Regenerative agriculture can make farmers stewards of the land again

- Written by Stephanie Anderson, Instructor of English, Florida Atlantic University

For years, “sustainable” has been the buzzword in conversations about agriculture. If farmers and ranchers could slow or stop further damage to land and water, the thinking went, that was good enough. I thought that way too, until I started writing my new book, “One Size Fits None: A Farm Girl’s Search for the Promise of Regenerative Agriculture[1].”

I grew up on a cattle ranch in western South Dakota and once worked as an agricultural journalist. For me, agriculture is more than a topic – it is who I am. When I began working on my book, I thought I would be writing about sustainability as a response to the environmental damage caused by conventional agriculture – farming that is industrial and heavily reliant on oil and agrochemicals[2], such as pesticides and fertilizers.

But through research and interviews with farmers and ranchers around the United States, I discovered that sustainability’s “give back what you take” approach, which usually just maintains or marginally improves resources already degraded by generations of conventional agriculture, does not adequately address the biggest long-term challenge farmers face: climate change.

But there is an alternative. A method called regenerative agriculture[3] promises to create new resources, restoring them to preindustrial levels or better. This is good for farmers as well as the environment, since it lets them reduce their use of agrochemicals while making their land more productive.

North Dakota farmer Gabe Brown describes how regenerative methods have improved soil on his farm.What holds conventional farmers back

Modern American food production remains predominantly conventional. Growing up in a rural community of farmers and ranchers, I saw firsthand why.

As food markets globalized in the early 1900s, farmers began specializing in select commodity crops and animals to increase profits. But specialization made farms less resilient: If a key crop failed or prices tumbled, they had no other income source. Most farmers stopped growing their own food, which made them dependent on agribusiness retailers.

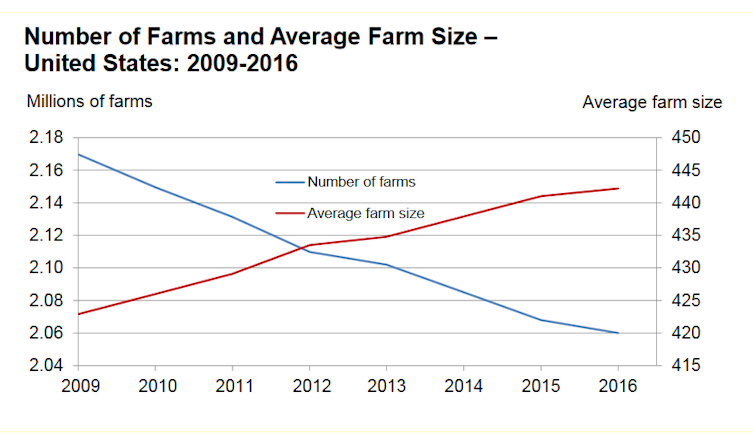

Under these conditions small farms consolidated into large ones as families went bankrupt – a trend that continues today[4]. At the same time, agribusiness companies began marketing new machines and agrochemicals. Farmers embraced these tools, seeking to stay in business, specialize further and increase production.

In the 1970s, the government’s position became “Get big or get out[5]” under Earl Butz, who served as Secretary of Agriculture from 1971 to 1976. In the years since, critics like the nonprofit Food and Water Watch[6] have raised concerns that corporate representatives have dictated land grant university research[7] by obtaining leadership positions, funding agribusiness-friendly studies, and silencing scientists whose results conflict with industrial principles.

University of Nebraska – Lincoln, data from USDA, CC BY-ND[8][9]

These companies have also shaped government policies in their favor, as economist Robert Albritton describes in his book “Let Them Eat Junk[10].” These actions encouraged the growth of large industrialized farms that rely on genetically modified seeds[11], agrochemicals and fossil fuel.

Several generations into this system, many conventional farmers feel trapped. They lack the knowledge required to farm without inputs, their farms are big and highly specialized, and most are carrying operating loans and other debts.

