Marburg virus outbreaks are increasing in frequency and geographic spread – three virologists explain

- Written by Adam Hume, Research Assistant Professor of Microbiology, Boston University

The World Health Organization confirmed an outbreak of the deadly Marburg virus disease[1] in the central African country of Equatorial Guinea on Feb. 13, 2023. To date, there have been 11 deaths suspected to be caused by the virus[2], with one case confirmed. Authorities are currently monitoring 48 contacts, four of whom have developed symptoms and three of whom are hospitalized as of publication. The WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are assisting Equatorial Guinea in its efforts to stop the spread of the outbreak.

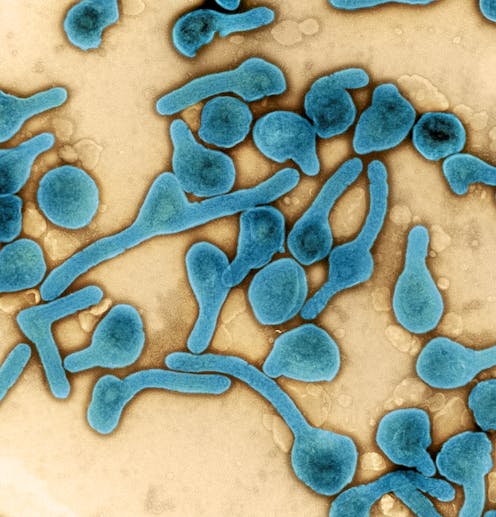

Marburg virus[4] and the closely related[5] Ebola virus belong to the filovirus family[6] and are structurally[7] similar[8]. Both viruses cause severe disease and death in people, with fatality rates ranging from 22% to 90% depending on[9] the outbreak[10]. Patients infected by these viruses exhibit a wide range of similar symptoms[11], including fever, body aches, severe gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea and vomiting, lethargy and sometimes bleeding.

We are virologists[12] who[13] study[14] Marburg, Ebola and related viruses. Our laboratory[15] has a long-standing interest in researching the underlying mechanisms of how these viruses cause disease in people. Learning more about how Marburg virus is transmitted from animals to humans and how it spreads between people is essential to preventing and limiting future outbreaks.

Marburg virus disease

Marburg virus spreads between people by close contact only after they show symptoms. It is transmitted through infected body fluids[16] such as blood, and is not airborne. Contact tracing is a potent tool to combat outbreaks. The incubation time, or time between infection and the onset of symptoms, ranges from two to 21 days and typically falls between five and 10 days. This means that contacts must be observed for extended periods for potential symptoms.

Marburg virus cannot be detected before patients are symptomatic[17]. One major cause of the spread of Marbug virus disease is postmortem transmission[18] due to traditional burial procedures, where family and friends typically have direct skin-to-skin contact with people who have died from the disease.

There are currently no approved treatments[19] or vaccines[20] against Marburg virus disease. The most advanced vaccine candidates in development use strategies that have been shown[21] to be effective[22] at protecting against[23] Ebola virus disease[24].

Without effective treatments or vaccines, Marburg virus outbreak control[25] primarily relies on contact tracing, sample testing, patient contact monitoring, quarantines and attempts to limit or modify high-risk activities such as traditional funeral practices[26].

What causes Marburg virus outbreaks?

Marburg virus outbreaks have an unusual history.

The first recorded outbreak[27] of Marburg virus disease occurred in Europe. In 1967, laboratory workers in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany, as well as in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia) were infected with a previously unknown pathogen[28] after handling infected monkeys that had been imported from Uganda. This outbreak led to the discovery of the Marburg virus[29].

Identifying the virus took only three months, which, at the time, was incredibly fast considering the available research tools. Despite receiving intensive care, seven of the 32 patients died[30]. This case fatality rate of 22% was relatively low compared to subsequent Marburg virus outbreaks in Africa, which have had a cumulative case fatality rate of 86%[31]. It remains unclear if these differences in lethality are due to variability in patient care options or other factors such as distinct viral strains.

Subsequent Marburg virus disease outbreaks occurred in Uganda and Kenya, as well as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola in Central Africa. In addition to the current outbreak in Equatorial Guinea, recent Marburg virus cases in the West African countries of Guinea in 2021 and Ghana in 2022 highlight that the Marburg virus is not confined to Central Africa[32].

