65,000 Pennsylvania kids have a parent in prison or jail − here’s what research says about the value of in-person visits

- Written by Julie Poehlmann, Professor of Human Development & Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Across Pennsylvania, an estimated 65,459 children have a parent in jail or prison. That’s according to a recent email inquiry to the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. Nationwide, nearly half of adults[1] have experienced a close family member being in jail or prison, and 1 in 14 children[2] have lost a parent who was living with them to incarceration.

In May 2025, state Rep. Andre Carroll, whose district covers parts of northwest Philadelphia[3], and whose own father was incarcerated[4] when Carroll was a child, introduced PA House Bill 1506[5]. The proposed law “focuses on improving communication between incarcerated individuals and their families” by making phone calls and other communication with incarcerated individuals free. It would also prohibit the replacement of in-person visits with other forms of communication such as video calls.

I’m a psychologist and professor of human development and family studies who has studied children with incarcerated parents[6] for more than 25 years.

In 2020, when in-person visits were stopped at jails and prisons due to the COVID-19 pandemic, my colleagues and I interviewed 71 jailed parents[7] in Wisconsin to understand the strengths and challenges of remote video visits with their children.

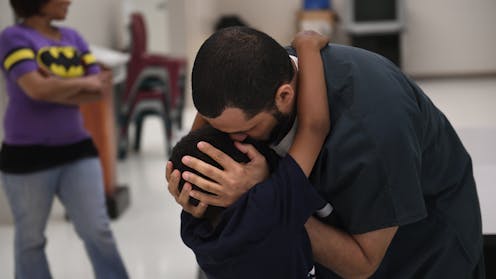

The parents we spoke with strongly preferred in-person visits, where they are allowed to touch and hug, over virtual ones.

“Contact means a lot,” one parent told us. “This type of stuff breaks families apart, not being able to see a person face to face or touch a person.”

Another parent said, “Video visits are good as it fits into their schedule, but they are not the same. … Giving your child a hug is worth a hundred video visits.”

These findings are still relevant today because many local jails across the country are using video visits as a replacement for in-person visits[8]. For example, an analysis of 40 county jails in Michigan found that 33 of them[9] banned in-person visits.

State and federal prisons generally have in-person visits, with video visits sometimes offered as a supplement.

Benefits for kids

Kids whose parents are in jail or prison are more likely to experience problems in health and well-being[11] compared to their peers, though a growing body of research shows that many children with incarcerated parents are resilient[12]. Resilience refers to the development of competence despite experiencing significant hardship[13] or stress.

In-person visits in particular[14] have been shown to strengthen parent-child relationships[15], which are a key[16] resilience factor[17].

In addition, research has shown that children benefit from visiting with their incarcerated parents when such visits are part of an intervention program[18] that includes, for example, mentoring programs[19] or child-friendly visits[20].

During child-friendly visits, children see their incarcerated parents face to face and can hug them, hold hands, be carried, or sit on their lap. They engage in meaningful activities together – such as playing games, reading together, doing art projects, or taking photos of themselves – that are designed to strengthen their relationship. They can also eat together, are free to move around the space, and are supported by trained staff.

In-person contact visits that allow touch are more developmentally appropriate[21] for children than noncontact visits. For young children who are not part of an intervention, visits with incarcerated parents behind plexiglass can be confusing[22]. The kids can see but not touch their parent, and they can only hear and speak to them through a device that looks like an old-fashioned telephone.

Benefits for parents

Incarcerated parents say that separation from their children is the most difficult part about being in prison or jail[23]. They frequently report symptoms of distress and depression, especially when they have little contact with their children[24].

More frequent parent-child contact during parental incarceration – and visiting in particular – is associated with better mental health, fewer behavioral infractions, better relationships with the child’s at-home caregiver and more parent-child contact[25] and better adjustment[26] after release.

Other studies have found links between more visits with children and less recidivism[27], which also benefits society as a whole.

Furthermore, a study of 507 adults incarcerated because of felony charges in a county jail in Virginia found that more frequent contact with family members during incarceration related to more family connectedness[28], which in turn predicted better mental health during the first year after release.

Barriers to contact

Despite the benefits of visiting and other forms of contact, barriers can prevent communication[30] from occurring regularly or at all.

