There's nothing unusual about early voting – it's been done since the founding of the republic

- Written by Terri Bimes, Associate Teaching Professor of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley

With voting in key states having begun more than six weeks before Election Day[1], early voting has emerged as a contentious issue. Observing that the country now has more of an election season than an election day, Attorney General Bill Barr lamented that “we’re losing the whole idea of what an election is[2].”

I’m a scholar of the presidency. And as many in this field know, early voting periods are not new to the 2020 election.

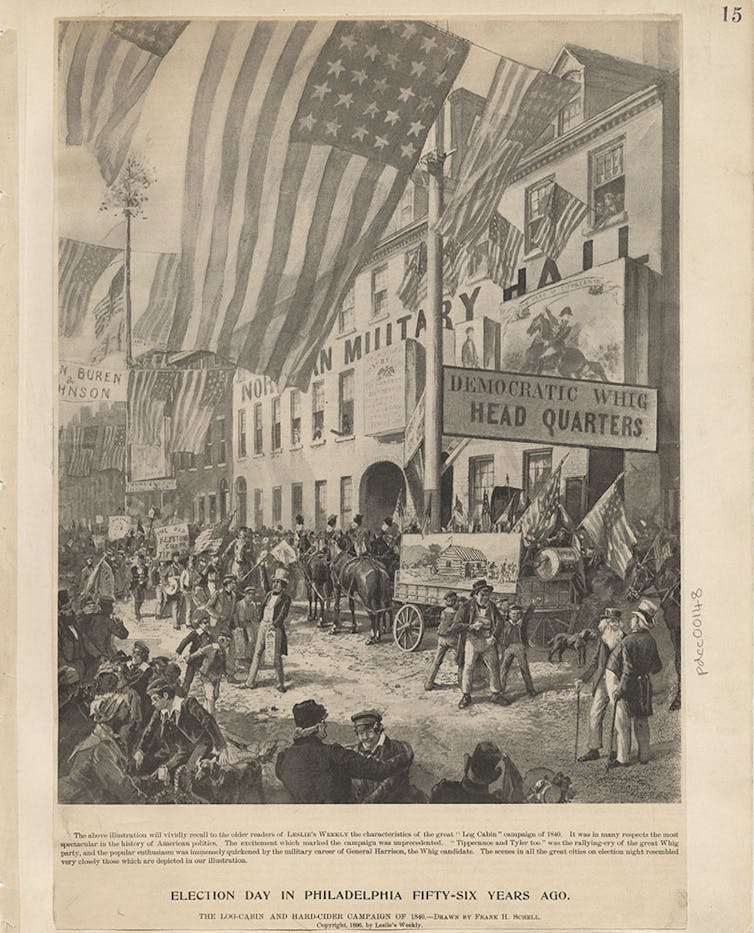

In 1840, Pennsylvania held its election on Friday, Oct. 30. At the time, most other states held their presidential elections on a Monday or Tuesday.

Artist, Frederic B. Schell/Free Library of Philadelphia[3]

In 1840, Pennsylvania held its election on Friday, Oct. 30. At the time, most other states held their presidential elections on a Monday or Tuesday.

Artist, Frederic B. Schell/Free Library of Philadelphia[3]

First presidential election took one month

There are many historical examples of an election period as opposed to an election day.

At the founding, there was no set national election day. The first presidential election[4] started on Dec. 15, 1788, and ended almost a month later, on Jan. 10, 1789.

In 1792, Congress passed a law[5] that permitted each state to choose presidential electors any time within a 34-day period before the first Wednesday in December. During this period, states determined what day to hold their presidential elections, resulting in a patchwork of election days. Most states had their election on a single day, but some had elections over the course of two days.

From 1789 to 1840[6], states gradually converged on early November as the time to hold their presidential elections, laying the groundwork for congressional adoption of a uniform presidential election day.

