IRS is using $60B funding boost to ramp up use of technology to collect taxes − not just hiring more enforcement agents

- Written by Erica Neuman, Assistant Professor of Accounting, University of Dayton

The Internal Revenue Service is getting a funding boost thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act[1], which President Joe Biden signed into law in 2022.

That legislative package originally included about US$80 billion to expand the tax collection agency’s budget over the next 10 years. Congress and the White House have since agreed to pare this total by about $20 billion[2], but $60 billion is still a big chunk of change for an agency that until recently had about $14 billion in annual funding[3].

I’m a tax researcher[4] who studies how the IRS uses technology[5] and how taxpayers respond to the agency’s growing reliance on it. While the number of IRS enforcement personnel will surely grow as a result of additional funding, I think that the agency can get more mileage out of emphasizing technological improvements.

Making enforcement more efficient

The IRS plans to use most of these new funds to step up enforcement and improve customer service[7] for taxpayers.

There’s been plenty of conjecture[8] about what the added enforcement will look like and no shortage of fearmongering[9] about the tens of thousands of new agents the IRS might hire[10].

Often left out of this discussion is the fact that the agency’s staffing was cut by 22% between 2010 and 2021[11]. Much of the agency’s hiring spree will replace these labor shortages rather than fill new posts. Further, the IRS expects over 50,000 of its employees to retire within five years[12].

The agency aims to hire 20,000 people over the next two years[13], of which one-third will work in enforcement.

But IRS Commissioner Daniel Werfel has indicated that better enforcement won’t just rely on more tax agents and auditors. He released a plan in early 2023 promising[14] that “technology and data advances will allow us to focus enforcement on taxpayers trying to avoid taxes, rather than taxpayers trying to pay what they owe.”

And U.S. Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo[15] has said that “the IRS is going to hire more data scientists than they ever have for enforcement purposes,” with the goal of using data analytics in audits.

At least initially, the agency was aiming to increase its spending on enforcement by 69%[16], from about $6.6 billion in 2022 to $11 billion in annual spending projected through 2031[17].

Technology, including the electronic filing of tax returns and a growing portfolio of online tools, transfer work from agents to computers. Online tools include the IRS’ digital scanning program[18], which expedites the processing of the roughly 1 in 5 federal tax returns that weren’t filed electronically in 2022[19].

Werfel says[20] the IRS workforce is becoming more efficient by ramping up its reliance on technology to provide services for taxpayers[21] and spot tax cheats[22].

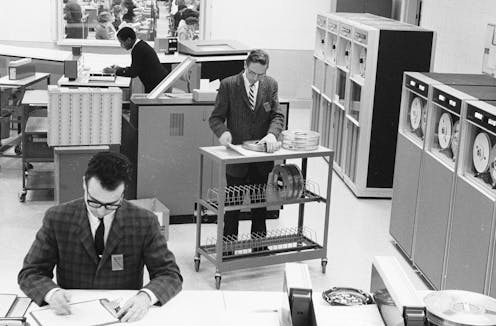

The IRS has tapped one form of data analytics or another to select people and companies to audit since the late 1960s[23]. As early as 1986, it had researched ways to use artificial intelligence[24] to improve how it selects its auditing targets.

At the same time, outdated technology is hampering the Internal Revenue Service’s effectiveness. It relies on a 60-year-old computer system[25] to maintain and process data. That undercuts its technological agility and customer service[26].

3 sources of data

When the IRS collects better data, its ability to use data analytics to make predictions about noncompliance[28] improves.

Beyond data reported on tax forms themselves, like 1099s, the IRS has three main sources of data it assesses to learn more about taxpayers.

1. Past tax returns

The IRS’s National Research Program collects data to support what it calls “strategic decisions[29]” to better enforce compliance.

The program first relies on its vast stores of taxpayer data, including prior audit results[30], to develop an expectation of what a given tax return may include, like a tuition tax credit for a taxpayer with a history of claiming the child tax credit. Filed returns are compared against those standards to identify potential outliers. Outliers aren’t necessarily dodging taxes or misrepresenting their tax liabilities, but big departures from the norms can indicate a higher likelihood of mistakes or evasion.

2. Publicly available data

The IRS relies on publicly available data associated with each tax return when it’s building a case[31] for an audit.

The data, which is available to anyone who wants to find it, has increased tremendously[32] with the rise of social media and the growing role of the internet for commerce and advertising. A social media presence can alert the IRS to a business with potential income in a way that the agency could not have identified before the internet emerged.

This includes methods that might surprise you.

