In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

- Written by Thomas Robertson, Visiting Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, Macalester College

On April 9, 1940, Nazi tanks stormed into Denmark. A month later, they blitzed into Belgium, Holland and France. As Americans grew increasingly rattled by the spreading threat, a surprising place became crucial to U.S. national security[1]: the vast, ice-capped island of Greenland[2].

The island, a colony of Denmark’s at the time, was rich in mineral resources. The Nazi invasions left it and several other European colonies as international orphans.

Greenland was essential for air bases as U.S. planes flew to Europe, and also for strategic minerals[3]. Greenland’s Ivittuut (formerly Ivigtut) mine contained the world’s only reliable supply of the most important material you’ve probably never heard of: cryolite, a frosty white mineral that the U.S. and Canadian industries relied upon[4] to refine bauxite into aluminum, and thus essential to assembling a modern air force.

A month after the Nazis seized Denmark, five American Coast Guard cutters set sail[5] for Greenland, in part to protect the Ivittuut mine[6] from the Nazis.

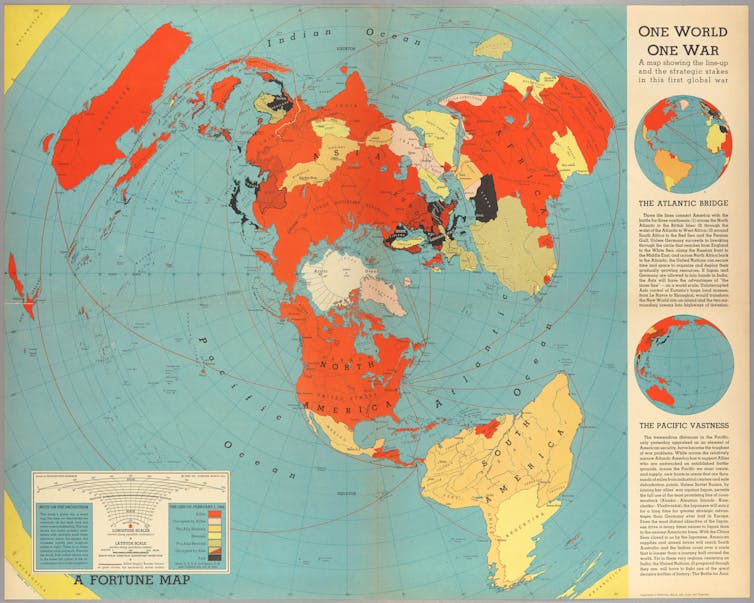

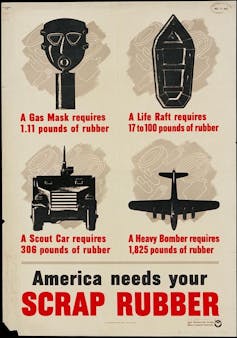

People sometimes forget that World War II was a dog-eat-dog struggle for resources – oil[8] and uranium[9] but also dozens of other materials, everything from rubber[10] to copper. Without these strategic materials, no modern military could produce crucial new weapons such as tanks and airplanes. The resource struggle often started before actual fighting.

Foreign materials fueled American global power[11], but also raised tricky questions about access to resources and about sovereignty, just as the old European imperial order was being rethought. As in 2026, U.S. presidents had to skillfully balance force and diplomacy.

As a historian[13] at Macalester College, I research how Americans shape environments around the world through their purchasing[14] and national security needs[15], and how foreign landscapes enable and constrain American actions. Today, control of Greenland’s natural resources[16] is again on an American president’s radar as demand for critical minerals[17] rises and supply tightens.

During the spring of 1940, America and its European allies mapped out patterns of resource use and ideas of global interconnection that would shape the international order for decades. Greenland helped give birth to this new order.