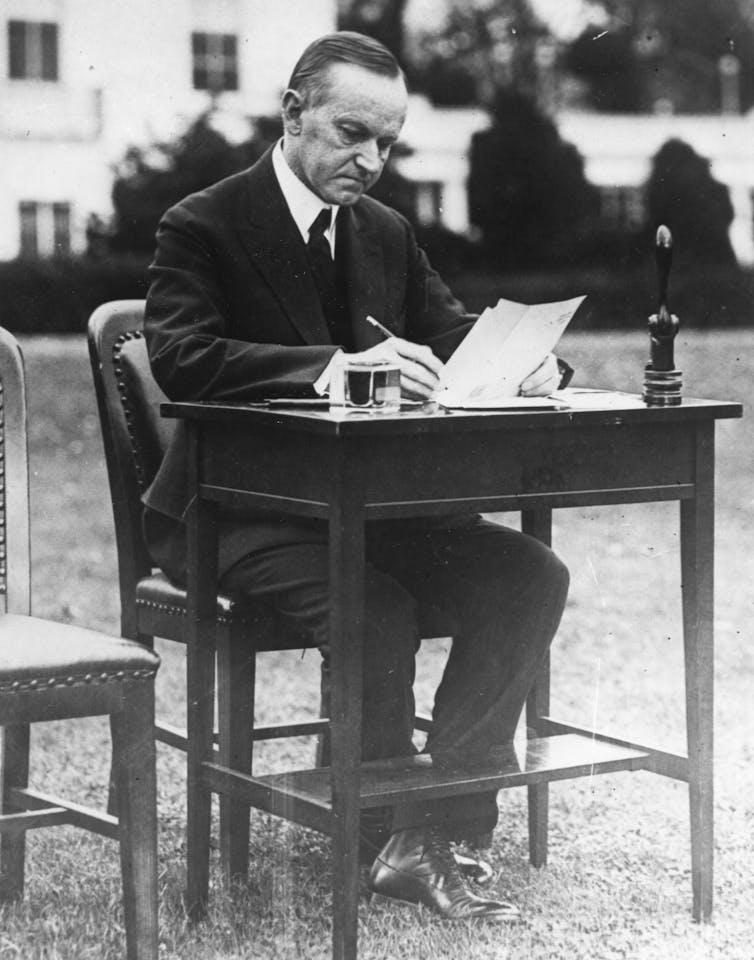

President Calvin Coolidge filling out his absentee ballot on Oct. 30, 1924. That year’s election was held on Nov. 4, and Coolidge won.

PhotoQuest/Getty Images[7]

President Calvin Coolidge filling out his absentee ballot on Oct. 30, 1924. That year’s election was held on Nov. 4, and Coolidge won.

PhotoQuest/Getty Images[7]

The 1840 presidential electoral season[8] began on Friday, Oct. 30, in Ohio and Pennsylvania and ended on Thursday, Nov. 12, in North Carolina, except for South Carolina, whose state Legislature still chose its electors.

Limiting voter fraud

It wasn’t until 1845 that Congress formally adopted a national election day[9] — the Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

With the invention of the telegraph, the rise of two-party competition across most states and record-breaking voter turnout, both parties had an interest in regulating elections and establishing a national election day.

In addition, parties were becoming more concerned about election fraud, especially the “the importation of voters from one State to another.”[10] Most of the discussion in Congress focused on which day election day should be, with the prevailing idea that it should be about 30 days before the meeting of the electors, and on a Tuesday, according to a story in The Boston Daily Globe in February of 1915.

The legislators chose Tuesday because most states already held their elections on Monday or Tuesday, and they thought it was generally a good idea to have one day between Sunday and election day, making Tuesday the preferred day over Monday.

But even during this period there remained elements of an election season. According to Scott James[11], the 1848 congressional elections spanned 15 months, from August 1848 to November 1849. Leading up to the Civil War, a clear split in scheduling congressional elections emerged.

Northern states tended to adopt the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, the same day as presidential elections, to hold congressional elections. Southern states, in contrast, scheduled congressional elections several months after presidential election day. It wasn’t until 1872 that Congress mandated that all states hold their congressional elections on the same day as the presidential election.

Moreover, a state’s early statewide electoral contests could act as a political laboratory for national elections. The saying “As Maine goes, so goes the nation[12]” originated in the 19th century as Maine’s early statewide election returns, particularly in the governor’s race, often predicted the party of the presidential election winner. Political parties converged on Maine in September to rally their voters in hopes of influencing the November presidential election across the nation.

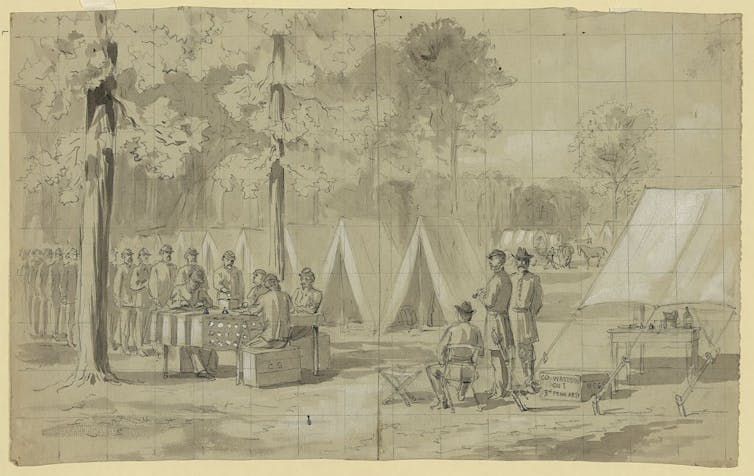

The establishment of an explicit early voting period rests on the precedent set during the Civil War[13]. There were numerous ways soldiers on the battlefield could cast their vote: mailing proxy votes, ballots or voting in person at camps and hospitals close to the battlefield.