As far back as 2010, for example, IRS training materials instructed agents to use a band’s social networking sites to compare musicians’ reported income with their likely income from their past performances[33]. IRS training materials instruct agents to predict musicians’ gig income based on the number of shows a band advertises through its social media posts.

People make all sorts of financial information public today, including their side hustles and Venmo ledgers. The IRS can access and use this data like anyone else.

3. Third-party data

The IRS can also buy data.

For example, a 2020 government contract with the company Chainalysis is described, perhaps clumsily, as a contract for “pilot IRS cryptocurrency tracing[34].” This type of contract gives the IRS information related to otherwise untraceable income sources so that agents can detect underreporting.

What has changed in recent years is the volume of data it can access, which has skyrocketed[35].

Sometimes, widespread underreporting results in legislation which requires third parties to report income information to the IRS, rather than requiring the agency seek it out.

Recent legislation includes requiring third-party payment agencies like Venmo, PayPal and Uber to issue a 1099 tax form to anyone making over $600 on the app in one year[36]. These 1099s are issued to taxpayers – and the IRS.

Similar legislation was recently proposed for cryptocurrency transactions[37].

What might change

What does this increase in IRS spending on technology mean for taxpayers?

When the IRS detailed how it wanted to use the new funds[38] in April 2023, it emphasized improving taxpayers’ experiences and increasing compliance. By using chatbots to respond to taxpayer questions[39], providing online portals for real-time processing, and letting taxpayers respond to notices online[40], the IRS could substantially decrease the time taxpayers spend corresponding with the agency or waiting on hold while attempting to speak to a staffer.

Technology-boosted enforcement could help the agency collect more revenue to fund government programs[41].

And the agency also hopes to use data to make paying taxes less onerous for the majority of Americans who follow the rules.

For example, when a taxpayer has a child or experiences another kind of life change that will change their tax status, the IRS wants to gain the ability to proactively notify people about the consequences – whether it’s paying more, owing less or getting a new tax credit[42].

Most people want to pay what they owe, no more and no less. I believe the IRS intends to make good use of its new funding to help people do just that.

References

- ^ Inflation Reduction Act (www.irs.gov)

- ^ pare this total by about $20 billion (www.politico.com)

- ^ about $14 billion in annual funding (www.irs.gov)

- ^ tax researcher (scholar.google.com)

- ^ IRS uses technology (doi.org)

- ^ Alex Wong/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ enforcement and improve customer service (crsreports.congress.gov)

- ^ plenty of conjecture (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ no shortage of fearmongering (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ new agents the IRS might hire (apnews.com)

- ^ was cut by 22% between 2010 and 2021 (www.cbpp.org)

- ^ over 50,000 of its employees to retire within five years (www.reuters.com)

- ^ 20,000 people over the next two years (www.reuters.com)

- ^ released a plan in early 2023 promising (www.irs.gov)

- ^ U.S. Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo (www.reuters.com)

- ^ increase its spending on enforcement by 69% (taxfoundation.org)

- ^ $6.6 billion in 2022 to $11 billion in annual spending projected through 2031 (crsreports.congress.gov)

- ^ the IRS’ digital scanning program (www.irs.gov)

- ^ returns that weren’t filed electronically in 2022 (www.irs.gov)

- ^ Werfel says (www.irs.gov)

- ^ services for taxpayers (www.irs.gov)

- ^ spot tax cheats (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ since the late 1960s (www.gao.gov)

- ^ use artificial intelligence (www.thefreelibrary.com)

- ^ relies on a 60-year-old computer system (www.gao.gov)

- ^ customer service (www.cnn.com)

- ^ Robert Barnes/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ data analytics to make predictions about noncompliance (www.tx.cpa)

- ^ strategic decisions (www.irs.gov)

- ^ including prior audit results (www.irs.gov)

- ^ it’s building a case (www.irs.gov)

- ^ increased tremendously (www.gao.gov)

- ^ income from their past performances (www.computerworld.com)

- ^ pilot IRS cryptocurrency tracing (www.usaspending.gov)

- ^ which has skyrocketed (scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu)

- ^ anyone making over $600 on the app in one year (theconversation.com)

- ^ cryptocurrency transactions (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ IRS detailed how it wanted to use the new funds (www.irs.gov)

- ^ chatbots to respond to taxpayer questions (www.irs.gov)

- ^ respond to notices online (home.treasury.gov)

- ^ collect more revenue to fund government programs (www.irs.gov)

- ^ paying more, owing less or getting a new tax credit (www.irs.gov)

Authors: Erica Neuman, Assistant Professor of Accounting, University of Dayton