Nina Otero-Warren – Latina champion of women's voting rights and education in New Mexico – will soon grace US quarters

- Written by Anna María Nogar, Professor of Hispanic Southwest Studies, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of New Mexico

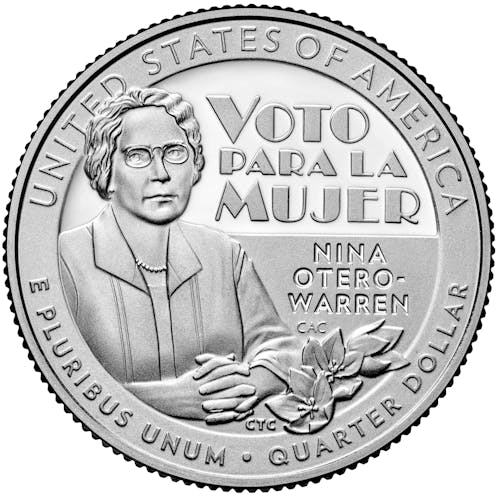

Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren was an activist who fought for women’s voting rights during the 20th century. She was the first Latina to run for Congress and the first Latina superintendent of the Santa Fe public schools. She is one of several women whose images are being featured on the U.S. quarter in 2022[1]. The quarter in her honor is set to be released on Aug. 15, 2022[2]. Here, Anna María Nogar[3], professor of Hispanic Southwest studies at the University of New Mexico, writes about Otero-Warren’s work and legacy.

1. How did Otero-Warren contribute to women’s political rights?

Otero-Warren tirelessly advocated in Spanish and English for New Mexico to ratify the 19th Amendment[4] to the U.S. Constitution, which gave women the right to vote. In order for a constitutional amendment to take effect, it must be ratified by three-fourths of all states[5].

In New Mexico, Otero-Warren implemented strategies advanced by the Congressional Union[6], a national organization established in 1913 to advocate for women’s right to vote. She lobbied state leaders to vote in favor of ratification. Since the first language of the vast majority of New Mexicans was Spanish[7], her bilingualism helped her work with opinion leaders across communities to keep suffrage and women’s rights front and center.

She was accompanied in her fight for women’s rights by fellow nuevomexicanas – as Otero-Warren and her colleagues referred to themselves – Soledad Chávez Chacón[8] and folklorist Aurora Lucero[9]. Together, these women worked to pave the way for future female leadership in the state. In 1922, for example, Chacón became the first Latina in the country to be elected to statewide office, serving as New Mexico’s secretary of state.

In the early 1920s, Otero-Warren served as a chairwoman of the State Federation of Women’s Clubs. As chairwoman, she worked toward progressive goals. Part of her work included persuading lawmakers to raise the age of consent from 16 to 18. She also worked to advance an act to provide for the care of dependent and neglected children.

In 1921, women were guaranteed the right to run for office in New Mexico by passage of an amendment to the state constitution. In 1922, Otero-Warren became the first Latina in the country to vie for a congressional seat, running as a Republican. Despite losing to Democrat James Hinkle by 9 percentage points, her ability to speak directly to nuevomexicanos made her candidacy highly visible.

Her policy platform was published in Spanish-language newspapers like La Revista de Taos. This ensured that the Spanish speakers would understand her support of farmers, ranchers, educators, children and families. She was devoted to nuevomexicanos and said she would consider it “un alto honor y una oportunidad para el servicio” – “a high honor and opportunity to serve” if elected to Congress.

2. What did she do for education in New Mexico?

As the first Latina superintendent of the public schools of Santa Fe, a position she held from 1917 to 1929, Otero-Warren promoted education in Santa Fe and its surrounding rural areas. She also pushed for bilingual and Native education in schools and communities. From 1848 on, federal politicians had tried to eliminate Spanish in educational settings and for official purposes in New Mexico as a condition for its statehood[11]. In 1912, when New Mexico became a state, its constitution ultimately retained Spanish as an official state language.

Otero-Warren balanced the needs and desires of Spanish-speaking nuevomexicanos with federal-level expectations for English usage in public schools. Otero-Warren and others lobbied state leadership to ensure Spanish was retained as a public language so that Spanish speakers were not impeded from employment and appointment to federal and state-funded positions. In doing so, they maintained social and political enfranchisement for nuevomexicanos.

She also pushed to improve the sanitary conditions and children’s living quarters at the Santa Fe Indian School, a boarding school for Native children established by the federal government in 1890. Otero-Warren was an inspector of Indian Services for the Department of the Interior from 1922 to 1924 and was the first woman to occupy that role.

Otero-Warren served as state supervisor of literacy classes in 1937 under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration. In this role, she designed a teaching curriculum for Spanish-speaking adults to learn English in their communities while retaining their Spanish literacy.

Later in her life, she wrote about Indo-Hispano life in New Mexico. Her book “Old Spain in Our Southwest[12]” told the stories of New Mexicans in their own words. This ran counter to the depiction of New Mexico’s people in many English-language publications as primitive, uncultured or unlettered[13].

In her book, Otero-Warren made New Mexican culture intelligible to outsiders. She did this by documenting community practices such as Holy Week celebrations or rituals for marriage, recording bilingual expressions such as “Ni con jabón de la Puebla” to say something so dirty that not even fine soap could clean it, and recalling shared values and educational practices that predated American colonization.

How is she remembered in New Mexico today?

Otero-Warren is commemorated as an advocate for voting rights for women on a mural[14] in downtown Albuquerque. It is a daily visual reminder in the heart of the city of her vital political interventions. The New Mexico Historic Women Marker Initiative, begun in 2007, dedicated a historical marker[15] to Otero-Warren in her birthplace of La Costancia, connecting her to community and home.

The 2021 publication of El feliz ingenio neomexicano[16], a bilingual collection of poems by journalist Felipe M. Chacón, brought Otero-Warren’s active political life back to the fore. His 1922 poem supporting her campaign for Congress noted that her election would reflect New Mexico’s progressivism, advanced by its Spanish-speaking citizenry. His words reflect how she is still known today:

“Cubrirá Nuevo México de Gloria / Poniendo una mujer en el Congreso … Un brindis de alegría / Placer del progresivo ciudadano.”

“New Mexico will be covered in glory / By sending a woman to Congress … A toast of joy / And gratitude from its progressive citizens.”

References

- ^ the U.S. quarter in 2022 (www.usmint.gov)

- ^ set to be released on Aug. 15, 2022 (www.coinworld.com)

- ^ Anna María Nogar (theconversation.com)

- ^ 19th Amendment (www.archives.gov)

- ^ ratified by three-fourths of all states (www.ncsl.org)

- ^ Congressional Union (spartacus-educational.com)

- ^ was Spanish (www.ucpress.edu)

- ^ Soledad Chávez Chacón (digitalrepository.unm.edu)

- ^ Aurora Lucero (digitalrepository.unm.edu)

- ^ Library of Congress/Emcee/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ as a condition for its statehood (www.worldcat.org)

- ^ Old Spain in Our Southwest (www.sunstonepress.com)

- ^ primitive, uncultured or unlettered (unmpress.com)

- ^ mural (www.indianz.com)

- ^ historical marker (www.nmhistoricpreservation.org)

- ^ El feliz ingenio neomexicano (unmpress.com)

Authors: Anna María Nogar, Professor of Hispanic Southwest Studies, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of New Mexico