How stereo was first sold to a skeptical public

- Written by Jonathan Schroeder, William A. Kern Professor in Communications, Rochester Institute of Technology

When we hear the word “stereo” today, we might simply think of a sound system, as in “turn on the stereo.”

But stereo actually is a specific technology, like video streaming or the latest espresso maker.

Sixty years ago, it was introduced for the first time.

Whenever a new technology comes along – whether it’s Bluetooth, high-definition TV or Wi-Fi – it needs to be explained, packaged and promoted to customers who are happy with their current products.

Stereo was no different. As we explore in our recent book, “Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America[1],” stereo needed to be sold to skeptical consumers. This process involved capturing the attention of a public fascinated by space-age technology using cutting-edge graphic design, in-store sound trials and special stereo demonstration records.

The rise of ‘hi-fi’ sound

In 1877, Thomas Edison introduced the phonograph[2], the first machine that could reproduce recorded sound. Edison used wax cylinders to capture sound and recorded discs became popular in the early 20th century.

By the 1950s, record players, as they came to be called, had become a mainstay of many American living rooms. These were “mono,” or one-channel, music systems. With mono, all sounds and instruments were mixed together. Everything was delivered through one speaker.

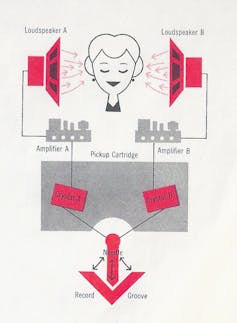

Stereophonic sound, or stereo, was an important advance in sound reproduction. Stereo introduced two-channel sound, which separated out elements of the total sound landscape and changed the experience of listening.

Audio engineers had sought to improve the quality of recorded sound in their quest for “high fidelity[3]” recordings that more faithfully reproduced live sound. Stereo technology recorded sound and played it back in a way that more closely mimicked how humans actually hear the world around them.

A graphic detail, from an RCA inner sleeve, shows listeners how new stereo technology operates.

From the collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

A graphic detail, from an RCA inner sleeve, shows listeners how new stereo technology operates.

From the collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

British engineer Alan Dower Blumlein[4] paved the way for two channel recording in the 1930s. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that stereo technology was incorporated into movie theaters, radios and television sets.

With stereo, the sound of some instruments could come from the left speaker, the sound of others from the right, imitating the setup of a concert orchestra. It also was possible to shift a particular sound from left to right or right to left, creating a sense of movement.

Although Audio-Fidelity Records offered a limited edition stereo record for industry use in 1957, consumers needed to wait until 1958 for recordings with stereo sound to become widely available for the home.

A sonic ‘arms race’ to sell the sound

When stereo records were introduced to the mass market, a “sonic arms race” was on. Stereo was aggressively promoted as the latest technological advancement that brought sophisticated sound reproduction to everyone.

Each of the era’s major record labels started pushing stereo sound. Companies like Columbia, Mercury and RCA, which sold both stereo equipment and stereo records, moved to convince consumers that stereo’s superior qualities were worth further investment.

A key challenge for selling stereo was consumers’ satisfaction with the mono music systems they already owned. After all, adopting stereo meant you needed to buy a new record player, speakers and a stereo amplifier.

Something was needed to show people that this new technology was worth the investment. The “stereo demonstration” was born – a mix of videos, print ads and records designed to showcase the new technology and its vibrant sound.

Record companies were convinced the public simply needed to be exposed to the new technology to be sold on it.Stereo demonstration records showed off the innovative qualities of a new stereo system, with tracks for “balancing signals” or doing “speaker-response checks.” They often included compelling, detailed instructional notes to explain the new stereo sound experience.

Stereo’s potential and potency stormed retail showrooms and living rooms.

Curious shoppers could hear trains chugging from left to right, wow at the roar of passing war planes, and catch children’s energetic voices as they dashed across playgrounds. Capitol Records released “The Stereo Disc,” which featured “day in the life” ambient sounds such as “Bowling Alley” and “New Year’s Eve at Times Square” to transport the listener out of the home and into the action.

A particularly entertaining example of the stereo demonstration record is RCA Victor’s “Sounds in Space.” Appearing a year after the successful launch of the Soviet’s Sputnik satellite in 1957[5], this classic album played into Americans’ growing interest in the space race raging between the two superpowers.

RCA Victor’s ‘Sounds in Space’ demonstration album.

From the collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

RCA Victor’s ‘Sounds in Space’ demonstration album.

From the collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

“The age of space is here,” the record begins, “and now RCA Victor brings you ‘Sounds in Space.’” Narrator Ken Nordine’s charismatic commentary[6] explains stereophonic sound as his voice “travels” from one speaker channel to another, by the “the miracle of RCA stereophonic sound.”

Record companies also released spectacular stereo recordings of classical music.

Listening at home began to reproduce the feeling of hearing music live in the concert hall, with stereo enhancing the soaring arias of Wagner’s operas and the explosive thundering cannons of Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture.”

Today, rousing orchestral works from the early stereo era, such as RCA Victor’s “Living Stereo” albums from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra[7], are considered some of the finest achievements of recorded sound.

Visualizing stereo

Stereo demonstration records, in particular, featured attractive, modern graphic design. Striking, often colorful, lettering boasted titles such as “Stereorama,” “360 Sound” and “Sound in the Round.”

An Epic Records demonstration album cover features a rainbow of sound.

Collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

An Epic Records demonstration album cover features a rainbow of sound.

Collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

Some stereo demonstration records focused on the listening experience. The ecstatic blond woman on the cover of Warner Bros. Records’ “How to Get the Most Out of Your Stereo” sports a stethoscope and seems thrilled to hear the new stereo sound. World Pacific Records “Something for Both Ears!” offers a glamorous model with an ear horn in each ear, mimicking the stereo effect.

Record companies tried to hook listeners with demonstration records featuring vivid graphics.

From the collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

Record companies tried to hook listeners with demonstration records featuring vivid graphics.

From the collection of Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder, Author provided

These eye-catching design elements became an important part of the record companies’ visual branding. All were deployed to grab the attention of customers and help them visualize how stereo worked. Now they’ve become celebrated examples of midcentury album cover art.

By the late 1960s, stereo dominated sound reproduction, and album covers no longer needed to indicate “stereo” or “360 Sound.” Consumers simply assumed that they were buying a stereo record.

Today, listeners can enjoy multiple channels with surround sound by purchasing several speakers for their music and home theater systems. But stereo remains a basic element of sound reproduction.

As vinyl has enjoyed a surprising comeback lately[8], midcentury stereo demonstration records are enjoying new life as retro icons – appreciated as both a window into a golden age of emerging sound technology and an icon of modern graphic design.

References

- ^ Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America (www.designedforhifiliving.com)

- ^ introduced the phonograph (www.loc.gov)

- ^ high fidelity (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Alan Dower Blumlein (www.telegraph.co.uk)

- ^ the successful launch of the Soviet’s Sputnik satellite in 1957 (www.history.com)

- ^ charismatic commentary (www.youtube.com)

- ^ RCA Victor’s “Living Stereo” albums from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (csosoundsandstories.org)

- ^ As vinyl has enjoyed a surprising comeback lately (theconversation.com)

Authors: Jonathan Schroeder, William A. Kern Professor in Communications, Rochester Institute of Technology

Read more http://theconversation.com/how-stereo-was-first-sold-to-a-skeptical-public-103668