Women have been mapping the world for centuries – and now they’re speaking up for the people left out of those maps

- Written by Melinda Laituri, Professor Emeritus of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, Colorado State University

Although women have always been part of the mapping landscape, their contributions to cartography have long been overlooked[1].

Mapmaking has traditionally featured men, from Mercator’s projection of the world[2] in the 1500s to land surveyors such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson[3] mapping property in the 1700s, to Roger Tomlinson’s development of geographic information systems[4] in the 1960s. Cartography and related geospatial technologies fields continue to be male-dominated[5].

But as a geographer and specialist[6] in geographic information systems[7], I have observed how opportunities for women as mapmakers have changed over the past five decades. The advent of technologies such as geographic information systems has increased education, employment and research opportunities for women, making mapmaking more accessible.

The female landscape

Women have long been essential to how people see and understand the world. The concept of Mother Earth or Mother Nature[8] as the center of the universe and source of all life spans Indigenous cultures around the globe.

In the 20th century, the scientific community and environmental activists adopted the term Gaia[9] – the Greek goddess personifying the Earth, the mother of all deities – to reflect the notion of the Earth as a living system. Gaia is represented as female and understood as a guiding force in maintaining the atmosphere, oceans and climate.

The representation of land as woman was reshaped with the rise of nationalism when the terms “fatherland” and “motherland”[10]took on distinct meanings. Fatherland implied heritage and tradition, while motherland suggests place of birth and sense of belonging. These gendered constructs appear across cultures[11].

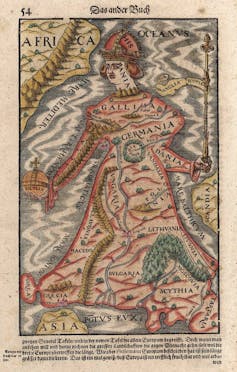

Another aspect of the gendered nature of cartography is the way maps used female forms to portray features. Anthropomorphic maps from the 16th through 19th centuries demonstrate how cartographers used female figures to depict European countries[13]. For example, cartographer Johannes Putsch’s “Europa Regina[14],” originally drawn in 1537, set the template for later maps in which nations are depicted as women in various poses and different states of dress – or undress – though they don’t actually correspond closely to the actual shapes of real landforms.

These maps reflect shifting cultural and political meanings attached to territory and power. The female landscape, or woman as map, is often used to portray countries as active, aggressive or supine, depending upon the status of the nation state in relation to war and peace and the stereotypes of a country.

Technology and women’s roles in mapmaking

While the technical contributions women have made to mapping span the entire history of cartography, they are difficult to identify and document. But a closer look reveals the variety of roles women have played in mapmaking.

One of the earliest known examples of a map made by a woman dates to the fourth century, when the sister of the prime minister of the Han Dynasty in China embroidered a map on silk[15].

During the 15th and 16th centuries, women were employed to color maps and contribute artistic details[16] to borders. Many women cartographers used only a first initial and last name, obscuring their gender and making their work difficult to trace.

The 18th century brought the advent of printing[17], which opened new avenues for women to participate as engravers of copper plates, publishers of maps, and globemakers.

By the 19th century, cartography became part of formal education for women in North America, where the intersection of embroidery and geography[18] produced fabric globes and linen maps. This was later followed by drawing and coloring maps as access to paper and pencils improved.

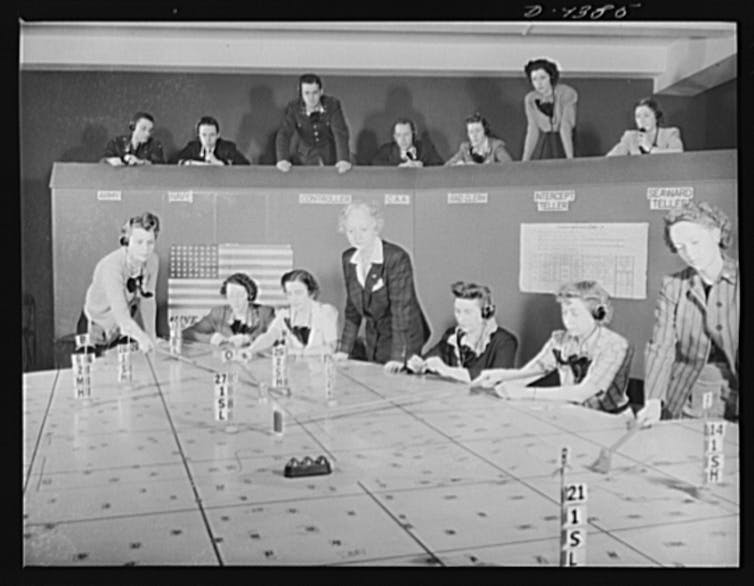

World War II ushered in a new era of opportunity for women in the U.S., as they were recruited to fill critical roles in cartographic development while men were sent to war. Known as Millie the Mapper or the Military Mapping Maidens[19], women produced topographic maps[20], interpreted aerial photography and helped advance photogrammetry, the use of photos to make 3D models of the Earth’s topography.