Rethinking American vulnerability

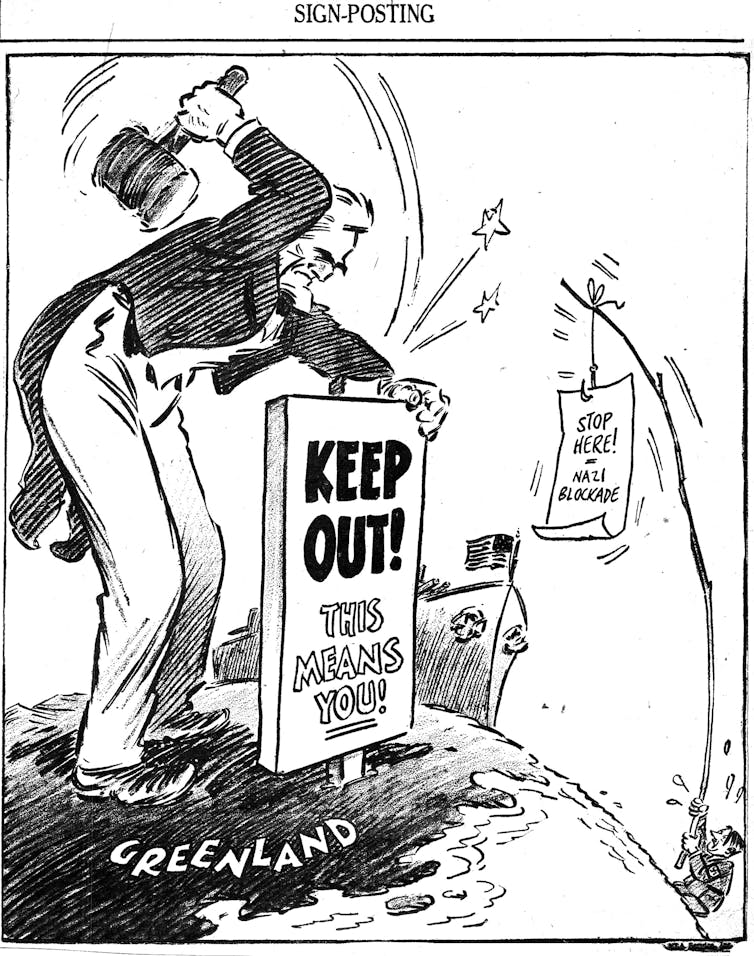

On May 16, 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress[18], including many “American first” isolationists wary of European entanglements. Roosevelt implored Americans to wake up to new threats in the world – to, in his words, “recast their thinking about national protection.”

New weapons, he warned, had shrunk the world, and oceans could no longer shield the United States. The nation’s fate was inextricably tied to Europe’s. Nothing showed this better than Greenland: “From the fiords of Greenland,” FDR warned, “it is four hours by air to Newfoundland; five hours to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and to the province of Quebec; and only six hours to New England.”

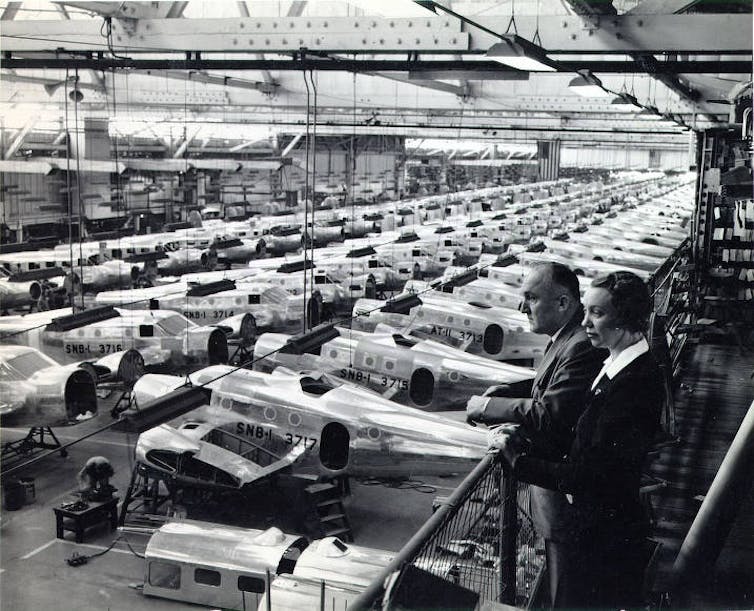

But Greenland set off alarm bells for another reason. To protect itself in a dangerous world, Roosevelt famously called for the U.S. to hammer out 50,000 planes a year[20]. But in 1938, America had produced only 1,800 planes.

To meet this ambitious goal, Roosevelt and his advisers knew that little could be done without Greenland. No Greenland, no cryolite. No cryolite, no massive American air force. Without cryolite, making 50,000 planes would be infinitely more difficult.

