How do scientists hunt for dark matter? A physicist explains why the mysterious substance is so hard to find

- Written by David Joffe, Associate Professor of Physics, Kennesaw State University

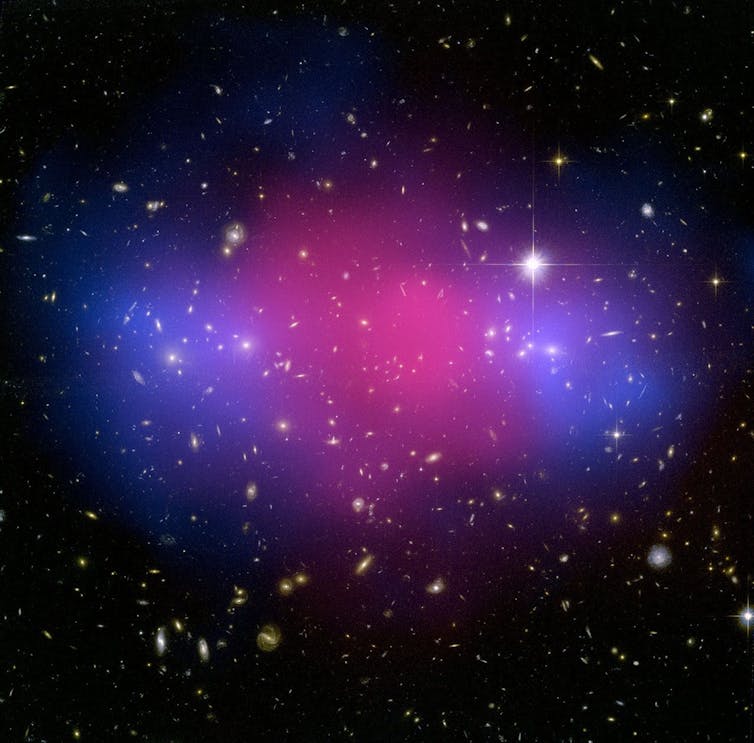

More recently, scientists have combined optical telescopes[12] that observe visible light with X-ray telescopes. Optical telescopes can take pictures of galaxies as they move and rotate. Sometimes, galaxies in these images are distorted or magnified by gravity coming from large masses in front of them. This phenomenon is called gravitational lensing[13], which is when the gravity around a very heavy object is so strong that it bends the light passing by it, acting like a lens.

X-ray telescopes[14], on the other hand, can see the clusters of hot gases[15] that surround galaxies. By combining these two telescopes, astronomers can see galaxies as well as the gases surrounding them – all the observable matter. Then, they can compare these images with the optical results. If there’s more gravitational lensing seen than what could be caused by the gas, there must be more mass hiding somewhere and causing the lensing.

How we might be able to see dark matter

Unfortunately, all this tells astronomers only that dark matter must be there, not what it really is. The evidence for dark matter is all based on how it interacts with gravity at very large scales. It’s still “dark” to scientists in the sense that it hasn’t interacted directly with any measurement devices.

The good news is that light and gravity aren’t the only forces in the universe. A force called the weak force[17] might be able to interact directly with dark matter and give scientists a direct signal to observe. Most of the ideas about what the dark matter might be include the possibility of it interacting through the weak force, converting energy into signals that are visible.

The weak force is not observable at normal scales of distance. But for objects the size of an atom’s nucleus[18] or smaller, it can change[19] one type of subatomic particle into another. The weak force can also transfer energy and momentum at very short distances – this is the main effect scientists hope to observe with dark matter. These processes might be extremely rare, but in theory they should be possible to see.

Most experiments looking to see dark matter directly are searching for signals of rare weak interactions in an underground detector[20], or for gamma rays that can be seen in a special gamma-ray telescope[21].

In either case, a signal from dark matter would likely be very faint, resulting from an interaction that can’t be explained any other way, or a signal that doesn’t seem to have any other possible source. Even if the effect is faint, it might still be possible to observe, and any such signal would be an exciting step forward in being able to see the dark matter more directly.

In the end, it may be a combination of signals from experiments deep underground, in particle colliders, and different types of telescopes that finally lets scientists see dark matter more directly. Whichever technology ends up being successful, hopefully sometime soon the matter that makes up our universe will be a little less dark.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com[22]. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

References

- ^ Curious Kids (theconversation.com)

- ^ CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com (theconversation.com)

- ^ Dark matter (theconversation.com)

- ^ I’m a physicist (scholar.google.com)

- ^ looking for signals (theconversation.com)

- ^ dark matter (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ Fritz Zwicky (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Coma Cluster (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ Vera Rubin (theconversation.com)

- ^ spiral galaxies (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScl/AURA); Acknowledgement: K. Cook (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory) (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ optical telescopes (letstalkscience.ca)

- ^ gravitational lensing (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ X-ray telescopes (www.britannica.com)

- ^ clusters of hot gases (theconversation.com)

- ^ NASA, ESA, CXC, M. Bradac (University of California, Santa Barbara), and S. Allen (Stanford University) (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ the weak force (www.energy.gov)

- ^ atom’s nucleus (www.energy.gov)

- ^ it can change (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ in an underground detector (theconversation.com)

- ^ gamma-ray telescope (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com (theconversation.com)

Authors: David Joffe, Associate Professor of Physics, Kennesaw State University