African-Americans' economic setbacks from the Great Recession are ongoing – and could be repeated

- Written by Vincent Adejumo, Lecturer of African American Studies, University of Florida

The financial crisis of 2009, the worst since the Great Depression[1], was hard on all Americans. But arguably no group felt its sting more than African-Americans, who were already the most economically and financially vulnerable segment of the population going into it.

Even today, a decade since the Great Recession hit, blacks still haven’t fully recovered and remain in a precarious financial condition. What’s worse, Wall Street and policymakers are beginning to worry another downturn may be on the horizon[2].

I teach a class[3] at the University of Florida called “Black Wall Street,” in which we explore the issue of capitalism as it pertains to African-Americans and examine historical data on income and wealth. In a nutshell, the numbers show blacks are woefully behind other groups and may never emerge from their rut if political leaders don’t do something about it soon.

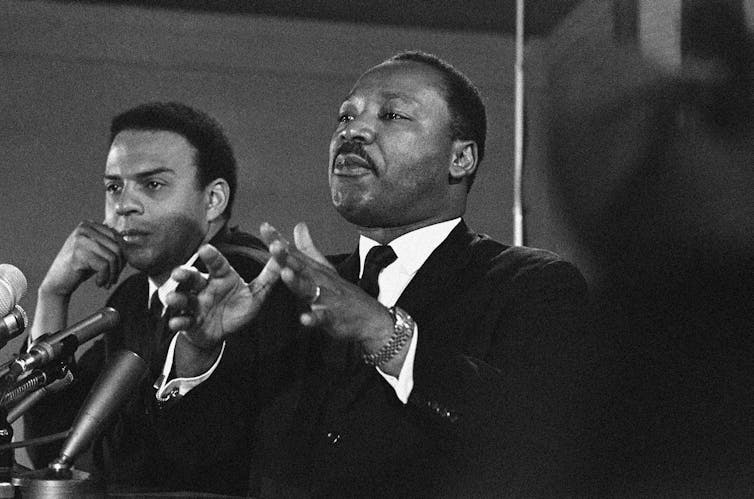

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. often spoke of economic justice.

AP Photo[4]

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. often spoke of economic justice.

AP Photo[4]

‘He merely exists’

The notion that blacks are especially prone to financial instability in the U.S. economy is hardly a new revelation.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., for example, often highlighted[5] the particular plight of African-Americans in his crusade for civil rights. In 1967, during a speech in Harlem, he said, “If a man doesn’t have a job or an income, he has neither life nor liberty nor the possibility for the pursuit of happiness. He merely exists.”

The data before the Great Recession of 2008-2009 tell a stark story. In 2007, the average black family earned US$55,265[6], just 64 percent of a white, non-Hispanic household income of $86,732. For the poorest fifth of African-American families, the situation is even worse. They earned just 43 percent of the income of their white peers[7] in 2005.

Furthermore, more than 20 percent of African-Americans earned less than $15,000[8] a year in 2008, nearly or more than double that of whites, Asians and Hispanics.

African-Americans are also far more likely to be unemployed. In the years before the Great Recession hit in 2008, for example, the jobless rate among blacks was typically around 10 percent[9], more than double[10] what it was for whites.

Enter the Great Recession

Of course, the financial crisis was hard on everyone.

Millions not only lost their jobs but also had to contend with the prospect of defaulting on student loans[11] and unpaid credit card debt[12], and even foreclosure on their homes[13].

And yet again, the Great Recession hammered blacks harder than other Americans because of their financial vulnerability.

The unemployment rate, for example, peaked at 10 percent[14] in 2009 for all Americans. For African-Americans, it exceeded 16 percent[15] – compared with a little under 9 percent[16] for whites.

African-American family incomes also suffered more than whites’. The average black household earned $50,654 in 2010, 61 percent of a white family.

And even today, although black incomes have recovered, African-Americans are still making only 63 percent of what whites earn. Coupled with the net worth[17] and homeownership[18] figures not recovering and even regressed since the recession officially ended, it means that blacks are still vulnerable to future economic downturns.

