Sex education lessons from Mississippi and Nigeria

- Written by Rachel Sullivan Robinson, Associate Professor, American University School of International Service

Nigeria and Mississippi are a world apart physically, but the rural American state and the African country have much in common when it comes to the obstacles they had to overcome to implement sex education in their schools.

Three lessons about overcoming these obstacles come out of research[1] that several colleagues and I conducted[2] on how sex education came to be in Nigeria[3] and Mississippi[4].

The lessons are particularly relevant for similarly religious and conservative places where people often worry – as they do throughout the world – that teaching young people about contraception and condoms will make them more likely to have sex[5]. The lessons also come as the United States itself is embroiled in an ongoing controversy[6] over whether to fund comprehensive sex education or emphasize the abstinence-only approach. More than half of states in the U.S. require that sex education stress abstinence[7]. Comprehensive sex education in African and other developing countries is more the exception than the rule[8].

Sex education does not cause more sex

Although people often worry that sex education will lead to promiscuity, the evidence doesn’t support the notion that sex education makes young people more sexually active – at least not in the United States or in Africa[9].

Despite the fact that comprehensive sex education has been shown[10] to protect adolescent health, it can be difficult to dispel fears[11] that it will corrupt young people and reduce parental and religious authority. This is particularly so in socially conservative places.

Different approaches

Not all sex education is created equal. The gold standard from a health perspective is referred to as “comprehensive” sex education. The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States defines this[12] as “age-appropriate, medically accurate information on a broad set of topics related to sexuality including human development, relationships, decision making, abstinence, contraception and disease prevention.”

Comprehensive sex education has been shown[13] to delay the age of the first sexual encounter, increase use of condoms and contraception, and reduce rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.

Comprehensive sex education is very different than abstinence-only education. Abstinence-only education, in best-case scenarios, teaches the same life skills but without reference to contraception. Most of the research on abstinence-only education[14] finds it to be less effective than comprehensive sex education in delaying the first sexual encounter, increasing condom use or reducing the number of sexual partners.

Same problems, different places

Why compare experiences of sex education in a mid-sized U.S. state to those in the most populous country in Africa? It turns out Mississippi and Nigeria share some key similarities.

Mississippi is among the U.S. states with the highest teen pregnancy rates[15]. In Nigeria, almost a quarter of women have begun childbearing by age 19[16].

Mississippi[17] and Nigeria[18] are also highly religious and rural. Both also have underfunded education[19] and health[20] systems. Despite these conditions, Nigeria mandated the teaching of sex education in 2001. However, implementation didn’t begin in earnest until 2011 with the support of a grant from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria[21]. By that time, the curriculum had shifted from comprehensive to abstinence-only. Mississippi required school districts to implement sex education by 2012 but under similarly restrictive conditions.

The jury is still out on the effects of sex education in Mississippi and Nigeria. However, some positive evidence exists for both places. For instance, in Mississippi[22], more than three-quarters of instructors surveyed in 2015 believed that sex education was promoting healthy relationships. And in four states in Nigeria[23], researchers concluded that the curriculum increased students’ confidence to refuse unwanted sex.

Three lessons about overcoming controversies around sex education emerged from my research in Nigeria and Mississippi.

Local organizations are crucial

First, strong, local organizations are necessary to promote sex education. In both places, homegrown organizations lobbied, connected people and provided legitimacy to the idea of teaching sex education. Crucially, these organizations were supported by funding from private donors or the federal government.

The Women’s Foundation of Mississippi[24] funded and published a report showing the cost of teen pregnancy to taxpayers. The Center for Mississippi Health Policy[25] supported a 2011 survey that showed parents overwhelmingly supported sex education. Mississippi First[26] trains teachers on comprehensive sex education. It also helps channel funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to school districts that teach evidence-based sex education curricula.

In Nigeria, Action Health Incorporated[27] led a coalition of NGOs, professional associations, donor organizations and federal ministries to form a task force. The task force helped write guidelines[28] for sex education in 1996 that led to the adoption of curriculum in 2001. The Association for Reproductive and Family Health[29] led the nationwide implementation of the curriculum with support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

A cure for societal ills

Second, to promote sex education, these organizations presented sex education as a solution to social problems. In Mississippi, the problem was identified as the taxpayer cost of teen pregnancy. In Nigeria, it was the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The Mississippi Economic Policy Center[30] found in 2011 that the county-by-county cost of teen pregnancy to taxpayers was an estimated US$155 million[31] in 2009. This cost was due to lost tax revenue, medical care, public assistance, foster care and other expenses. In Nigeria, data in the late 1990s[32] indicated that 2 to 4 million Nigerians – approximately 5 percent of the adult population – were HIV positive. Many feared that Nigeria’s epidemic would come to resemble those in southern Africa[33]. Sex education, which promised to reduce teen pregnancy and quell HIV transmission, served as a solution to these problems.