Some of these barriers are economic. Supporting a loved one in prison or jail can be a major financial strain[31] on family members, and children in families experiencing more economic hardship are less likely to visit their incarcerated parents[32].

Some prisons charge exorbitant fees for video and phone calls[33]. The Prison Policy Initiative tracks the prices of phone calls[34] from prisons in each state. In 2021, the average cost of a 15-minute in-state phone call from a Pennsylvania prison was more than $3.

The racial disparities[35] in who is incarcerated mean that Black and Latino families disproportionately carry the financial load of incarceration-related expenses.

Other barriers involve distance that families live from the prison or jail, time and scheduling conflicts, and strict mail policies that allow incarcerated people to receive only postcards[36] or scanned copies of their mail[37]. Strained relationships between incarcerated parents and family members can further limit contact.

Keeping families connected

Transportation programs offered by the Pennsylvania Prison Society[38], an advocacy organization for people who are incarcerated and their families, and other groups can help when family finances are tight. PPS currently provides rides from Philadelphia to four state correctional institutions[39]. A round-trip bus ticket, which is usually $20, is free for children under 18.

In addition, some jails and prisons offer a limited number of free video visits or phone calls. The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections’ website indicates that incarcerated individuals can receive up to four in-person visits per month in addition to six no-cost video visits[40].

Other organizations are trying to make sure that children and other family members have a chance to stay connected to their incarcerated loved ones in positive ways. Earlier this year, nonprofit legal advocacy organizations helped children in two Michigan counties[41] file landmark civil rights lawsuits[42] that asserted a constitutional right to visit their parents in jail.

As an expert witness in these cases, I hope that they help more children get the “right to hug[43]” their incarcerated parents and raise awareness of the positive impacts that visits play in the current and future well-being of incarcerated individuals and their families.

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia[44].

References

- ^ nearly half of adults (everysecond.fwd.us)

- ^ 1 in 14 children (www.childtrends.org)

- ^ Philadelphia (theconversation.com)

- ^ father was incarcerated (www.andredcarroll.com)

- ^ PA House Bill 1506 (www.palegis.us)

- ^ studied children with incarcerated parents (scholar.google.com)

- ^ interviewed 71 jailed parents (kidswithincarceratedparents.com)

- ^ replacement for in-person visits (www.nbcnews.com)

- ^ 33 of them (www.prisonpolicy.org)

- ^ Paul Bersebach/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ problems in health and well-being (doi.org)

- ^ are resilient (doi.org)

- ^ development of competence despite experiencing significant hardship (doi.org)

- ^ In-person visits in particular (doi.org)

- ^ strengthen parent-child relationships (doi.org)

- ^ a key (doi.org)

- ^ resilience factor (doi.org)

- ^ part of an intervention program (doi.org)

- ^ mentoring programs (doi.org)

- ^ child-friendly visits (doi.org)

- ^ are more developmentally appropriate (www.urban.org)

- ^ can be confusing (doi.org)

- ^ most difficult part about being in prison or jail (doi.org)

- ^ little contact with their children (doi.org)

- ^ more parent-child contact (doi.org)

- ^ better adjustment (doi.org)

- ^ less recidivism (doi.org)

- ^ more family connectedness (doi.org)

- ^ AP Photo/David J. Phillip (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ barriers can prevent communication (doi.org)

- ^ major financial strain (www.wecantaffordit.us)

- ^ less likely to visit their incarcerated parents (doi.org)

- ^ exorbitant fees for video and phone calls (www.fcc.gov)

- ^ prices of phone calls (www.prisonpolicy.org)

- ^ racial disparities (doi.org)

- ^ postcards (www.prisonpolicy.org)

- ^ scanned copies of their mail (www.prisonpolicy.org)

- ^ Pennsylvania Prison Society (www.prisonsociety.org)

- ^ rides from Philadelphia to four state correctional institutions (www.prisonsociety.org)

- ^ six no-cost video visits (www.pa.gov)

- ^ in two Michigan counties (www.right2hug.org)

- ^ landmark civil rights lawsuits (www.right2hug.org)

- ^ right to hug (www.newyorker.com)

- ^ Philadelphia (theconversation.com)

Authors: Julie Poehlmann, Professor of Human Development & Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison