Schadenfreude over Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis was more about cosmic justice than joy in another’s pain

- Written by Lee M. Pierce, Assistant Professor Rhetoric and Communication, State University of New York, College at Geneseo

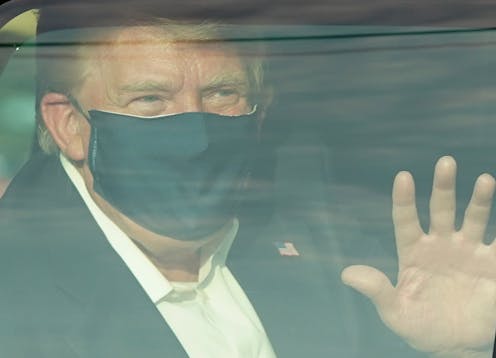

After President Donald Trump announced his COVID-19 diagnosis, Merriam-Webster Dictionary reported a 30,000% increase[1] in searches for the word “schadenfreude.”

The German word, which is often translated[2] as “harm joy,” or “joy in someone else’s pain,” instantly became a subject of debate.

GQ and Newsweek[3], along with Stephen Colbert[4] of “The Late Show,” wondered whether schadenfreude was a morally defensible response to the president’s diagnosis.

MSNBC host Rachel Maddow said absolutely not[5]. Harvard professor Laurence Tribe went further[6], writing that this was no time for “cruelty, schadenfreude, or any other form of small-mindedness.”

I agree that cruelty is small-minded and indefensible. But as a scholar of rhetoric[7], I have a difficult time looping schadenfreude in with small-minded cruelty.

One of the issues is that the common English translation of schadenfreude – “harm joy” – fails to adequately capture the nuances of the term, and misses what’s most poignant about it.

The realization of divine symmetry

Perhaps the confusion comes from the social sciences. Recent studies of schadenfreude have oversimplified it as the “darker side” of human emotion[8].

But at its best, schadenfreude is actually a recognition of ironic justice.

Irony is frequently misused[9] in American political discourse as simply not meaning what you said. However, irony is a very specific rhetorical device by which something returns as its opposite. “A returns as not A” is the classic formulation.

In the case of Trump, he downplayed the seriousness of COVID-19[10] and ended up being diagnosed with a serious case of the virus himself. A returned as not A.

That is classic irony. Then there’s the justice element.

Trump didn’t simply downplay it in a vacuum. He was in charge of the federal government’s response to a pandemic that has devastated thousands of families across the country. To them, COVID-19 has been deadly serious[11]. So in this case, the irony doubles as a form of justice.

By justice, I don’t mean rule of law or a system of punishment. I mean justice in its older sense of divine symmetry[12]. The roots of the word “justice” have several potential origins, including the Latin ūstitia, loosely translated as “equity,” and the pre-Latin word “jowos,” loosely translated as “sacred formula.”

Schadenfreude is about appreciating that sacred formula at work in a secular world. Maybe you observe with satisfaction as the person who mocked your weight in high school asks for diet advice on Facebook. Or maybe you look on contentedly as your grandchild gives your child the same grief over broccoli that your child gave you.

Is that small-minded cruelty? Or are you appreciating the cosmic irony by which a perceived wrong has been righted?

An emotional middle ground

Appreciation is not simply another word for happiness or glee. Those are emotions that feel good, the way cuddles with loved ones and delicious desserts feel good.

A sense of appreciation or satisfaction after witnessing poetic justice at work[13] is different, and schadenfreude is a milder experience that involves satisfaction.

To Sigmund Freud, satisfaction was best explained by the word “befriedigung[14],” which means “ceasing displeasure.”

Ceasing displeasure is not the same thing as experiencing pleasure. It’s about bringing things back into balance. “Befriedigung” occupies an emotional middle ground that can be difficult to grasp in a culture that prefers extreme, binary emotions[15].

The president’s tendency toward hyperbolic and grandiose language[16] is symptomatic of the country’s cultural preference for the huge emotions[17], such as anger, guilt, happiness and pleasure. Schadenfreude is an emotional chisel in an internet and media landscape that prefers blunt rhetorical instruments.

When schadenfreude veers into hopelessness

That said, schadenfreude can certainly go too far.

Just a few decades before Freud, another influential German thinker, Friedrich Nietzsche, argued that schadenfreude[18], pushed to its limits, becomes another word: “ressentiment.” In “On the Genealogy of Morality[19],” Nietzsche defined ressentiment as “slave morality,” a feeling of superiority derived from one’s own suffering.

Think of it like a sliding scale. On the far end is simple justice: Someone in power does the right thing, like your boss approving your vacation request after you’ve worked six months with no time off. But let’s suppose your boss says no to the request. And then no again two months later. And then no again two months after that. At that point, you might appreciate learning that your boss was denied a vacation request by headquarters. That’s schadenfreude. You might even point out this cosmic irony to your boss, hoping it will make a difference.

But when it doesn’t – and your boss continues treating you poorly – you might start reveling in your own victimhood. You take every chance you can to tell your co-workers that your boss is out to get you. That’s ressentiment.

Ressentiment takes hold once the possibility for justice is no longer on the horizon. Under those conditions, even the most poignant appreciations of irony cannot speak truth to power. In turn, an oppressed people would understandably take refuge in an extreme form of schadenfreude.

But in between justice and ressentiment is a rich, gray area where schadenfreude can serve a valuable political purpose[20]. If those in power won’t take responsibility for the injustices they have perpetuated – either knowingly or not – then it’s certainly OK for people to appreciate those moments when the chickens come home to roost[21].

References

- ^ reported a 30,000% increase (www.merriam-webster.com)

- ^ often translated (theconversation.com)

- ^ Newsweek (www.newsweek.com)

- ^ Stephen Colbert (www.vulture.com)

- ^ absolutely not (www.foxnews.com)

- ^ went further (twitter.com)

- ^ But as a scholar of rhetoric (scholar.google.com)

- ^ oversimplified it as the “darker side” of human emotion (www.sciencedaily.com)

- ^ Irony is frequently misused (theconversation.com)

- ^ downplayed the seriousness of COVID-19 (www.npr.org)

- ^ COVID-19 has been deadly serious (abcnews.go.com)

- ^ justice in its older sense of divine symmetry (www.jstor.org)

- ^ after witnessing poetic justice at work (doi.org)

- ^ befriedigung (www.cairn-int.info)

- ^ prefers extreme, binary emotions (www.routledge.com)

- ^ tendency toward hyperbolic and grandiose language (www.timesofisrael.com)

- ^ cultural preference for the huge emotions (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ argued that schadenfreude (www.jstor.org)

- ^ On the Genealogy of Morality (philosophy.ucsc.edu)

- ^ rich, gray area where schadenfreude can serve a valuable political purpose (books.google.com)

- ^ the chickens come home to roost (doi.org)

Authors: Lee M. Pierce, Assistant Professor Rhetoric and Communication, State University of New York, College at Geneseo