As hunting declines, efforts grow to broaden the funding base for wildlife conservation

- Written by Lincoln Larson, Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University

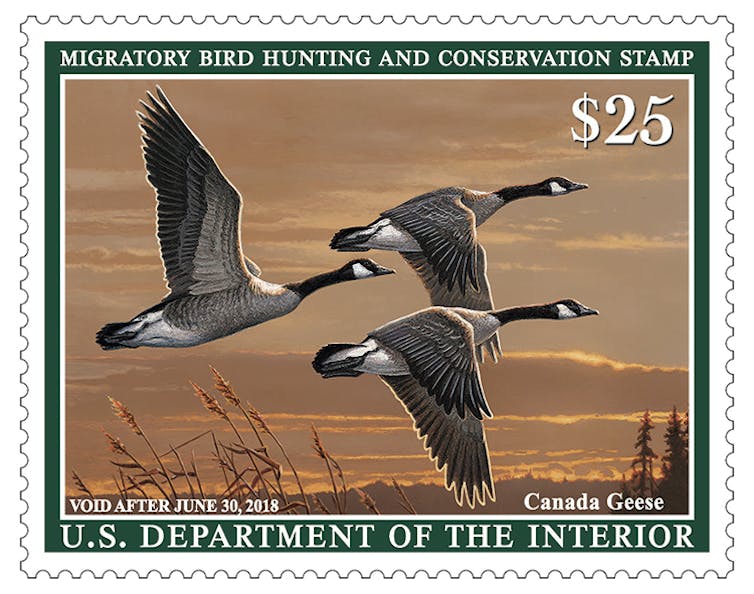

Hunting is a seasonal ritual for more than 11 million Americans[1] in fall and winter. For those whose quarry includes ducks, geese or other waterfowl, one essential item is a Federal Duck Stamp[2] – one of the most innovative and influential conservation initiatives in U.S. history.

For more than 80 years, federal law has required all hunters age 16 and older to buy and carry the current season’s duck stamp in the field. The stamp costs US$25 and inspires an annual art and design contest[3]. Ninety-eight cents of every dollar from stamp purchases goes into a fund to protect wetlands and wildlife habitat. Since the 1930s, duck stamps have raised over $1 billion[4] to support the National Wildlife Refuge System[5].

Duck stamps represent a “user pay, user benefit” approach to funding conservation that is unique to North America, with hunters as the centerpiece[6]. But this model works only if people hunt, and the number of hunters in the United States has significantly declined[7] in recent decades.

My research[8] on connections between people and nature shows that demographic and cultural trends are reshaping the modern landscape[9] for hunting and other outdoor recreation activities. For wildlife managers and outdoor advocates, these shifts are raising questions about who will pay for conservation in the future[10].

The 2017-2018 federal duck stamp, designed by James Hautman.

USFWS, CC BY-ND[11][12]

The 2017-2018 federal duck stamp, designed by James Hautman.

USFWS, CC BY-ND[11][12]

Taxes and license fees

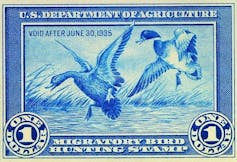

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act[13] in 1934. The program was proposed by Jay N. “Ding” Darling[14], a cartoonist, conservation pioneer and outdoorsman. Darling headed the agency that would become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 1934 to 1936 and drew the first duck stamp.

The first federal duck stamp, designed by Jay N. ‘Ding’ Darling and issued in 1934.

USFWS, CC BY-ND[15][16]

The first federal duck stamp, designed by Jay N. ‘Ding’ Darling and issued in 1934.

USFWS, CC BY-ND[15][16]

Other user-pay measures followed. The 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act[17] imposed an 11 percent federal excise tax on sales of hunting gear and ammunition to support state wildlife conservation efforts. In 1950 the Dingell-Johnson Act[18] placed a similar tax on fishing equipment and motor boat fuel. Today these taxes, along with duck stamps and license fees, raise roughly 60 percent of all revenue to support fish and wildlife conservation efforts yearly.

Broadening the conservation funding base

License fees and gear taxes target specific groups (hunters and anglers), but duck stamps could also appeal to other potential buyers, such as birdwatchers, photographers and stamp collectors. They serve as an annual pass to U.S. National Wildlife Refuges that charge entrance fees, and organizations such as the American Birding Association encourage birders to “make their voices heard[19]” in wildlife conservation by purchasing duck stamps. However, there is very little information about whether and why birders actually buy the stamps.

To answer these questions, I worked with graduate student Nathan Shipley[20], NCSU colleague Caren Cooper[21] and researchers from the National Audubon Society[22] to survey thousands of birdwatchers participating in the society’s annual Christmas Bird Count[23]. We found[24] that just 14 percent of nonhunting bird count participants had purchased duck stamps in the past two years. Even among specialized birdwatchers who invested substantial time and money in birding, only 36 percent had bought the stamps.