In contrast, regenerative agriculture releases farmers from dependence on agribusiness products. For example, instead of purchasing synthetic fertilizers for soil fertility, producers rely on diverse crop rotations, no-till planting and management of livestock grazing impacts.

Agribusiness dogma[12] says that regenerative agriculture cannot feed the world and or ensure a healthy bottom line for farmers, even as conventional farmers are going bankrupt[13]. I have heard this view from people I grew up with in South Dakota and interviewed as a farm journalist.

“Everybody seems to want smaller local producers,” Ryan Roth, a farmer from Belle Glade, Florida told me. “But they can’t keep up. It’s unfortunate. I think it’s not the best development for agriculture operations to get bigger, but it is what we’re dealing with.”

The climate threat

Climate change is making it increasingly hard for farmers to keep thinking this way. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that without rapid action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over roughly the next decade, warming will trigger devastating impacts[14] such as wildfires, droughts, floods and food shortages.

For farmers, large-scale climate change will cause[15] decreased crop yields and quality, heat stress for livestock, disease and pest outbreaks, desertification on rangelands, changes in water availability and soil erosion.

University of Nebraska – Lincoln, data from USDA, CC BY-ND[8][9]

These companies have also shaped government policies in their favor, as economist Robert Albritton describes in his book “Let Them Eat Junk[10].” These actions encouraged the growth of large industrialized farms that rely on genetically modified seeds[11], agrochemicals and fossil fuel.

Several generations into this system, many conventional farmers feel trapped. They lack the knowledge required to farm without inputs, their farms are big and highly specialized, and most are carrying operating loans and other debts.

In contrast, regenerative agriculture releases farmers from dependence on agribusiness products. For example, instead of purchasing synthetic fertilizers for soil fertility, producers rely on diverse crop rotations, no-till planting and management of livestock grazing impacts.

Agribusiness dogma[12] says that regenerative agriculture cannot feed the world and or ensure a healthy bottom line for farmers, even as conventional farmers are going bankrupt[13]. I have heard this view from people I grew up with in South Dakota and interviewed as a farm journalist.

“Everybody seems to want smaller local producers,” Ryan Roth, a farmer from Belle Glade, Florida told me. “But they can’t keep up. It’s unfortunate. I think it’s not the best development for agriculture operations to get bigger, but it is what we’re dealing with.”

The climate threat

Climate change is making it increasingly hard for farmers to keep thinking this way. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that without rapid action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over roughly the next decade, warming will trigger devastating impacts[14] such as wildfires, droughts, floods and food shortages.

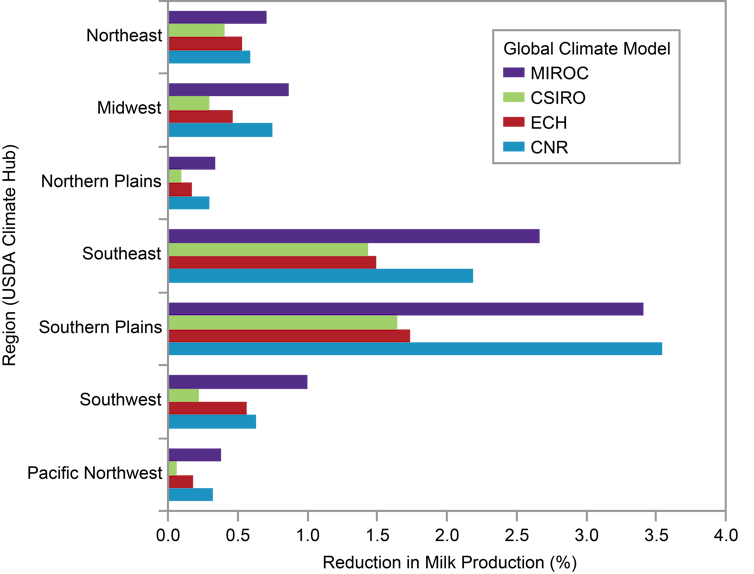

For farmers, large-scale climate change will cause[15] decreased crop yields and quality, heat stress for livestock, disease and pest outbreaks, desertification on rangelands, changes in water availability and soil erosion.