In 2016, an African-American household had an average net worth[19] of just $138,200, compared with $933,700 for a white family. This number is particularly high due to the fact that the vast majority of American billionaires are white[20].

This can be partly explained by a sharp difference in the rate of homeownership – one of the key pathways to secure, long-term financial stability. For blacks, it’s just 42 percent[21] – down from a high of 48 percent in 2004[22] – compared with 73 percent for whites.

In addition, blacks tend to own less valuable homes[23] worth just $94,400 on average, versus $215,800 for whites.

As was the case during past recessions, houses with the least amount of equity and worth are ripe for foreclosure[24] and owners of these houses have less opportunity to use their home as collateral in an emergency.

This lack of capital also forces African-Americans to incur more credit card debt[25] than whites. And so even the slightest emergency in an economic downturn would result in a weakened ability to meet financial obligations.

The black unemployment rate spiked after the Great Recession and is still twice as high as it is for whites.

Reuters/Fred Prouser[26]

The black unemployment rate spiked after the Great Recession and is still twice as high as it is for whites.

Reuters/Fred Prouser[26]

Dismal data

But beyond income and wealth, if you look at post-secondary education attainment[27], business and enterprise development[28], rates of divorce[29], single parent-headed households[30] and health disparities[31], you’ll see the same picture of African-Americans being left behind.

If these trends continue, the median wealth of black households – as opposed to the average or mean figures mentioned above – would fall from $1,700[32] as of 2013 to zero by 2053. For whites, median wealth is forecast to climb from $116,000 to $137,000.

I believe the central link tying all these data points together are the racist policies that have been entrenched in America’s financial, economic and educational fabric since the beginning. Examples include Jim Crow laws[33] as it pertains to legal separation by race in public institutions and redlining policies[34] concerning housing, which further allowed legal barriers to be put in place to impede the upward mobility of African-Americans.

If these problems aren’t addressed, I fear African-Americans may not have another chance to ever becoming equal economic players in this country. The further they slide financially, the harder it will be to reverse the decline. Another recession may make it irreversible.

And in Dr. King’s words, blacks would merely be existing.

References

- ^ financial crisis of 2009, the worst since the Great Depression (theconversation.com)

- ^ another downturn may be on the horizon (theconversation.com)

- ^ teach a class (afam.clas.ufl.edu)

- ^ AP Photo (www.apimages.com)

- ^ often highlighted (www.blackenterprise.com)

- ^ average black family earned US$55,265 (www.census.gov)

- ^ just 43 percent of the income of their white peers (www.epi.org)

- ^ earned less than $15,000 (www.census.gov)

- ^ typically around 10 percent (www.statista.com)

- ^ more than double (www.statista.com)

- ^ student loans (www.marketwatch.com)

- ^ credit card debt (finance.yahoo.com)

- ^ foreclosure on their homes (www.ipr.northwestern.edu)

- ^ peaked at 10 percent (tradingeconomics.com)

- ^ exceeded 16 percent (www.statista.com)

- ^ little under 9 percent (www.statista.com)

- ^ net worth (apps.urban.org)

- ^ homeownership (www.census.gov)

- ^ had an average net worth (www.federalreserve.gov)

- ^ vast majority of American billionaires are white (www.statista.com)

- ^ it’s just 42 percent (www.usatoday.com)

- ^ high of 48 percent in 2004 (www.census.gov)

- ^ tend to own less valuable homes (www.federalreserve.gov)

- ^ are ripe for foreclosure (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ incur more credit card debt (www.federalreserve.gov)

- ^ Reuters/Fred Prouser (pictures.reuters.com)

- ^ post-secondary education attainment (nces.ed.gov)

- ^ business and enterprise development (www.nber.org)

- ^ rates of divorce (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ single parent-headed households (datacenter.kidscount.org)

- ^ health disparities (www.hsph.harvard.edu)

- ^ would fall from $1,700 (prosperitynow.org)

- ^ Jim Crow laws (www.pbs.org)

- ^ redlining policies (www.washingtonpost.com)

Authors: Vincent Adejumo, Lecturer of African American Studies, University of Florida