These low numbers may reflect a general lack of knowledge about duck stamps and their purpose. For example, studies have shown that even waterfowl hunters know very little[25] about the duck stamp’s role in wildlife conservation. Other research has found low awareness[26] among nonhunting outdoor advocates about hunting’s links to environmental stewardship and conservation. And birders may be reluctant to buy something historically linked to hunting.

Wetland conservation video produced by Ducks Unlimited, a nonprofit formed by sportsmen in 1937 that conserves, restores and manages wetlands and associated habitats for North America’s waterfowl.Despite ideological differences, however, both birdwatchers and hunters are more likely than nonrecreationists[27] to engage in pro-environmental behaviors such as joining conservation organizations, volunteering to enhance wildlife habitat on public lands and donating money to support conservation. But while birdwatchers may be just as eager to contribute to conservation as hunters, our research indicates that duck stamps are not currently an effective way to financially engaging the birding community.

Recruiting new hunters

Since 2011, the number of big game hunters in the United States has decreased by 20 percent, and the total number of hunters has declined by over 2 million[28]. This trend leaves wildlife managers two primary options for boosting conservation funding: Attract new hunters or find other revenue sources.

The first strategy, often referred to as R3 – recruitment, retention and reactivation – is rapidly gaining traction in the wildlife management world. My colleagues and I have spent much of the past five years studying nontraditional pathways into hunting[29], including growing interest in links between wild game meat and the local food movement[30].

Adam Ahlers of Kansas State University guides students on their first hunting experience.

Haley Ahlers, CC BY-ND[31]

Adam Ahlers of Kansas State University guides students on their first hunting experience.

Haley Ahlers, CC BY-ND[31]

Our current project[32], which spans 23 states, is exploring the potential impact of R3 efforts focused on college students. Preliminary results suggest that over 70 percent of college students support hunting. Roughly one in six plan to hunt in the future, and one in four would consider trying it.

Finding new revenue streams

However, other funding sources are also needed. As one example, in 2009 thousands of wildlife professionals, hunters, birdwatchers and other recreationists endorsed the Teaming with Wildlife Act[33], which would have introduced a new excise tax on nonconsumptive recreation gear such as binoculars, tents and kayaks. The bill failed to pass, largely due to limited support from retailers.

In 2016, the Blue Ribbon Panel on Sustaining America’s Fish & Wildlife Resources – a bipartisan group comprising leaders across government, industry and the nonprofit sector – released a report[34] urging Congress to dedicate up to $1.3 billion annually in revenues from energy production and mining on federal lands and waters to support wildlife conservation. This recommendation has been integrated into the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act[35], which was introduced in the House[36] in December 2017 and the Senate[37] in July 2018, and attracted bipartisan support in both chambers.

This approach also appears to be popular among future generations of voters. In our study of college students, we asked participants to evaluate nine potential options for funding wildlife conservation. The preferred strategy across all demographic subgroups, supported by over 80 percent of students, was requiring “companies that profit from natural resource extraction to contribute a portion of their annual revenue to conservation.”

Through duck stamps, excise taxes and license purchases, hunters (and anglers) will continue to play a critical role in the future of funding conservation. But other stakeholder groups, from birdwatchers to energy companies, can also contribute. If Congress passes the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, it could open a new chapter in North America’s innovative history of funding wildlife conservation.

References

- ^ more than 11 million Americans (www.doi.gov)

- ^ Federal Duck Stamp (www.fws.gov)

- ^ art and design contest (www.fws.gov)

- ^ over $1 billion (www.fws.gov)

- ^ National Wildlife Refuge System (www.fws.gov)

- ^ hunters as the centerpiece (doi.org)

- ^ significantly declined (wsfrprograms.fws.gov)

- ^ My research (scholar.google.com)

- ^ reshaping the modern landscape (doi.org)

- ^ who will pay for conservation in the future (www.npr.org)

- ^ USFWS (www.fws.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act (www.fws.gov)

- ^ Jay N. “Ding” Darling (www.fws.gov)

- ^ USFWS (www.fws.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Pittman-Robertson Act (wsfrprograms.fws.gov)

- ^ Dingell-Johnson Act (wsfrprograms.fws.gov)

- ^ make their voices heard (www.aba.org)

- ^ Nathan Shipley (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ Caren Cooper (faculty.cnr.ncsu.edu)

- ^ National Audubon Society (www.audubon.org)

- ^ Christmas Bird Count (www.audubon.org)

- ^ We found (doi.org)

- ^ know very little (doi.org)

- ^ low awareness (doi.org)

- ^ are more likely than nonrecreationists (doi.org)

- ^ declined by over 2 million (www.census.gov)

- ^ nontraditional pathways into hunting (doi.org)

- ^ local food movement (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ current project (drive.google.com)

- ^ Teaming with Wildlife Act (www.govtrack.us)

- ^ a report (www.fishwildlife.org)

- ^ Recovering America’s Wildlife Act (wildlife.org)

- ^ House (www.congress.gov)

- ^ Senate (www.congress.gov)

Authors: Lincoln Larson, Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University