Projected milk production losses through 2030 due to heat stress in dairy cattle.

USGCRP[16]

As I explain in my book, regenerative agriculture is an effective response to climate change because producers do not use agrochemicals – many of which are derived from fossil fuels – and greatly reduce their reliance on oil. The experiences of farmers who have adopted regenerative agriculture show that it restores soil carbon[17], literally locking carbon up underground, while also reversing desertification, recharging water systems[18], increasing biodiversity and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And it produces nutrient-rich food and promises to enliven rural communities and reduce corporate control of the food system.

No single model

How farmers put this strategy into practice differs depending on their location, goals and community needs. Regenerative agriculture is a one-size-fits-none model of farming that allows for flexibility and close tailoring to individual environments.

At Great Plains Buffalo[19] in South Dakota, for example, rancher Phil Jerde is reversing desertification[20] on the grassland. Phil moves buffalo across the land in a way that mimics their historic movement over the Great Plains, rotating them frequently through small pastures so they stay bunched together and impact the land evenly via their trampling and waste distribution. The land has adequate time to rest and regrow between rotations.

After transitioning his conventional ranch to a regenerative one over 10 years, Phil saw bare ground revert back to prairie grassland. Water infiltration into the ground increased, his herd’s health improved, wildlife and insect populations recovered and native grasses reappeared.

On Brown’s Ranch[21] in North Dakota, farmer Gabe Brown also converted his conventional operation to a regenerative one in a decade. He used a combination of cover crops, multicropping (growing two or more crops on a piece of land in a single season), intercropping (growing two or more crops together), an intensive rotational grazing system called mob grazing, and no-till farming[22] to restore soil organic matter levels to just over 6 percent – roughly the level most native prairie soils contained before settlers plowed them up[23]. Restoring organic matter sequesters carbon in the soil, helping to slow climate change.

Conventional farmers often worry about losing the illusion of control that agrochemicals, monocultures and genetically modified seeds provide. I asked Gabe how he overcame these fears. He replied that one of the most important lessons was learning to embrace the environment instead of fighting it.

“Regenerative agriculture can be done anywhere because the principles are the same,” he said. “I always hear, ‘We don’t get the moisture or this or that.’ The principles are the same everywhere. There’s nature everywhere. You’re just mimicking nature is all you’re doing.”

The future

Researchers with Project Drawdown[24], a nonprofit that spotlights substantive responses to climate change, estimate that land devoted to regenerative agriculture worldwide will increase from 108 million acres currently to 1 billion acres by 2050[25]. More resources are appearing to help farmers make the transition, such as investment groups[26], university programs[27] and farmer-to-farmer training networks[28].

Organic food sales continue to rise[29], suggesting that consumers want responsibly grown food. Even big food companies like General Mills[30] are embracing regenerative agriculture.

The question now is whether more of America’s farmers and ranchers will do the same.

Projected milk production losses through 2030 due to heat stress in dairy cattle.

USGCRP[16]

As I explain in my book, regenerative agriculture is an effective response to climate change because producers do not use agrochemicals – many of which are derived from fossil fuels – and greatly reduce their reliance on oil. The experiences of farmers who have adopted regenerative agriculture show that it restores soil carbon[17], literally locking carbon up underground, while also reversing desertification, recharging water systems[18], increasing biodiversity and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And it produces nutrient-rich food and promises to enliven rural communities and reduce corporate control of the food system.

No single model

How farmers put this strategy into practice differs depending on their location, goals and community needs. Regenerative agriculture is a one-size-fits-none model of farming that allows for flexibility and close tailoring to individual environments.