Building on the expanding role of women in cartography, in the 1950s Evelyn Pruitt of the U.S. Office of Naval Research coined the term remote sensing[22], referring to the use of satellite imagery to observe, measure and map the Earth. In the same period, mathematician Gladys West developed the mathematical models for global positioning systems, known as GPS[23].

Women creating the maps

Women have also overseen the creation of maps in a number of ways.

Indigenous matriarchal societies expressed spatial information through different forms of cartography. These includes songs, dances and rituals[24] that identified important communal resources such as springs, sacred groves and migration paths.

The development of European cartography was driven by the Age of Exploration from the 15th to 17th centuries and entrepreneurial activities associated with reproducing and selling maps. Women often assumed these roles after the deaths of their husbands[25], ensuring the continuation of family businesses.

Not only kings but queens also directed what maps were needed. For example, Queen Elizabeth I commissioned the 1579 Atlas of England and Wales[26], one of the first national atlases. It rendered a map of the entire country, accessible from home or a reading room.

Women setting the direction of maps

While early maps positioned women primarily as symbolic bodies to project political meaning or as supporters of larger mapping enterprises, contemporary cartography reveals a different dynamic between gender and maps: There is a lack of geographic data on issues affecting women, including health, safety and planning for the future.

For example, women are disproportionately affected by disasters[27], including through a heightened risk of experiencing gender-based violence. Geographic analyses reveal a persistent gender gap in datasets[28], which often lack information on women’s health and daily needs, reproductive services or child care centers.

Studies have shown that the development of geospatial technologies and open mapping platforms are dominated by men[29]. In situations such as disasters, having a diversity of perspectives in mapmaking is essential to serving the needs of the community.

Millions of people are missing from maps.Creating maps that specifically reflect women’s needs is foundational for women to fully participate in 21st-century mapmaking. In the past decade, several programs and organizations have been working to reflect women’s contributions to cartography and demonstrate how collective action can make a difference.

For example, African Women in GIS[30] hosts workshops to elevate women’s perspectives and mapping needs, putting mobile mapping technology in women’s hands. GeoChicas[31] and YouthMappers’ Let Girls Map[32] empower women to make maps through training and education that address the digital divide. Women in GIS[33] and Women+ in Geospatial[34] build community in mapmaking through professional networks. Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team[35] amplifies women’s voices to inform geospatial approaches to mapmaking and empowering women’s mapmaking contributions.

Never have there been more opportunities for women to participate in mapmaking, and never has women’s role in mapmaking been as important to address the intractable issues societies face around the world.

References

- ^ have long been overlooked (www.wlupress.wlu.ca)

- ^ Mercator’s projection of the world (education.nationalgeographic.org)

- ^ land surveyors such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson (pdhacademy.com)

- ^ geographic information systems (www.bcs.org)

- ^ continue to be male-dominated (geospatialworld.net)

- ^ geographer and specialist (scholar.google.com)

- ^ geographic information systems (education.nationalgeographic.org)

- ^ Mother Earth or Mother Nature (archive.org)

- ^ adopted the term Gaia (nautil.us)

- ^ “fatherland” and “motherland” (doi.org)

- ^ appear across cultures (www.dictionary.com)

- ^ Sebastian Münster/Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ used female figures to depict European countries (repository.lsu.edu)

- ^ Europa Regina (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ embroidered a map on silk (www.routledge.com)

- ^ color maps and contribute artistic details (www.leventhalmap.org)

- ^ advent of printing (www.leventhalmap.org)

- ^ intersection of embroidery and geography (www.routledge.com)

- ^ Millie the Mapper or the Military Mapping Maidens (blogs.loc.gov)

- ^ topographic maps (gisgeography.com)

- ^ Alfred T Palmer/Office of War Information via Library of Congress (www.loc.gov)

- ^ coined the term remote sensing (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ mathematical models for global positioning systems, known as GPS (www.vsu.edu)

- ^ songs, dances and rituals (theconversation.com)

- ^ assumed these roles after the deaths of their husbands (www.leventhalmap.org)

- ^ commissioned the 1579 Atlas of England and Wales (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ disproportionately affected by disasters (doi.org)

- ^ persistent gender gap in datasets (odihpn.org)

- ^ dominated by men (doi.org)

- ^ African Women in GIS (www.linkedin.com)

- ^ GeoChicas (geochicas.github.io)

- ^ YouthMappers’ Let Girls Map (www.youthmappers.org)

- ^ Women in GIS (womeningis.wildapricot.org)

- ^ Women+ in Geospatial (womeningeospatial.org)

- ^ Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (www.hotosm.org)

Authors: Melinda Laituri, Professor Emeritus of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, Colorado State University