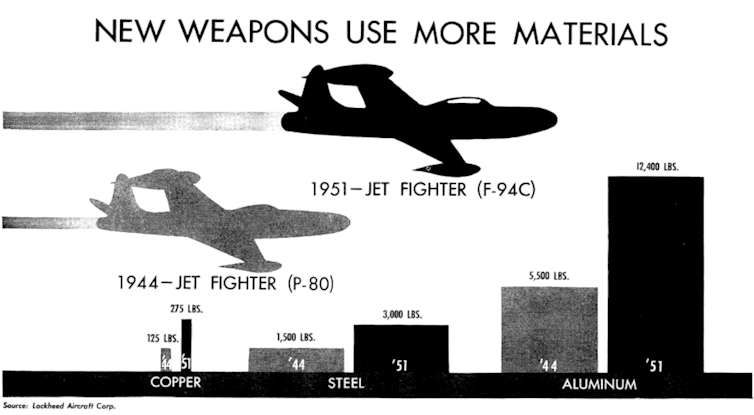

The age of alloys

Americans, National Geographic explained in 1942, lived in an “age of alloys[21].” Without aluminum alloys and other metallic mixtures, assembly lines churning out modern tanks, trucks and airplanes would grind to a halt. “More than any other struggle in history, this is a war of many metals, and the lack of a single one may be a blow far worse than the loss of a battle.”

Aluminum was crucial for modern militaries. Mechanics check an airplane engine at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, Texas, in November 1942.

Fenno Jacobs/Department of Defense[22]

Aluminum was crucial for modern militaries. Mechanics check an airplane engine at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, Texas, in November 1942.

Fenno Jacobs/Department of Defense[22]

Few materials mattered more than aluminum. Light yet strong, aluminum formed 60%[23] of a heavy bomber’s engines, 90% of its wings and fuselage, and all of its propellers.

But there was a problem: Refining aluminum from bauxite ore required working with dangerously hot metallic mixtures, over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,100 degrees Celsius)[24]. Cryolite solved the problem by reducing the temperature to a more manageable 900 F (480 C).

The Nazis’ chemical industry had found a substitute for cryolite using fluorspar[25], but the U.S. preferred the more resource-efficient cryolite and wanted to prevent the Germans from having it.

After the Nazis seized Denmark

Just days after German tanks rolled into Denmark in April 1940, Allied officials huddled[26] to devise ways to protect Ivittuut’s magical mineral. On May 3, Danish Ambassador to the U.S. Henrik de Kauffmann, risking trial for treason, requested American assistance. On May 10, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Comanche departed New England for Ivittuut. Four others[27] soon followed, one with guns for the mine’s defenders.

The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Comanche played a role in protecting Greenland mining operations starting long before the U.S. officially entered World War II.

Thomas B. MacMillan, Courtesy of Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College[28]

The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Comanche played a role in protecting Greenland mining operations starting long before the U.S. officially entered World War II.

Thomas B. MacMillan, Courtesy of Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College[28]

That very week in Washington, at a meeting of the Pan American Union[29], Roosevelt and his advisers spoke with hundreds of geologists and other representatives from Latin America — a resource-rich region that the U.S. saw as an answer to its strategic materials shortages.

Nervous about the history of U.S. imperial high-handedness in the region, some Latin Americans thought that their countries should seal off their resources to outside control, as Mexico had in nationalizing U.S. and European oil holdings[30] in 1938.

Japan’s advances in Southeast Asia after Pearl Harbor cut off rubber from the Dutch East Indies and Malaysia, prompting a rush for rubber in the Amazon and the development of synthetics. World War II posters urged Americans to conserve rubber for the war effort.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Courtesy of Northwestern University Libraries[31]

Japan’s advances in Southeast Asia after Pearl Harbor cut off rubber from the Dutch East Indies and Malaysia, prompting a rush for rubber in the Amazon and the development of synthetics. World War II posters urged Americans to conserve rubber for the war effort.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Courtesy of Northwestern University Libraries[31]

With European empires crumbling, Roosevelt faced a delicate diplomatic dance with Greenland. He wanted to maintain the appearance of neutrality, keep skeptical isolationists in Congress from revolting and give no provocations to Latin American anti-imperialists to cut off resources. Crucially, he also needed to avoid giving the resource-starved Japanese a legal justification to seize the oil-rich Dutch East Indies[32], now Indonesia – another European colony orphaned by the Nazi invasion.