At Great Plains Buffalo[19] in South Dakota, for example, rancher Phil Jerde is reversing desertification[20] on the grassland. Phil moves buffalo across the land in a way that mimics their historic movement over the Great Plains, rotating them frequently through small pastures so they stay bunched together and impact the land evenly via their trampling and waste distribution. The land has adequate time to rest and regrow between rotations.

After transitioning his conventional ranch to a regenerative one over 10 years, Phil saw bare ground revert back to prairie grassland. Water infiltration into the ground increased, his herd’s health improved, wildlife and insect populations recovered and native grasses reappeared.

On Brown’s Ranch[21] in North Dakota, farmer Gabe Brown also converted his conventional operation to a regenerative one in a decade. He used a combination of cover crops, multicropping (growing two or more crops on a piece of land in a single season), intercropping (growing two or more crops together), an intensive rotational grazing system called mob grazing, and no-till farming[22] to restore soil organic matter levels to just over 6 percent – roughly the level most native prairie soils contained before settlers plowed them up[23]. Restoring organic matter sequesters carbon in the soil, helping to slow climate change.

Conventional farmers often worry about losing the illusion of control that agrochemicals, monocultures and genetically modified seeds provide. I asked Gabe how he overcame these fears. He replied that one of the most important lessons was learning to embrace the environment instead of fighting it.

“Regenerative agriculture can be done anywhere because the principles are the same,” he said. “I always hear, ‘We don’t get the moisture or this or that.’ The principles are the same everywhere. There’s nature everywhere. You’re just mimicking nature is all you’re doing.”

The future

Researchers with Project Drawdown[24], a nonprofit that spotlights substantive responses to climate change, estimate that land devoted to regenerative agriculture worldwide will increase from 108 million acres currently to 1 billion acres by 2050[25]. More resources are appearing to help farmers make the transition, such as investment groups[26], university programs[27] and farmer-to-farmer training networks[28].

Organic food sales continue to rise[29], suggesting that consumers want responsibly grown food. Even big food companies like General Mills[30] are embracing regenerative agriculture.

The question now is whether more of America’s farmers and ranchers will do the same.

References

- ^ One Size Fits None: A Farm Girl’s Search for the Promise of Regenerative Agriculture (www.nebraskapress.unl.edu)

- ^ agrochemicals (www.britannica.com)

- ^ regenerative agriculture (regenerationinternational.org)

- ^ continues today (www.minneapolisfed.org)

- ^ Get big or get out (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Food and Water Watch (www.foodandwaterwatch.org)

- ^ dictated land grant university research (www.foodandwaterwatch.org)

- ^ University of Nebraska – Lincoln, data from USDA (cropwatch.unl.edu)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Let Them Eat Junk (www.plutobooks.com)

- ^ genetically modified seeds (theconversation.com)

- ^ Agribusiness dogma (www.farmprogress.com)

- ^ conventional farmers are going bankrupt (www.wsj.com)

- ^ trigger devastating impacts (www.ipcc.ch)

- ^ climate change will cause (nca2018.globalchange.gov)

- ^ USGCRP (nca2018.globalchange.gov)

- ^ restores soil carbon (www.nrcs.usda.gov)

- ^ recharging water systems (theconversation.com)

- ^ Great Plains Buffalo (www.greatplainsbuffalo.com)

- ^ desertification (www.unccd.int)

- ^ Brown’s Ranch (brownsranch.us)

- ^ no-till farming (theconversation.com)

- ^ before settlers plowed them up (www.nrcs.usda.gov)

- ^ Project Drawdown (www.drawdown.org)

- ^ 1 billion acres by 2050 (www.drawdown.org)

- ^ investment groups (www.forbes.com)

- ^ university programs (www.warren-wilson.edu)

- ^ farmer-to-farmer training networks (www.afsc.org)

- ^ continue to rise (www.ota.com)

- ^ General Mills (www.generalmills.com)

Authors: Stephanie Anderson, Instructor of English, Florida Atlantic University