Compromise is necessary

Third, those promoting sex education were strategic. Proponents reached out to religious leaders, school officials and parents in order to allay their fears about teaching their kids about sex. And they made sure to stress that sex education was about health and life skills.

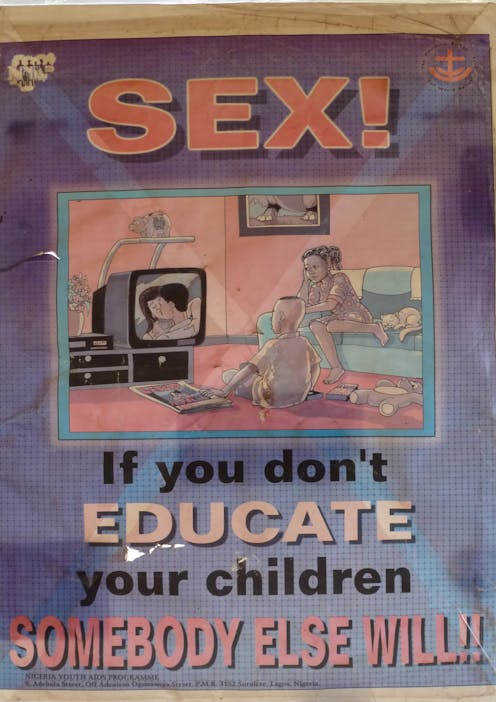

Still, in Mississippi and Nigeria, supporters had to compromise about the content of the curriculum. They agreed to change words and remove controversial sections. Consequently, in Mississippi, school districts can choose to teach abstinence-only curriculum. Condom demonstrations are not permitted, and the curriculum must be taught in gender-segregated classrooms. In Nigeria, the name of the curriculum was changed from the “National Comprehensive Sexuality Education Curriculum” to the more euphemistic “Family Life and HIV Education.” In addition, several more conservative states removed the words “sex” and “breast,” as well as images that show sexually transmitted infections.

While there is no universal way to ensure access to sex education, the experiences in Nigeria and Mississippi show that it can be done – even in places that are most resistant to the idea.

References

- ^ research (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ I conducted (scholar.google.com)

- ^ Nigeria (rdcu.be)

- ^ Mississippi (billstatus.ls.state.ms.us)

- ^ more likely to have sex (press.princeton.edu)

- ^ embroiled in an ongoing controversy (www.cnn.com)

- ^ require that sex education stress abstinence (www.guttmacher.org)

- ^ more the exception than the rule (unesdoc.unesco.org)

- ^ in the United States or in Africa (www.jahonline.org)

- ^ shown (link.springer.com)

- ^ it can be difficult to dispel fears (www.foreignaffairs.com)

- ^ defines this (www.siecus.org)

- ^ shown (link.springer.com)

- ^ research on abstinence-only education (www.guttmacher.org)

- ^ highest teen pregnancy rates (www.cdc.gov)

- ^ almost a quarter of women have begun childbearing by age 19 (dhsprogram.com)

- ^ Mississippi (news.gallup.com)

- ^ Nigeria (www.telegraph.co.uk)

- ^ underfunded education (www.edweek.org)

- ^ health (wdi.worldbank.org)

- ^ grant from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (www.theglobalfund.org)

- ^ Mississippi (www.mshealthpolicy.com)

- ^ Nigeria (iwhc.org)

- ^ Women’s Foundation of Mississippi (www.womensfoundationms.org)

- ^ Center for Mississippi Health Policy (www.mshealthpolicy.com)

- ^ Mississippi First (www.mississippifirst.org)

- ^ Action Health Incorporated (www.actionhealthinc.org)

- ^ guidelines (www.siecus.org)

- ^ Association for Reproductive and Family Health (arfh-ng.org)

- ^ Mississippi Economic Policy Center (hopepolicy.org)

- ^ estimated US$155 million (www.issuelab.org)

- ^ data in the late 1990s (www.unaids.org)

- ^ those in southern Africa (ourworldindata.org)

Authors: Rachel Sullivan Robinson, Associate Professor, American University School of International Service

Read more http://theconversation.com/sex-education-lessons-from-mississippi-and-nigeria-96334