The proxy votes, ballots, and/or tally sheets from the voting sites were then mailed to the soldier’s or sailor’s home state for counting. In Ohio, the absentee military ballots that were considered qualified – from white men over 21 years old – accounted for 12%[14] of Ohio’s votes in the 1864 presidential election.

Since then, multiple forms of early voting have been established. Early voting can happen in person or through voting by mail. In a 2001 federal appeals case[15] challenging Oregon’s no-excuse absentee voting, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld early voting periods, ruling that the election must only be “consummated” on Election Day.

In other words, voters need to cast their ballots by Election Day, but the law does not prevent them from voting earlier.

Union soldiers from Pennsylvania voting at their encampment in the presidential election, Army of the James, 1864.

William Waud/Library of Congress[16]

Union soldiers from Pennsylvania voting at their encampment in the presidential election, Army of the James, 1864.

William Waud/Library of Congress[16]

Early voting accelerates

In 1978, California lifted the requirement that a voter provide an approved reason, such as “occupation requiring travel or federal or state military or naval service[17],” to vote by mail, initiating a trend of early voting by mail in several Western states.

In the 1980s, Texas offered its voters early voting in person. The number of states adopting early voting periods[18] began to surge in the 1990s and included Florida, Nevada, Georgia, Tennessee and Iowa. After the 2000 presidential election and the controversy over “hanging chads,” many more states adopted early in-person voting periods to help with election administration.

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission[19] reports that in 2016 more than 41% of all ballots nationwide were cast before Election Day – with in-person early voting making up 17%, and voting by mail 24%, of all turnout.

Early voting is on its way to break all records in 2020, because of the pandemic, expansion of mail-in voting and voter interest. As of Oct. 7, Michael McDonald of the U.S. Elections Project[20] reports that over 5 million voters have already cast their ballots, compared with approximately 75,000 voters in 2016[21].

Does early voting increase voter turnout rates overall, or does it just split the voters who would normally vote on Election Day?

While some scholars contend that early in-person voting periods potentially can decrease[22] voter turnout, studies that focus on vote-by-mail, a form of early voting, generally show an increase [23]in voter turnout. New research[24] presents evidence that the implementation of all-mail voting in Colorado increased voter turnout by 9.4 percent overall.

Early voting periods may have an effect on who turns out, as well – which may explain Attorney General Barr’s lack of enthusiasm for early voting periods. Although past studies[25] have shown that early voting did not help one party over the other, the 2020 election may be different.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter[26].]

As of early October 2020[27], Democrats have cast 55.3% of the early ballots, whereas Republicans have cast only 24.2%. Independents have cast 19.8% and voters affiliated with a minor party less than 1%.

But there is still plenty of time for more people to vote early, either by mail or in person, before Election Day.

References

- ^ having begun more than six weeks before Election Day (www.wgbh.org)

- ^ we’re losing the whole idea of what an election is (slate.com)

- ^ Artist, Frederic B. Schell/Free Library of Philadelphia (libwww.freelibrary.org)

- ^ The first presidential election (www.mountvernon.org)

- ^ 1792, Congress passed a law (www.loc.gov)

- ^ From 1789 to 1840 (www.jstor.org)

- ^ PhotoQuest/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ 1840 presidential electoral season (kansaspress.ku.edu)

- ^ Congress formally adopted a national election day (www.loc.gov)

- ^ the importation of voters from one State to another.” (memory.loc.gov)

- ^ Scott James (doi.org)

- ^ As Maine goes, so goes the nation (www.jstor.org)

- ^ precedent set during the Civil War (postalmuseum.si.edu)

- ^ accounted for 12% (postalmuseum.si.edu)

- ^ 2001 federal appeals case (caselaw.findlaw.com)

- ^ William Waud/Library of Congress (lccn.loc.gov)

- ^ occupation requiring travel or federal or state military or naval service (calmatters.org)

- ^ states adopting early voting periods (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ U.S. Election Assistance Commission (www.eac.gov)

- ^ Michael McDonald of the U.S. Elections Project (electproject.github.io)

- ^ approximately 75,000 voters in 2016 (www.reuters.com)

- ^ decrease (www.jstor.org)

- ^ increase (doi.org)

- ^ New research (uc72f23077aa90e9f37223ab4213.dl.dropboxusercontent.com)

- ^ past studies (siepr.stanford.edu)

- ^ Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ As of early October 2020 (electproject.github.io)

Authors: Terri Bimes, Associate Teaching Professor of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley