplicate research they never knew about. In the print age, university library shelves were lined with journals, available for any researcher or – in the case of public universities like the University of California – any member of the public to peruse and learn from.

Now, for almost all journals, and a growing number of books, libraries sign contracts to license access to digital versions. Since academic publishers moved their journals online, it has become rare for libraries to subscribe to printed journals, and researchers have adapted to the convenience of accessing journal articles on the internet.

Under the new business model of licensing access to journals online rather than distributing them in print, for-profit publishers often lock libraries into bundled subscriptions that wrap the majority of a publisher’s portfolio of journals – almost 3,000 in Elsevier’s case[11] – into a single, multi-million dollar package. Rather than storing back issues on shelves, libraries can lose permanent access to journals when a contract expires. And members of the public can no longer read the library’s copy of a journal because the licenses are limited to members of the university. Now the public must buy online copies of academic articles for an average of US$35 to $40 a pop.

The shift to digital has been good for researchers in many ways. It is far more convenient to search for articles online, and easier to access and download a copy – provided you work for an institution with a paid subscription. Modern software makes organizing and annotating them simpler, too. With all of these benefits, no one would advocate for going back to the old days of print journals.

But this online system did not improve the picture overall. Despite digital copies of articles costing nothing to duplicate and the cost of producing an article online being lower than in the past, the cost to libraries of licensing access to them has continued to experience hyperinflation[12]. No library[13] can afford to license all of the journals that its faculty and students want access to, and many researchers around the world are shut out completely. Compounding the problem, consolidation in the scholarly publishing market[14] has reduced competition significantly, causing even more price inflexibility.

Excessive profits?

Academic publishers certainly bear costs. They pay for professional editors and programmers, they manage the peer review process, they market their journals and so on. However, their revenues far exceed these costs and are among the highest of any companies in the world. Elsevier’s profit margin is reported to be nearly 40 percent[15] far higher than even Apple at around 23 percent[16].

Where social media platforms like Facebook profit from – and indeed, would not exist without – the content generated by users, the parallel is true[17] for academic journals. Companies like Elsevier receive articles from university faculty and other researchers for free, summarizing research that was often publicly funded by government grants. Then other faculty and researchers serve on their editorial boards and peer-review those articles for free or a nominal fee. Finally the company publishes them in journals available only behind a paywall.

And there’s the rub: the paywall. The great promise of the internet was that it would make knowledge more freely and easily accessible[18]. In the world of academic research – where new discoveries are made and new knowledge is born – the hope 20 years ago was that the advent of online platforms would make research articles universally available. It would also bring down the cost of publishing scholarly journals and, consequently, begin to reduce the multi-million dollar subscription costs borne by universities and other research institutions.

Instead, articles are not readily available to everyone, subscription costs have continued to rise, and subscribers’ rights have eroded, including what they can do with articles they buy and their ability to provide long-term access to them.

What happened to sharing knowledge with the people who need it, funded or created it?

A model for the digital age

Maybe it’s time to just blow up the whole system and start over. But the system of sharing knowledge that scholars have today evolved over hundreds of years and contains certain qualities – peer review of accuracy, editorial judgment, long-term preservation – still matter deeply.

While research products – books, journals and articles – would definitely benefit from modernization in the digital age, we at the University of California are focusing on fixing the business model first. Paywalls and online subscriptions may make sense in other parts of the media ecosystem, but it’s not a good model for academic publishing, where authors and reviewers are paid by universities and research grants (with public money) rather than by publishers.

The open access movement would get rid of paywalls and let anyone read anything for free.

Inked Pixels/Shutterstock.com[19]

The open access movement would get rid of paywalls and let anyone read anything for free.

Inked Pixels/Shutterstock.com[19]

Fortunately, the academy has another option for a publishing business model that can better achieve the promise of the internet: open access. In that model, authors, or their funders or institutions, pay the publisher a fee to cover the cost of publishing each article. In exchange, the articles are made freely available for everyone to read online, anywhere, anytime. Article quality is preserved by the same unpaid peer-review system. Libraries at research institutions could shift their payments from licenses and subscriptions to publication fees for their affiliated authors. The cost is theoretically the same, but everyone can read everything for free.

The University of California has long supported the ideals of open access[20] – allowing everyone in the world to access the knowledge created by its faculty and researchers, for the benefit of all. In fact, since open access became an option for publishing, more and more UC authors, following the global trend[21], have independently chosen to pay their publisher a fee in order to make their article freely available to the public.

But those fees come on top of the tens of millions of dollars[22] that the university is already paying the publisher for access to the same articles. This “double dipping[23]” by publishers was the final straw in UC’s resolve to change the system.

Several years ago, I worked[24] with colleagues within the University of California and other academic research institutions to study the costs of publishing with this open access model[25]. We found that, while costs would shift and more research-grant funds may need to be applied to publishing fees, overall it would be affordable[26] for research universities, at least in North America where libraries are relatively well funded. With these results, UC could see a way out of its dilemma.

When UC’s contract with Elsevier was up for renewal, we resolved to put our ideas into practice and pursue the twin goals of increasing open access to UC’s research while containing or lowering our journal-related costs – and finally achieving something of the promise of the internet. While I was not on UC’s negotiating team, I was among the group of faculty and library leaders that worked closely with them and decided to take this step.

Our goals are ambitious and their implementation will be complex. Changing a system this intricate is akin to modernizing the FAA’s air traffic control system – a million planes are in the air at any moment and changing anything can have serious consequences elsewhere. But we have to start somewhere or the whole system is at risk, and UC has placed its bet. We join a global movement[27] that began in Europe and is expanding around the world, and we believe we’re now on the path to a better system for sharing knowledge in the 21st century.

References

- ^ canceled its subscription (www.universityofcalifornia.edu)

- ^ Elsevier (www.elsevier.com)

- ^ lit up (twitter.com)

- ^ drop 7 percent (uk.reuters.com)

- ^ produce nearly 10 percent (accountability.universityofcalifornia.edu)

- ^ world’s largest publisher (www.latimes.com)

- ^ failing system (www.researchinformation.info)

- ^ As the head of the research library at UC Davis (leadership.ucdavis.edu)

- ^ Newton W. Elwell/Boston Public Library/Flickr (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ almost 3,000 in Elsevier’s case (www.elsevier.com)

- ^ hyperinflation (www.arl.org)

- ^ No library (theconversation.com)

- ^ consolidation in the scholarly publishing market (doi.org)

- ^ nearly 40 percent (www.forbes.com)

- ^ around 23 percent (www.macrotrends.net)

- ^ the parallel is true (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ knowledge more freely and easily accessible (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Inked Pixels/Shutterstock.com (www.shutterstock.com)

- ^ supported the ideals of open access (osc.universityofcalifornia.edu)

- ^ global trend (doi.org)

- ^ tens of millions of dollars (www.universityofcalifornia.edu)

- ^ double dipping (www.wsj.com)

- ^ I worked (scholar.google.com)

- ^ costs of publishing with this open access model (www.library.ucdavis.edu)

- ^ overall it would be affordable (dx.doi.org)

- ^ global movement (oa2020.org)

Authors: MacKenzie Smith, University Librarian and Vice Provost for Digital Scholarship, University of California, Davis