Roosevelt’s solution: enlist Coast Guard “volunteers”[33] to guard Ivittuut. By the end of the summer, long before the U.S. officially entered the war, 15 sailors[34] resigned from their ships and took up residence near the mine.

Seeing Greenland as crucial to US security

Roosevelt also got creative with geography.

In an April 12, 1940, press conference, just days after the Nazi invasion, he began to emphasize Greenland as part of the Western Hemisphere[35], more American than European, and thus falling under Monroe Doctrine protections[36]. To calm fears in Latin America, U.S. officials recast the doctrine[37] as development-oriented hemispheric solidarity[38].

Maj. William S. Culbertson, a former U.S. trade official speaking before the Army Industrial College in fall 1940, noted how the scramble for resources pulled the U.S. into a form of nonmilitary warfare[39]: “We are engaged at the present time in economic warfare with the totalitarian powers. Publicly, our politicians don’t state it quite as bluntly as that, but it is a fact.” For the rest of the century, the front line was just as likely a far-off mine as an actual battlefield.

On April 9, 1941, exactly a year after the Nazis seized Denmark, Kauffmann[40] met with U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull[41] to sign an agreement “on behalf of the King of Denmark” placing Greenland and its mines under the U.S. security blanket. At Narsarsuaq, on the island’s southern tip, the U.S. began constructing an airbase named “Bluie West One[42].”

An aerial view shows Bluie West One, a U.S. air base at Narsarsuaq, Greenland, in June 1942. Later, during the Cold War, the U.S. used Thule Air Base, now called Pituffik Space Base, in northwest Greenland as a key missile defense site because of its proximity to the USSR.

USAF Historical Research Agency[43]

An aerial view shows Bluie West One, a U.S. air base at Narsarsuaq, Greenland, in June 1942. Later, during the Cold War, the U.S. used Thule Air Base, now called Pituffik Space Base, in northwest Greenland as a key missile defense site because of its proximity to the USSR.

USAF Historical Research Agency[43]

During the rest of World War II and throughout the Cold War, Greenland would house several important U.S. military installations[44], including some that forced Inuit families[45] to relocate[46].

Critical minerals today

What transpired in Greenland in the 18 months before Pearl Harbor fit into a larger emerging pattern.

As the U.S. ascended to global leadership and realized that it couldn’t maintain military dominance without wide access to foreign materials, it began to redesign the global system of resource flows and the rules for this new international order.

A 1952 chart from the President’s Materials Policy Commission, established by President Harry Truman to study the security of U.S. raw materials during the Cold War. The group was commonly known as the Paley Commission.

Resources for Freedom: A Report to the President[47]

A 1952 chart from the President’s Materials Policy Commission, established by President Harry Truman to study the security of U.S. raw materials during the Cold War. The group was commonly known as the Paley Commission.

Resources for Freedom: A Report to the President[47]

It rejected the Axis’ “might makes right” territorial conquest for resources, but found other ways to guarantee American access to critical resources, including loosening trade restrictions in European colonies.

The U.S. provided a lifeline to the British with the destroyers-for-bases deal[48] in September 1940 and the Lend-Lease Act[49] in March 1941, but it also gained strategic military bases around the world. It used aid as leverage to also pry open the British Empire’s markets[50].

The result was a postwar world interconnected by trade and low tariffs, but also a global network of U.S. bases and alliances of sometimes questionable legitimacy designed in part to protect U.S. access to strategic resources[51].

President John F Kennedy meets with Mobutu Sese Seko of the former Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, at the White House in 1963. Starting in the 1940s, the African country provided the U.S. with cobalt and uranium, including for the Hiroshima bomb. CIA-supported coups in 1960 and 1965 helped put Mobutu, known for corruption, in power.

Keystone/Getty Images[52]

President John F Kennedy meets with Mobutu Sese Seko of the former Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, at the White House in 1963. Starting in the 1940s, the African country provided the U.S. with cobalt and uranium, including for the Hiroshima bomb. CIA-supported coups in 1960 and 1965 helped put Mobutu, known for corruption, in power.