Strong evidence shows that the Egyptian fruit bat[33], a natural animal reservoir of Marburg virus, might play an important role in spreading the virus to people. The location of all Marburg virus outbreaks coincides with the natural range of these bats[34]. The large area of Marburg virus outbreaks is unsurprising, given the ecology of the virus[35]. However, the mechanisms of zoonotic, or animal-to-human, spread of Marburg virus still remain poorly understood.

The origin of a number of Marburg virus disease outbreaks is closely linked to human activity in caves where Egyptian fruit bats roost. More than half of the cases in a 1998 outbreak in the northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo were among gold miners who had worked in Goroumbwa Mine[37]. Intriguingly, the end of the nearly two-year outbreak coincided with the flooding of the cave and the disappearance of the bats in the same month.

Similarly, in 2007, four men who worked in a gold and lead mine[38] in Uganda where thousands of bats were known to roost became infected with Marburg virus. In 2008, two tourists were infected with the virus after visiting Python Cave[39] in the Maramagambo Forest in Uganda. Both developed severe symptoms after returning to their home countries – the woman from the Netherlands died[40] and the woman from the United States survived[41].

The geographic range of Egyptian fruit bats[42] extends to large portions of sub-Saharan Africa and the Nile River Delta, as well as portions of the Middle East. There is potential for zoonotic spillover events[43], to occur in any of these regions.

More frequent outbreaks

Although Marburg virus disease outbreaks have historically been sporadic, their frequency has been increasing[44] in recent years.

The increasing emergence and reemergence of zoonotic viruses, including filoviruses (such as Ebola[45], Sudan[46] and Marburg[47] viruses), coronaviruses (which cause SARS[48], MERS[49] and COVID-19[50]), henipaviruses (such as Nipah[51] and Hendra[52] viruses) and Mpox[53] appear to be influenced by both human encroachment[54] on previously undisturbed animal habitats and alterations to wildlife habitat ranges due to climate change[55].

Most Marburg virus outbreaks have occurred in remote areas, which has helped to contain the spread of the disease. However, the large geographic distribution of Egyptian fruit bats that harbor the virus raises concerns that future Marburg virus disease outbreaks could happen in new locations and spread to more densely populated areas, as seen by the devastating Ebola virus outbreak in 2014 in West Africa[56], where over 11,300 people died[57].

References

- ^ outbreak of the deadly Marburg virus disease (www.who.int)

- ^ 11 deaths suspected to be caused by the virus (www.rfi.fr)

- ^ Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Marburg virus (doi.org)

- ^ closely related (doi.org)

- ^ filovirus family (doi.org)

- ^ structurally (doi.org)

- ^ similar (doi.org)

- ^ depending on (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ the outbreak (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ wide range of similar symptoms (doi.org)

- ^ virologists (scholar.google.com)

- ^ who (scholar.google.com)

- ^ study (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Our laboratory (www.bu.edu)

- ^ infected body fluids (doi.org)

- ^ cannot be detected before patients are symptomatic (doi.org)

- ^ postmortem transmission (doi.org)

- ^ treatments (doi.org)

- ^ vaccines (doi.org)

- ^ have been shown (doi.org)

- ^ to be effective (doi.org)

- ^ protecting against (doi.org)

- ^ Ebola virus disease (doi.org)

- ^ outbreak control (doi.org)

- ^ traditional funeral practices (doi.org)

- ^ first recorded outbreak (doi.org)

- ^ infected with a previously unknown pathogen (doi.org)

- ^ discovery of the Marburg virus (doi.org)

- ^ seven of the 32 patients died (doi.org)

- ^ cumulative case fatality rate of 86% (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ not confined to Central Africa (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Egyptian fruit bat (doi.org)

- ^ natural range of these bats (www.iucnredlist.org)

- ^ ecology of the virus (doi.org)

- ^ Bonnie Jo Mount/The Washington Post via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ gold miners who had worked in Goroumbwa Mine (doi.org)

- ^ worked in a gold and lead mine (doi.org)

- ^ Python Cave (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ woman from the Netherlands died (doi.org)

- ^ woman from the United States survived (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ geographic range of Egyptian fruit bats (www.iucnredlist.org)

- ^ zoonotic spillover events (theconversation.com)

- ^ frequency has been increasing (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Ebola (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Sudan (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Marburg (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ SARS (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ MERS (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ COVID-19 (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Nipah (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Hendra (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ Mpox (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ human encroachment (doi.org)

- ^ due to climate change (doi.org)

- ^ Ebola virus outbreak in 2014 in West Africa (doi.org)

- ^ over 11,300 people died (www.cdc.gov)

Authors: Adam Hume, Research Assistant Professor of Microbiology, Boston University