My thoughts are my password, because my brain reactions are unique

- Written by Wenyao Xu, Assistant Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Your brain is an inexhaustible source of secure passwords – but you might not have to remember anything. Passwords and PINs with letters and numbers are relatively easily hacked[1], hard to remember and generally insecure. Biometrics are starting to take their place, with fingerprints, facial recognition and retina scanning becoming common even in routine logins for computers, smartphones and other common devices.

They’re more secure because they’re harder to fake, but biometrics have a crucial vulnerability: A person only has one face, two retinas and 10 fingerprints. They represent passwords that can’t be reset if they’re compromised.

Like usernames and passwords, biometric credentials are vulnerable to data breaches. In 2015, for instance, the database containing the fingerprints of 5.6 million U.S. federal employees[2] was breached. Those people shouldn’t use their fingerprints to secure any devices, whether for personal use or at work. The next breach might steal photographs or retina scan data, rendering those biometrics useless for security.

Our[3] team[4] has been working with collaborators[5] at other institutions[6] for years, and has invented a new type of biometric that is both uniquely tied to a single human being and can be reset if needed.

Inside the mind

When a person looks at a photograph or hears a piece of music, her brain responds[7] in ways that researchers or medical professionals can measure with electrical sensors placed on her scalp. We have discovered that every person’s brain responds differently[8] to an external stimulus, so even if two people look at the same photograph, readings of their brain activity will be different.

This process is automatic and unconscious, so a person can’t control what brain response happens. And every time a person sees a photo of a particular celebrity, their brain reacts the same way – though differently from everyone else’s.

We realized that this presents an opportunity for a unique combination that can serve as what we call a “brain password[9].” It’s not just a physical attribute of their body, like a fingerprint or the pattern of blood vessels in their retina. Instead, it’s a mix of the person’s unique biological brain structure and their involuntary memory that determines how it responds to a particular stimulus.

Making a brain password

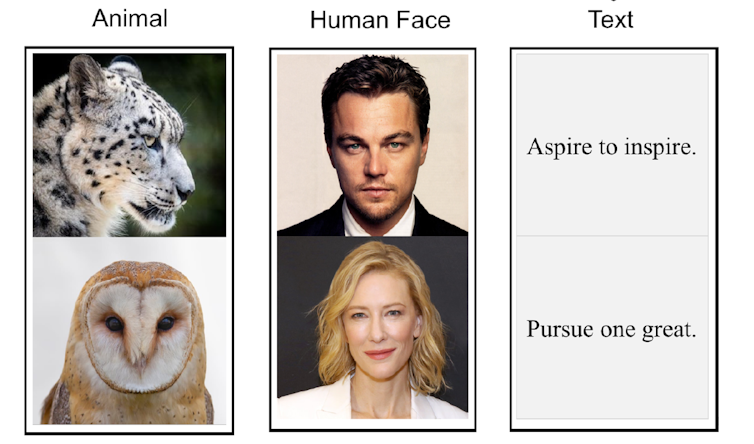

A person’s brain password is a digital reading of their brain activity while looking at a series of images. Just as passwords are more secure if they include different kinds of characters – letters, numbers and punctuation – a brain password is more secure if it includes brain wave readings of a person looking at a collection of different kinds of pictures.

A range of visual stimuli generates the best brain password.

Wenyao Xu, et al., CC BY-ND[10]

A range of visual stimuli generates the best brain password.

Wenyao Xu, et al., CC BY-ND[10]

To set the password, the person would be authenticated some other way – such as coming to work with a passport or other identifying paperwork, or having their fingerprints or face checked against existing records. Then the person would put on a soft comfortable hat or padded helmet with electrical sensors inside. A monitor would display, for example, a picture of a pig, Denzel Washington’s face and the text “Call me Ishmael,” the opening sentence of Herman Meville’s classic “Moby-Dick.”

The sensors would record the person’s brain waves. Just as when registering a fingerprint[11] for an iPhone’s Touch ID, multiple readings would be needed to collect a complete initial record. Our research has confirmed that a combination of pictures like this would evoke brain wave readings that are unique to a particular person, and consistent from one login attempt to another.

Later, to login or gain access to a building or secure room, the person would put on the hat and watch the sequence of images. A computer system would compare their brain waves at that moment to what had been stored initially – and either grant access or deny it, depending on the results. It would take about five seconds, not much longer than entering a password or typing a PIN into a number keypad.

After a hack

Brain passwords’ real advantage comes into play after the almost inevitable hack of a login database. If a hacker breaks into the system storing the biometric templates or uses electronics to counterfeit a person’s brain signals, that information is no longer useful for security. A person can’t change their face or their fingerprints – but they can change their brain password.

It’s easy enough to authenticate a person’s identity another way, and have them set a new password by looking at three new images – maybe this time with a photo of a dog, a drawing of George Washington and a Gandhi quote. Because they’re different images from the initial password, the brainwave patterns would be different too. Our research has found that the new brain password would be very hard for attackers to figure out[12], even if they tried to use the old brainwave readings as an aid.

Brain passwords are endlessly resettable, because there are so many possible photos and a vast array of combinations that can be made from those images. There’s no way to run out of these biometric-enhanced security measures.

Secure – and safe

As researchers, we are aware that it could be worrying or even creepy for an employer or internet service to use authentication that reads people’s brain activity. Part of our research involved figuring out how to take only the minimum amount of readings to ensure reliable results – and proper security – without needing so many measurements that a person might feel violated or concerned that a computer was trying to read their mind.

We initially tried using 32 sensors all over a person’s head, and found the results were reliable. Then we progressively reduced the number of sensors to see how many were really needed – and found that we could get clear and secure results with just three properly located sensors.

Three electrodes high on the back of a user’s head are enough to detect a brain password.

Wenyao Xu et al., CC BY-ND[13]

Three electrodes high on the back of a user’s head are enough to detect a brain password.

Wenyao Xu et al., CC BY-ND[13]

This means our sensor device is so small that it can fit invisibly inside a hat or a virtual-reality headset. That opens the door for many potential uses. A person wearing smart headwear, for example, could easily unlock doors or computers with brain passwords. Our method could also make cars harder to steal – before starting up, the driver would have to put on a hat and look at a few images displayed on a dashboard screen.

Other avenues are opening as new technologies emerge. The Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba recently unveiled a system for using virtual reality to shop[14] for items – including making purchases online right in the VR environment. If the payment information is stored in the VR headset, anyone who uses it, or steals it, will be able to buy anything that’s available. A headset that reads its user’s brainwaves would make purchases, logins or physical access to sensitive areas much more secure.

References

- ^ relatively easily hacked (time.com)

- ^ fingerprints of 5.6 million U.S. federal employees (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Our (scholar.google.com)

- ^ team (scholar.google.com)

- ^ working with collaborators (www.eurekalert.org)

- ^ other institutions (doi.org)

- ^ her brain responds (www.encyclopedia.com)

- ^ every person’s brain responds differently (doi.org)

- ^ brain password (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ registering a fingerprint (www.macworld.co.uk)

- ^ very hard for attackers to figure out (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ using virtual reality to shop (news.vice.com)

Authors: Wenyao Xu, Assistant Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

Read more http://theconversation.com/my-thoughts-are-my-password-because-my-brain-reactions-are-unique-98691