Keystone/Getty Images[52]

During the Cold War, these global resources helped defeat the Soviet Union. However, these security imperatives also gave the U.S. license for support of authoritarian regimes in places like Iran[53], Congo and Indonesia.

America’s voracious appetite for resources also often displaced local populations and Indigenous communities, justified by the old claim[54] that they misused the resources around them. It left environmental damage from the Arctic to the Amazon.

Donald Trump’s son visited Greenland in 2025, shortly after the U.S. president began talking about wanting to control the island and its resources. The people with Donald Trump Jr., second from right, are wearing jackets reading ‘Trump Force One.’

Emil Stach/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images[55]

Donald Trump’s son visited Greenland in 2025, shortly after the U.S. president began talking about wanting to control the island and its resources. The people with Donald Trump Jr., second from right, are wearing jackets reading ‘Trump Force One.’

Emil Stach/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images[55]

Strategic resources have been at the center of the American-led global system for decades. But U.S. actions today are different. The cryolite mine was a working mine, rarer than today’s proposed critical mineral mines in Greenland, and the Nazi threat was imminent. Most important, Roosevelt knew how to gain what the U.S. needed without a “damn-what-the world-thinks” military takeover.

References

- ^ crucial to U.S. national security (history.state.gov)

- ^ Greenland (history.state.gov)

- ^ strategic minerals (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ industries relied upon (doi.org)

- ^ five American Coast Guard cutters set sail (www.mycg.uscg.mil)

- ^ protect the Ivittuut mine (www.smithsonianmag.com)

- ^ A Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation (www.herbblockfoundation.org)

- ^ oil (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ uranium (www.bbc.com)

- ^ rubber (www.rutgersuniversitypress.org)

- ^ Foreign materials fueled American global power (utpress.utexas.edu)

- ^ Courtesy of Wichita State University Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives. Walter H. and Olive Ann Beech Collection, wsu_ms97-02.3.9.1 (wichita.contentdm.oclc.org)

- ^ historian (www.macalester.edu)

- ^ through their purchasing (www.ucpress.edu)

- ^ national security needs (www.tamupress.com)

- ^ control of Greenland’s natural resources (www.youtube.com)

- ^ critical minerals (www.usgs.gov)

- ^ addressed a joint session of Congress (www.fdrlibrary.org)

- ^ Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography (digital.library.cornell.edu)

- ^ 50,000 planes a year (www.nationalmuseum.af.mil)

- ^ age of alloys (archive.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ Fenno Jacobs/Department of Defense (catalog.archives.gov)

- ^ aluminum formed 60% (mitpress.mit.edu)

- ^ over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,100 degrees Celsius) (wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm)

- ^ substitute for cryolite using fluorspar (us.macmillan.com)

- ^ Allied officials huddled (history.state.gov)

- ^ Four others (www.mycg.uscg.mil)

- ^ Thomas B. MacMillan, Courtesy of Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College (www.bowdoin.edu)

- ^ meeting of the Pan American Union (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ nationalizing U.S. and European oil holdings (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office, Courtesy of Northwestern University Libraries (dc.library.northwestern.edu)

- ^ legal justification to seize the oil-rich Dutch East Indies (doi.org)

- ^ enlist Coast Guard “volunteers” (history.state.gov)

- ^ 15 sailors (history.state.gov)

- ^ emphasize Greenland as part of the Western Hemisphere (www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu)

- ^ thus falling under Monroe Doctrine protections (doi.org)

- ^ recast the doctrine (upittpress.org)

- ^ hemispheric solidarity (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ a form of nonmilitary warfare (utpress.utexas.edu)

- ^ Kauffmann (cphpost.dk)

- ^ Secretary of State Cordell Hull (history.state.gov)

- ^ Bluie West One (search.worldcat.org)

- ^ USAF Historical Research Agency (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ U.S. military installations (www.npr.org)

- ^ Inuit families (theconversation.com)

- ^ relocate (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ Resources for Freedom: A Report to the President (babel.hathitrust.org)

- ^ destroyers-for-bases deal (www.usni.org)

- ^ Lend-Lease Act (www.archives.gov)

- ^ pry open the British Empire’s markets (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ protect U.S. access to strategic resources (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ Keystone/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ places like Iran (www.amu.apus.edu)

- ^ justified by the old claim (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ Emil Stach/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

Authors: Thomas Robertson, Visiting Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, Macalester College